- Search

Abstract

Purpose

Obtaining a detailed family history through detailed pedigree is essential in recognizing hereditary colorectal cancer (CRC) syndromes. This study was performed to assess the current knowledge and practice patterns of surgery residents regarding familial risk of CRC.

Methods

A questionnaire survey was performed to evaluate the knowledge and the level of recognition for analyses of family histories and hereditary CRC syndromes in 62 residents of the Department of Surgery, Seoul National University Hospital. The questionnaire consisted of 22 questions regarding practice patterns for, knowledge of, and resident education about hereditary CRC syndromes.

Results

Two-thirds of the residents answered that family history should be investigated at the first interview, but only 37% of them actually obtained pedigree detailed family history at the very beginning in actual clinical practice. Three-quarters of the residents answered that the quality of family history they obtained was poor. Most of them could diagnose hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer and recommend an appropriate colonoscopy surveillance schedule; however, only 19% knew that cancer surveillance guidelines differed according to the family history. Most of our residents lacked knowledge of cancer genetics, such as causative genes, and diagnostic methods, including microsatellite instability test, and indicated a desire and need for more education regarding hereditary cancer and genetic testing during residency.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that surgical residents' knowledge of hereditary cancer was not sufficient and that the quality of the family histories obtained in current practice has to be improved. More information regarding hereditary cancer should be considered in education programs for surgery residents.

Colorectal cancer (CRC), which is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in Korea [1], exhibits familial clustering in up to 20-30% of all cases [2-4]. As many as 5% of them are associated with familial genetic syndromes, such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, juvenile polyposis syndrome and MYH-associated polyposis [5]. HNPCC is the most common form of hereditary colorectal cancer, accounting for 2-5% of all CRCs with a prevalence of 1/2,000 [6]. HNPCC is basically diagnosed by obtaining a detailed family history from index CRC patient.

CRC is one of the most steeply increasing malignancies in Korea [1]; this increase also makes it more important to recognize a hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome. Diagnosis of hereditary CRC is based on family history and various clinicopathologic characteristics. Detecting hereditary CRC not only enables appropriate management of patients with hereditary CRC, but allows high-risk individuals among the family members to be identified and standard cancer surveillance to be recommended for them, thus preventing advanced hereditary CRC syndrome-associated malignancies in affected familial members. Currently, genetic testing for a causative gene, including the APC gene for FAP and the mismatch repair gene (MMR) for HNPCC, in common hereditary CRC is commercially available. However, suspicion by the clinician up front is still an essential prerequisite for the diagnosis of hereditary CRC syndromes [5]. Therefore, healthcare providers should keep in mind that the family history should be thoroughly scrutinized in all CRC patients.

In most large hospital in Korea, surgery residents are educated in the management of inpatients during their residency. They interview patients on admission, perform preoperative examinations, provide postoperative care, counsel patients and their families, and explain therapeutic plans. Thus, they should play a key role in obtaining a detailed family history, which would be the basis for diagnosing hereditary CRC syndrome. Several reports from Western countries have suggested that even physicians, not to mention residents, lacked knowledge about screening, diagnosing and managing hereditary CRC syndromes [4, 7-10]. Regarding residents, very little information exists about residents' knowledge of and current practices for hereditary cancer syndromes; moreover, education programs to improve knowledge of hereditary cancer and cancer genetics are lacking. Therefore, we designed this study to assess in our surgery residents current practices for documenting family history, as well as knowledge of and education for hereditary CRC syndromes.

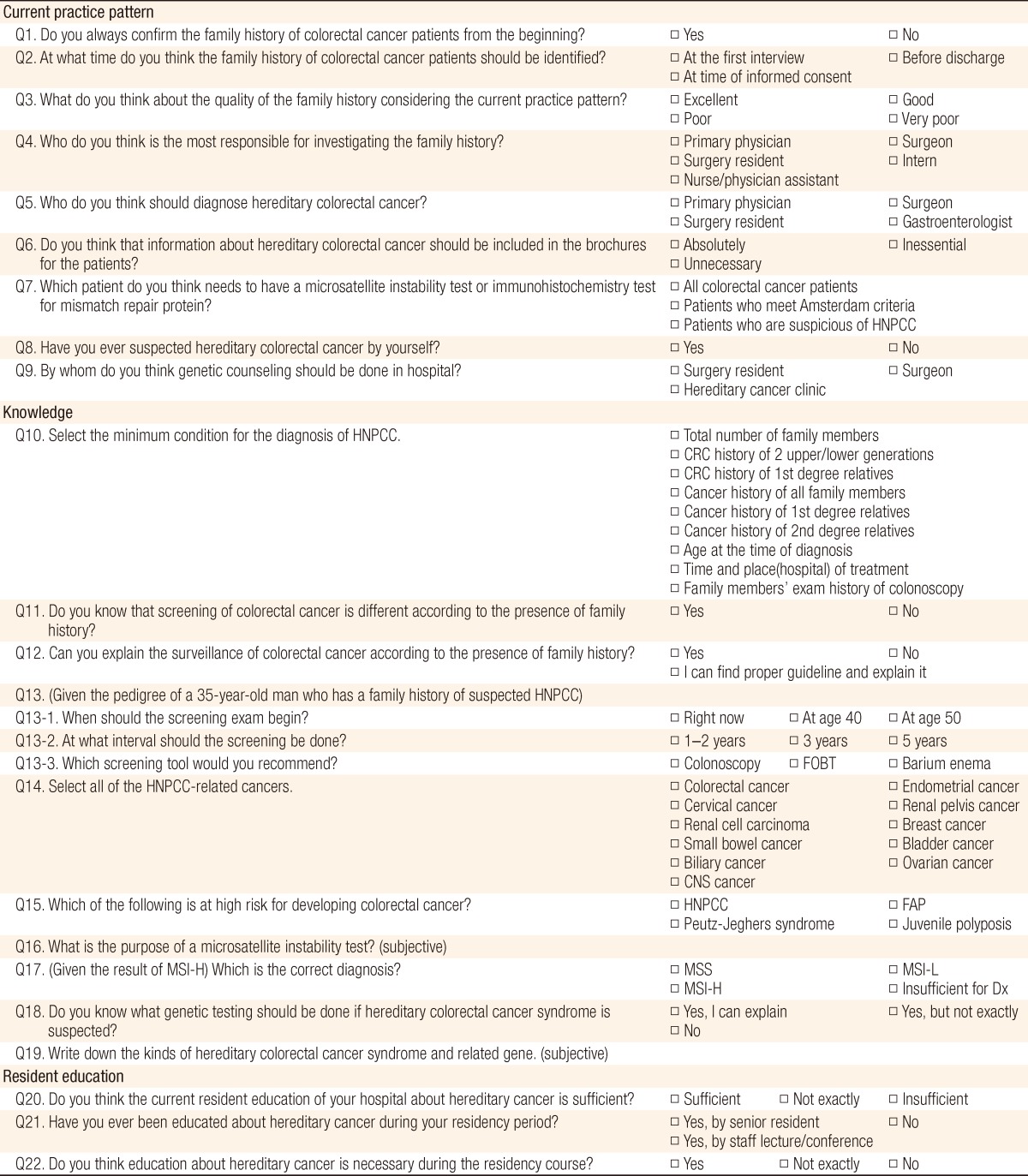

We conducted a questionnaire survey targeting 62 residents of our department, the Department of Surgery, Seoul National University Hospital. The questionnaire used in this study consisted of twenty-two questions addressing the following topics: 1) current practice of obtaining and interpreting a family history (Q1, 2), the quality of the family history currently obtained (Q3), the responsibility for the investigation and the diagnosis of hereditary CRC syndromes (Q4, 5, 8), patient education and counseling (Q6, 9) and the necessity for a microsatellite instability (MSI) test (Q7); 2) residents' knowledge on how to obtain an accurate family history (Q10), diagnosis, surveillance programs, causative genes and cancer risk of hereditary CRC syndromes (Q11-15, 18, 19), and MSI testing (Q16 ,17); 3) current resident's education on hereditary cancer syndromes (Q20-22) (Table 1). The questionnaire used in this study was an adapted and modified version of those used in previous studies that studied obstetrics/gynecology residents' and physicians' knowledge regarding hereditary cancer syndromes [8-10].

Data from the submitted questionnaire were analyzed using ANOVA for comparing scores. P-values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed by using IBM SPSS ver. 18.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

Of the 62 surgery residents, there were 9 (14.5%) in the 1st year, 17 (27.4%) in the 2nd and 3rd years, and 19 (30.6%) in the 4th year. Seventeen residents (27.4%) were women. All participating residents answered the questionnaire completely.

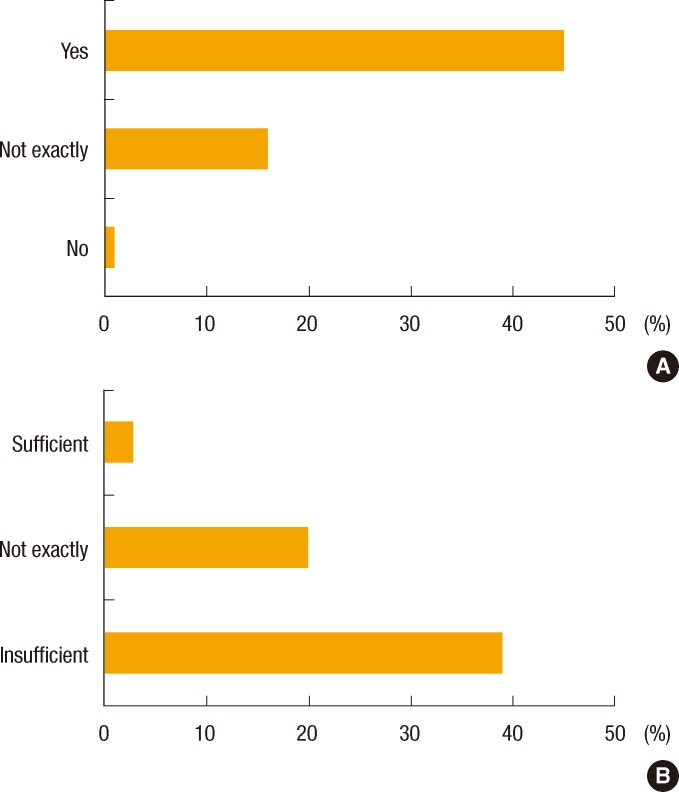

About two-thirds of the residents (66.1%) answered that family history should be identified at the first interview; however, only 23 (37.1%) responded that they investigated the family history of a CRC patient at admission. For the question asking who is responsible for obtaining the family history, over half (53.2%) replied that nurses and physician assistants had more responsibility than either primary physicians (14.5%) or surgery residents (21.0%). A majority of respondents answered that the quality of the family histories that they now obtained needed to be improved (75.8%) (Fig. 1). Half of the surgery residents (51.6%) had suspected hereditary CRC syndrome by themselves. Twenty-nine of the residents (46.8%) thought that the surgeon had responsibility for the diagnosis of hereditary CRC syndrome. According to 33.9% of the residents, MSI testing or immunohistochemistry examination should be performed in only patients who meet the Amsterdam criteria, and 56.5% answered that patients suspected of having hereditary CRC need to have immunohistochemistry (IHC) of the MMR protein. Only 6 (9.7%) thought all CRC patients should receive MSI testing or IHC of the MMR protein (Fig. 2). Most (79.0%) answered genetic counseling should be done in a separate hereditary cancer clinic, not in the hospital. Forty-eight residents (77.4%) replied that information on hereditary CRC should be included in hospital brochures for patients with CRC.

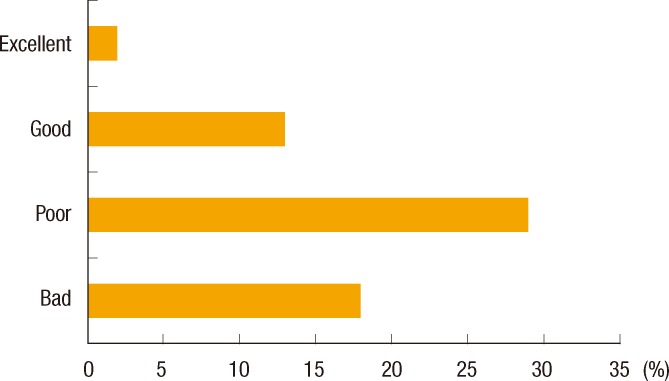

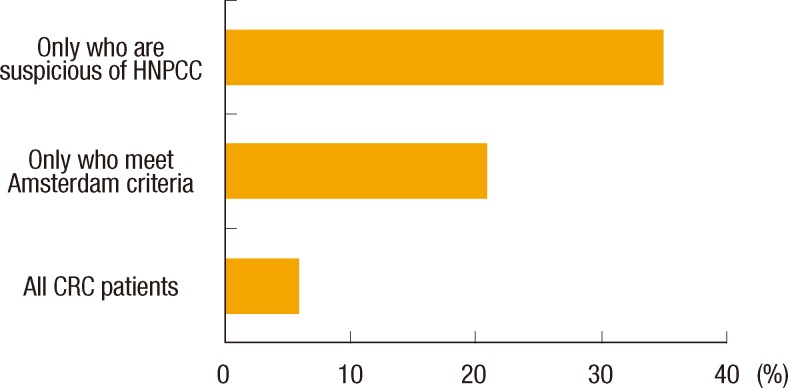

Most residents (87.1%) knew that screening for CRC differs according to the presence and intensity of the family history. Of the residents, 79.0% and 83.9% showed correct answers to the questions on the beginning and the interval, respectively, of screening for HNPCC-associated malignancies. Only 19.4% knew the detailed surveillance guidelines. Correct knowledge about the diagnostic criteria for HNPCC was found in only 57.9% of the residents. For questions on the clinical characteristics of HNPCC, most residents correctly recognized CRC and endometrial cancer as HNPCC-associated cancer (96.8% and 87.1%, respectively), but 72.6% did not recognize renal pelvis cancer and small bowel cancer as HNPCC-associated cancers. On the other hand, 37 of the respondents (59.7%) mistook ovary cancer as an HNPCC-related cancer (Fig. 3). The overall accurate response rate on HNPCC-related cancers was 71.2% and was not different for different years of residency (P = 0.420). For the question on the diagnostic methods for HNPCC, 17.7% understood the purpose of MSI completely, and only 22.6% appropriately interpreted the MSI status. Only a bit over 10% of the residents (11.3%) correctly matched specific hereditary colon cancer syndrome and its causative gene.

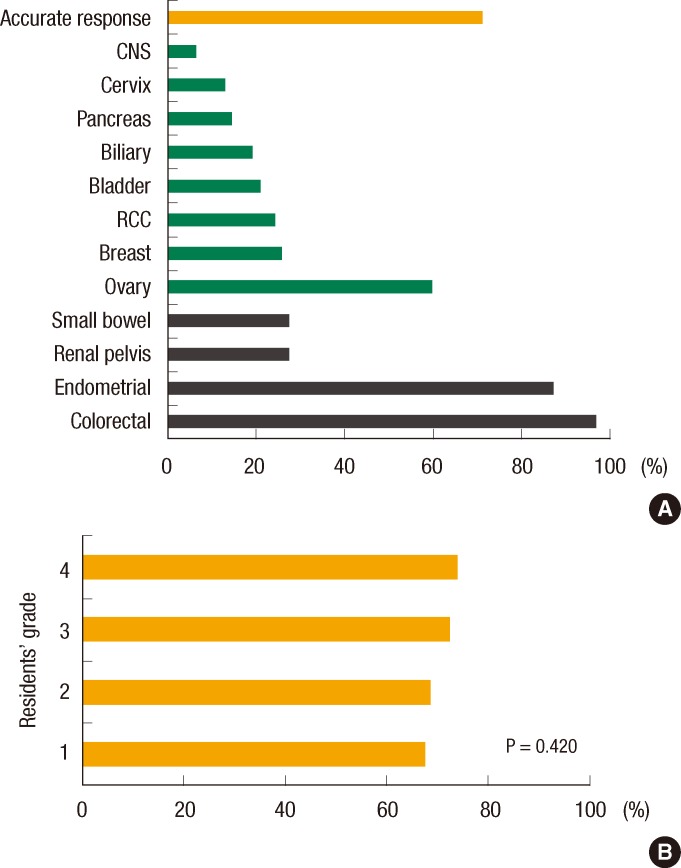

Above 70% of the respondents (72.6%) answered that it is vital to be educated about hereditary cancer during their residency courses. Among the 62.9% of the residents who responded that they had been educated about hereditary cancer, 41.9% had learned about it from staff lectures and 21.0% had picked it up by chance from senior residents. Almost all respondents (95.2%) replied that the current education about hereditary cancer is not sufficient (Fig. 4).

Although this investigation was performed with the participation of surgery residents in one large third-referral hospital, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to evaluate current-practice patterns, levels of recognition and knowledge about family history and hereditary CRC syndrome in Korean surgical residents. The results are similar to those of previous studies to some extent, but not quite the same. The rates of routinely obtaining family histories varied widely among previous studies, ranging from 35% to 90% [4, 9]. Stoner et al. [10] reported 27% of pediatric residents inquired about family history in early-onset CRC patients. In our study, 37.1% of surgery residents actually obtained the family history at the very beginning. Interestingly, this result was in conflict with the finding that 66.1% of the residents thought that the family history should be collected at the first interview. This gap between thought and real practice seems to be associated with the lack of awareness on the residents' part that they themselves are mainly responsible for investigating the family histories of patients they are taking care of. A large portion of the residents answered that collecting the family history is the role of the nurse and the physician assistant (53.2%) or the primary physician (14.5%). Many of them also answered that they were not primarily responsible for counseling on hereditary CRC. Genetic counseling, including investigation of family history, education of patients and family members, and consultation on the psychosocial aspects [11], should be performed by professionally-trained genetic counselors. However, considering the fact that there are few genetic counseling specialists for hereditary CRC syndrome in most hospitals in Korea, even third-referral hospitals, the tough reality is that surgery residents should also play the role of genetic counselor to some extent.

Even if the family history of CRC is obtained at the first interview, hereditary CRC syndromes can be missed when the collected history does not contain all the necessary information for their diagnosis. In order to increase the chance of detecting affected family members, as a minimum, a three-generation family history should be obtained, and detailed family history of not only CRC but also colon polyps and extracolonic cancers, with the age of diagnosis, should be included [2]. However, this is not currently well done in many cases. Over three-fourths of surgery residents (75.8%) thought that the qualities of the collected family histories were either poor (46.8%) or bad (29.0%). Furthermore, only 57.9% was the accurate response rate of the minimum condition for diagnosing HNPCC, which means they do not exactly know what information should be included requisitely. These results may reflect a deficiency in appropriate education about hereditary CRC.

Screening and surveillance for CRC is different according to the risk that each individual has. For example, patients with a family history of either CRC or adenomatous polyps in a first-degree relative before age 60 years should undergo colonoscopy at age 40 years, which is 10 years earlier than those who do not have such a family history [12]. Most surgery residents knew that screening for CRC differed according to the family history, and a number of them correctly answered the questions about the beginning and the interval of screening for suspected HNPCC. Nevertheless, only 19.4% of residents responded that they could explain the surveillance recommendations for CRC exactly. A possible reason is that they seldom provide counsel about hereditary cancer syndrome in actual practice. Furthermore, although over 70% of the respondents accurately identified HNPCC-associated cancers, only 27.4% of the respondents chose renal pelvis cancer and small bowel cancer. On the other hand, about 60% of them selected ovarian cancer as a HNPCC-related cancer. This was similar to the result of a previous study, which reported obstetrics/gynecology residents correctly knew that CRC and endometrial cancer were HNPCC-related cancers (92% and 63%, respectively), but 52% of them mistook ovarian cancer as a HNPCC-associated cancer [9]. According to the revised International Collaborative Group on HNPCC criteria (Amsterdam criteria II), HNPCC-associated cancers are CRC and cancers of the endometrium, small bowel, ureter and renal pelvis [13]. Although the lifetime risk of ovarian cancer is as high as 10-12% in HNPCC patients [14, 15], it is still not included in the diagnostic criteria of HNPCC. Educating surgery residents, who are participating in preoperative workups for CRC, about the diagnosis of HNPCC is essential, given the possible change of treatment plan to a total colectomy or a prophylactic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy [16].

Our surgery residents in this study seemed unfamiliar with the details of genetic testing, MSI testing and immunohistochemistry for MMR proteins, including the indications, the interpretation of results, and the risk evaluation for an individual based on the test results. Few surgery residents knew the purpose of MSI testing and could interpret its result correctly. MSI testing is useful not only in recognizing HNPCC but also in finding sporadic HNPCC without familial predisposition from parents. Sturgeon et al. [17] reported only 34% of patients were found to have an MMR mutation based on family history alone. Therefore, MSI testing can be used to recognize suspected HNPCC patients who do not meet the Amsterdam criteria, leading them to have subsequent gene sequencing [18]. The revised Bethesda guidelines suggest this broader set of guidelines to select cases for MSI testing [19]. In addition, some authors even assert that MSI testing should be performed on all new colorectal cancers to improve identification of HNPCC [20]. Our institute, Seoul National University Hospital, has also routinely performed MSI testing for all colorectal cancers since 2007. Furthermore, MSI testing is used in identifying MSI-high sporadic CRCs. MSI-high CRCs have been reported to have different clinical and pathologic characteristics [21, 22]. MSI-high tumors are known to have more favorable stage-adjusted prognosis than MSI-low or microsatellite stable tumors [22]. Thus, information on MSI status is important for determining whether or not chemotherapy should be provided to stage-II colon cancer patients [21]. In addition, our residents should be taught that MSI testing is important for the accurate diagnosis and the proper management of colorectal cancer is important.

Most of the residents in this study thought that current education about hereditary cancer syndromes via staff lectures or senior residents was insufficient. The results for residents' knowledge about family history and hereditary cancer syndromes, as described above, seem to suggest that current education is not systematic. That may be a possible reason that the correct response rates did not increase as the residents advanced through their training. Ready et al. [9] reported that 76% of obstetrics/gynecology residents wanted more information and education about hereditary cancer and genetic testing. Likewise, our residents desired a more intensified education program that would fulfill their requirements for more information about hereditary cancer syndromes.

In summary, the present study indicated that the quality of at the family history in current practice has to be improved and that surgical residents' knowledge about hereditary cancer is not sufficient. Education programs for surgery residents should consider their need for more information regarding hereditary cancer and genetic testing.

References

1. Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Oh CM, Seo HG, Lee JS. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence in 2010. Cancer Res Treat 2013;45:1ŌĆō14. PMID: 23613665.

2. Kaz AM, Brentnall TA. Genetic testing for colon cancer. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;3:670ŌĆō679. PMID: 17130877.

3. Lynch HT, de la Chapelle A. Genetic susceptibility to non-polyposis colorectal cancer. J Med Genet 1999;36:801ŌĆō818. PMID: 10544223.

4. Barrison AF, Smith C, Oviedo J, Heeren T, Schroy PC 3rd. Colorectal cancer screening and familial risk: a survey of internal medicine residents' knowledge and practice patterns. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:1410ŌĆō1416. PMID: 12818289.

5. Gala M, Chung DC. Hereditary colon cancer syndromes. Semin Oncol 2011;38:490ŌĆō499. PMID: 21810508.

7. Batra S, Valdimarsdottir H, McGovern M, Itzkowitz S, Brown K. Awareness of genetic testing for colorectal cancer predisposition among specialists in gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:729ŌĆō733. PMID: 11922570.

8. Schroy PC 3rd, Barrison AF, Ling BS, Wilson S, Geller AC. Family history and colorectal cancer screening: a survey of physician knowledge and practice patterns. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:1031ŌĆō1036. PMID: 12008667.

9. Ready KJ, Daniels MS, Sun CC, Peterson SK, Northrup H, Lu KH. Obstetrics/gynecology residents' knowledge of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer and Lynch syndrome. J Cancer Educ 2010;25:401ŌĆō404. PMID: 20186516.

10. Stoner J, Qi Y, Erdman SH, Attard TM. A web-based assessment of pediatrics resident medical knowledge in childhood hereditary gastrointestinal cancer predisposing syndromes. J Cancer Educ 2009;24:254ŌĆō256. PMID: 19838880.

11. Trimbath JD, Giardiello FM. Review article: genetic testing and counselling for hereditary colorectal cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;16:1843ŌĆō1857. PMID: 12390093.

12. Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Smith RA, Brooks D, Andrews KS, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin 2008;58:130ŌĆō160. PMID: 18322143.

13. Vasen HF, Watson P, Mecklin JP, Lynch HT. New clinical criteria for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC, Lynch syndrome) proposed by the International Collaborative group on HNPCC. Gastroenterology 1999;116:1453ŌĆō1456. PMID: 10348829.

14. Aarnio M, Sankila R, Pukkala E, Salovaara R, Aaltonen LA, de la Chapelle A, et al. Cancer risk in mutation carriers of DNA-mismatch-repair genes. Int J Cancer 1999;81:214ŌĆō218. PMID: 10188721.

15. Dunlop MG, Farrington SM, Carothers AD, Wyllie AH, Sharp L, Burn J, et al. Cancer risk associated with germline DNA mismatch repair gene mutations. Hum Mol Genet 1997;6:105ŌĆō110. PMID: 9002677.

16. Schmeler KM, Lynch HT, Chen LM, Munsell MF, Soliman PT, Clark MB, et al. Prophylactic surgery to reduce the risk of gynecologic cancers in the Lynch syndrome. N Engl J Med 2006;354:261ŌĆō269. PMID: 16421367.

17. Sturgeon D, McCutcheon T, Geiger TM, Muldoon RL, Herline AJ, Wise PE. Increasing Lynch syndrome identification through establishment of a hereditary colorectal cancer registry. Dis Colon Rectum 2013;56:308ŌĆō314. PMID: 23392144.

18. Oh JR, Kim DW, Lee HS, Lee HE, Lee SM, Jang JH, et al. Microsatellite instability testing in Korean patients with colorectal cancer. Fam Cancer 2012;11:459ŌĆō466. PMID: 22669410.

19. Umar A, Boland CR, Terdiman JP, Syngal S, de la Chapelle A, Ruschoff J, et al. Revised Bethesda Guidelines for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) and microsatellite instability. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004;96:261ŌĆō268. PMID: 14970275.

20. Vasen HF, Moslein G, Alonso A, Aretz S, Bernstein I, Bertario L, et al. Recommendations to improve identification of hereditary and familial colorectal cancer in Europe. Fam Cancer 2010;9:109ŌĆō115. PMID: 19763885.

21. Sargent DJ, Marsoni S, Monges G, Thibodeau SN, Labianca R, Hamilton SR, et al. Defective mismatch repair as a predictive marker for lack of efficacy of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3219ŌĆō3226. PMID: 20498393.

22. Popat S, Hubner R, Houlston RS. Systematic review of microsatellite instability and colorectal cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:609ŌĆō618. PMID: 15659508.

Fig.┬Ā2

Surgery residents' opinions about the necessity of a microsatellite instability test. HNPCC, hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer; CRC, colorectal cancer.

Fig.┬Ā3

(A) Surgery residents' response rates of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer-associated cancer. Correct answers are colorectal, endometrial, renal pelvis and small bowel. (B) Accurate response rate according to residents' grades. CNS, central nervous system; RCC, renal cell carcinoma.

Fig.┬Ā4

Surgery residents' thoughts regarding the necessity of education about hereditary cancers (A) and the sufficiency of current education (B).