- Search

Abstract

Purpose

A rectourethral fistula (RUF) is an uncommon complication resulting from surgery, radiation or trauma. Although various surgical procedures for the treatment of an RUF have been described, none has gained acceptance as the procedure of choice. The aim of this study was to review our experience with surgical management of RUF.

Methods

The outcomes of 6 male patients (mean age, 51 years) with an RUF who were operated on by a single surgeon between May 2005 and July 2012 were assessed.

Results

The causes of the RUF were iatrogenic in four cases (two after radiation therapy for rectal cancer, one after brachytherapy for prostate cancer, and one after surgery for a bladder stone) and traumatic in two cases. Fecal diversion was the initial treatment in five patients. In one patient, fecal diversion was performed simultaneously with definitive repair. Four patients underwent staged repair after a mean of 12 months. Rectal advancement flaps were done for simple, small fistula (n = 2), and flap interpositions (gracilis muscle flap, n = 2; omental flap, n = 1) were done for complex or recurrent fistulae. Urinary strictures and incontinence were observed in patients after gracilis muscle flap interposition, but they were resolved with simple treatments. The mean follow-up period was 28 months, and closure of the fistula was achieved in all five patients (100%) who underwent definitive repairs. The fistula persisted in one patient who refused further definitive surgery after receiving only a fecal diversion.

A rectourethral fistula (RUF) is an uncommon complication that is mostly iatrogenic in origin, but can also be caused by a neoplasm, infection, inflammation or trauma. Iatrogenic RUF are often the results of surgery or irradiation for prostate cancer, and less commonly are the result of rectal cancer [1]. With the increase in the types of multimodal treatments, including surgery, radiation therapy or brachytherapy, for prostate cancer, the incidence of iatrogenic RUF has also been increasing. The incidence of RUF is known to be approximately 0.1%-3% in patients who received these therapies [2].

Treatment of RUF is still challenging due to the rarity and complexity of this condition. In some small RUF, spontaneous closure can be expected with fecal and urinary diversion. Because such an outcome is rare, surgical repair is definitely required for most RUF [3]. Numerous surgical techniques, including transanal, transsphincteric, transperineal and transabdominal approaches, based on a surgeon's preference have been described [4-8]. However, although varying outcomes have been reported in many studies, to date, no treatment method has gained general acceptance as a standardized treatment of choice. Although RUF have a urologic origin in many cases, their treatment often requires judgment and assistance from colorectal surgeons. In this study, we analyzed the outcomes of various procedures for the surgical treatment of RUF.

During the period between May 2005 and July 2012, six consecutive patients underwent an operation for a RUF by a single colorectal surgeon. They were registered prospectively and reviewed retrospectively. This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board (No. 1310-014-524).

Electronic medical records were assessed, and the data on patients' demographics, clinical presentations, past medical histories, previous histories of operations, locations of the fistula including the distance from anal verge, sizes of the fistulae, times to fistula development, operative procedures, times of fistula repair, and acute and chronic complications were included. The etiology of the RUF was defined with an evaluation of the history of previous treatments or trauma. The fistula was diagnosed by using the suspected symptoms of a urinary fistula and by directly visualizing the fistula with cystoscopy, colonoscopy or radiographic studies with fistulography. Supplementary investigations, such as computed tomography (CT) scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), were done to understand the anatomy of the fistula and that of the surrounding structures (Fig. 1).

Six male patients were identified. The RUF had an iatrogenic origin in 4 patients (66.7%) and traumatic origin in the other 2 patients (33.3%). Two patients had a fistula resulting from radiation therapy after surgery for rectal cancer. We performed rectal cancer surgery in 1,882 patients during the same period and combined radiation therapy in 304 patients. Thus, the incidence of an RUF in patients who underwent radiation therapy for rectal cancer was 0.7%. For the treatment of the fistula, four patients were referred to our hospital from other hospitals. Presented complaints were usually a combination of urine passage through the rectum, fecaluria and pneumaturia. Bleeding was observed in one patient with a radiation-induced ulcer in the area of the fistula. The clinical characteristics of the six patients are described in Table 1.

The principle of identifying and excising the fistula and closing the opening after careful debridement of granulation tissue remains the same in different surgical techniques. Rectal advancement flap repairs are typically performed in the Jack-knife prone position under spinal or general anesthesia. A partial thickness flap including the internal sphincter is prepared in a reverse trapezoidal shape with a broad proximal base. After identification of the fistula, a submucosal dissection around the tract and removal of the tract is done. The opening on the rectal side is closed with a primary suture, and the flap is advanced down. The urethral opening remains open for drainage. Gracilis muscle flap interpositions are performed in the lithotomy position. After a 5 cm curvilinear incision is made in the perineum, a dissection into the plane between the rectum and the urethra is done until noninflamed tissue over the fistula is reached. The fistula tract is then identified and excised. The fistula opening on the rectal side is either closed primarily or with a rectal advancement flap whereas closure of the fistula opening on the urethral side is done by a urologist. The gracilis muscle is harvested from the inner part of the thigh and is disconnected from its insertion near the tibial condyle. Through the subcutaneous tunnel made towards the perineum, the muscle is rotated so as to be placed in the perineum and is sutured to the anterior side of the rectum (Fig. 2). An omental flap interposition is performed with a laparotomy incision. The omentum is dissected from the right to the left side, preserving the left gastroepiploic artery in the pedicle. The flap is placed between the rectum and the urethra after pelvic dissection and is followed by a fistulectomy (Fig. 3). Successful closure is defined as the absence of RUF symptoms, such as urinary tract infection, pneumaturia, fecaluria, or passage of urine through the rectum concurrently with the absence of the fistula on cystoscopy, colonoscopy or radiographic studies with fistulography.

Stoma formation for fecal diversion was the initial treatment in five patients. In the remaining patient, stoma formation was done simultaneously with a definitive RUF repair. A cystostomy for urinary diversion was done in three patients. Four patients underwent a staged repair after a mean of 12.0 months (range, 8 to 15 months). A rectal advancement flap was used for simple, small fistulae (n=2), and flap interpositions (gracilis muscle, n=2; omental flap, n=1) were used for complex or recurrent fistulae. In one patient, a simple primary closure of the RUF and a urethroplasty for urinary stricture were initially performed by a urologic surgeon. However, because the fistula persisted, a rectal advancement flap was performed as a definitive repair. Another patient who had a simple, low-lying fistula underwent a rectal advancement flap. Gracilis muscle flap interpositions were performed in one patient who had a recurrent RUF after undergoing a rectal advancement flap twice at other hospitals, and the other who had a huge fistula located high at the level of the bladder neck. An omental flap interposition was performed in a patient who required an explorative laparotomy due to coexisting intra-abdominal injuries resulting from a traffic accident. The remaining patient declined to have further treatments even though a definite repair had been recommended (Fig. 4).

No complications were associated with a rectal advancement flap. Urinary strictures developed in two patients after gracilis muscle flap interpositions, but they resolved easily with an endoscopic internal urethrotomy. Also, urinary incontinence that resulted from a prostatectomy was observed in one patient with gracilis muscle flap interposition, but it resolved at once with a transurethral injection. An intra-abdominal abscess developed in the patient with an omental flap interposition.

The mean length of hospital stay in this study was 15 days (range, 6 to 28 days). Closure of the fistula was achieved and was maintained for a mean follow-up of 28.0 months (range, 15 to 52 months) in all five patients (100%) who underwent definitive repairs. However, the fistula persisted in the one patient who underwent only a fecal diversion. Stoma take-down was performed in 4 patients after a mean follow-up of 15.0 months (range, 6 to 17 months). In the remaining two patients, the stomas were kept from take down because one patient had metastasis and recurrence of previous rectal cancer and the other refused to have further treatments. The surgical outcomes of the RUF repairs in the six patients are described in Table 2.

An RUF is a rare, but distressing, complication for both the patients and the surgeons. Since an RUF is challenging to treat and may seriously impact the quality of life of the patients, optimal treatment plans should be made to minimize morbidities. Most studies advocate fecal and urinary diversion as the initial treatment in the management of an RUF because diversion may provide better conditions to safely dissect the plane between the rectum and the urethra by controlling the local inflammation and contamination around the fistula [9]. However, the spontaneous closure rate for RUF after diversion only has been reported to be 14% to 46.5% [10, 11], implying that a staged and definitive surgical treatment is necessary in the majority of the patients. This was obviously shown in our study because during a mean 12 months observational period, no spontaneous closures were observed in patients who underwent only a diversion. Furthermore, in a patient who declined to undergo a definitive repair, 37 months of conservative management after a sole diversion was insufficient to heal the RUF.

The presence of fecaluria in an RUF is known to be a poor prognostic sign, indicating that the fistula may be large in size [12]. Interestingly, all of our patients showed fecaluria, and this might partially explain why they needed further definitive repairs. Other factors also known to be associated with poorer outcomes are large fistula size (>2 cm), as well as radiation and cryotherapy [13, 14]. Radiation may lead to microvascular injuries and mucosal ischemia, which are susceptible to fistula formation. Moreover, as recently reported, up to 50% of RUF patients have a history of irradiation [15]. In most of our patients with RUF, the RUF had an iatrogenic origin and were associated with radiation therapy for cancer treatment, and the clinical courses of those patients were more complex during the treatment period.

The transanal approach with rectal advancement flap can be utilized in small, low-lying RUF and is safe and effective in the absence of prior radiation therapy. Though the reported closure rate with this approach is the lowest among the transperineal, transabdominal and transsphincteric approaches [2], that result is for only a very small number of cases. One study reported an 83% closure rate with a transanal rectal advancement flap in 12 patients and suggested that this procedure might be effective and provide obvious advantages, such as minimal postoperative pain, rapid recovery, and the feasibility of performing further procedures when required [16]. A rectal advancement flap has been used more frequently and is considered to be an effective procedure for treating anorectal or rectovaginal fistulae where the rectum is the high-pressure side [17, 18]. However, in RUF, because the urethra is the high-pressure side, the transanal approach should be limited to small, simple fistulae whereas a large fistula might require a more complex procedure [19].

We performed a rectal advancement flap in two patients. Successful closure was achieved in one patient who had a relatively simple RUF originating from a previous operation for bladder stones. In the other patient, a rectal advancement flap was planned, albeit that patient's irradiation history for rectal cancer, because the fistula was small and low-lying. Complete closure of the fistula was attained as well. Recently, less invasive procedures using bioglue to supplement poor visualization and instrumentalization of the transanal approach have also been described in some case reports [10], but the effectiveness of those procedures should be determined with further studies.

The transperineal approach with a gracilis muscle flap interposition is currently the most commonly used method and one of the effective procedures for treating complex fistulae. Low morbidity and high success rates have been reported with this approach in large, recurrent or irradiated RUF. In a recent systematic review, repair with this approach presented the highest closure rate, ranging up to 90% [2, 20]. In addition, associated urethral pathologies can be operated on at the same time through the transperineal route because it provides good exposure of the rectum, urethra and the neck of the bladder, thereby allowing distal urethral mobilization [21, 22]. Although morbidity after a gracilis muscle flap interposition is known to be low, urethral stricture and urinary incontinence can occur as complications. However, with further procedures to relieve these symptoms, satisfactory urinary and bowel functions have been achieved [9, 13]. Other vascularized tissue flaps, such as the dartos pedicle flap or the gluteus maximus flap can be used to pose a pressure barrier between the urethra and the rectum, and successful results have been reported [23, 24]. In our study, a gracilis muscle flap interposition was performed in two patients, one with a huge irradiated fistula and the other with a recurrent fistula. A radical retropubic prostatectomy was done simultaneously within the same transperineal excision in one of those patients. Urethral stricture and urinary incontinence were recognized after surgery, but they resolved with relatively simple urologic interventions without causing further complications.

The greater omentum was used via a transabdominal approach in a patient who required exploration of other possible coexisting injuries. This approach can be used in large RUF with severe radiation damage or with symptoms requiring extensive resections and permanent diversion, and successful results have been reported in some case series [2, 25]. However, a major laparotomy with a deep pelvic dissection is involved, and exposing the fistula site is difficult. As observed in our patient, severe adhesions due to a previous history of abdominal surgery is one of the main drawbacks that may lead to serious morbidity and lower closure rates [3, 22]. Eight days after the surgery, we encountered an intra-abdominal abscess in this patient, which was successfully treated with antibiotics and percutaneous drainage.

The York-Mason method, a posterior transsphincteric approach, was not performed in our study, but some have reported remarkable success with this approach [26]. Although the closure rate could reach as high as 88%, the use of this approach has decreased significantly recently because of the recognition of increasing fecal incontinence and fecal contamination, which can affect surgical outcomes. Although this approach allows access through the unscarred tissue and provides wide exposure of the fistula site, it is not be indicated in patients with fecal incontinence or severe radiation proctitis [2, 27]. Other procedures, such as the anterior approach or the Latzko technique, have also been introduced, but are not widely used [28, 29]. The comparative outcomes of various surgical procedures for RUF repair are described in Table 3.

This study has limitations due to its retrospective methodology and small number of cohorts. However, we experienced diverse patients and performed various types of repairs. The overall success rate was high, and the morbidity rate was low. A personalized approach and collaboration with urologists might have contributed to our favorable outcomes.

In conclusion, successful RUF closure can be achieved through individualized therapy based on the etiology, the severity, and the recurrence status of the RUF. A staged repair of the fistula is usually required to allow complete closure of the RUF. Relatively simple rectal advancement flap repairs can be used for small, low-lying, and less-complicated RUF whereas a gracilis muscle flap or an omental flap interposition can be used for irradiated, inflamed, large and recurrent RUF.

Notes

References

1. Nyam DC, Pemberton JH. Management of iatrogenic rectourethral fistula. Dis Colon Rectum 1999;42:994–997. PMID: 10458120.

2. Hechenbleikner EM, Buckley JC, Wick EC. Acquired rectourethral fistulas in adults: a systematic review of surgical repair techniques and outcomes. Dis Colon Rectum 2013;56:374–383. PMID: 23392154.

3. Bukowski TP, Chakrabarty A, Powell IJ, Frontera R, Perlmutter AD, Montie JE. Acquired rectourethral fistula: methods of repair. J Urol 1995;153(3 Pt 1): 730–733. PMID: 7861523.

4. Muñoz M, Nelson H, Harrington J, Tsiotos G, Devine R, Engen D. Management of acquired rectourinary fistulas: outcome according to cause. Dis Colon Rectum 1998;41:1230–1238. PMID: 9788385.

5. Parks AG, Motson RW. Peranal repair of rectoprostatic fistula. Br J Surg 1983;70:725–726. PMID: 6640253.

6. Kilpatrick FR, Mason AY. Post-operative recto-prostatic fistula. Br J Urol 1969;41:649–654. PMID: 5359484.

7. Miller W. A succesful repair of a recto-urethral fistula: a case report. Br J Surg 1977;64:869–871. PMID: 588985.

8. Ryan JA Jr, Beebe HG, Gibbons RP. Gracilis muscle flap for closure of rectourethral fistula. J Urol 1979;122:124–125. PMID: 458977.

9. Zmora O, Potenti FM, Wexner SD, Pikarsky AJ, Efron JE, Nogueras JJ, et al. Gracilis muscle transposition for iatrogenic rectourethral fistula. Ann Surg 2003;237:483–487. PMID: 12677143.

10. Lee TG, Park SS, Lee SJ. Treatment of a recurrent rectourethral fistula by using transanal rectal flap advancement and fibrin glue: a case report. J Korean Soc Coloproctol 2012;28:165–169. PMID: 22816061.

11. al-Ali M, Kashmoula D, Saoud IJ. Experience with 30 posttraumatic rectourethral fistulas: presentation of posterior transsphincteric anterior rectal wall advancement. J Urol 1997;158:421–424. PMID: 9224315.

12. Thomas C, Jones J, Jager W, Hampel C, Thuroff JW, Gillitzer R. Incidence, clinical symptoms and management of rectourethral fistulas after radical prostatectomy. J Urol 2010;183:608–612. PMID: 20018317.

13. Ghoniem G, Elmissiry M, Weiss E, Langford C, Abdelwahab H, Wexner S. Transperineal repair of complex rectourethral fistula using gracilis muscle flap interposition: can urinary and bowel functions be preserved? J Urol 2008;179:1882–1886. PMID: 18353391.

14. Chrouser KL, Leibovich BC, Sweat SD, Larson DW, Davis BJ, Tran NV, et al. Urinary fistulas following external radiation or permanent brachytherapy for the treatment of prostate cancer. J Urol 2005;173:1953–1957. PMID: 15879789.

15. Lane BR, Stein DE, Remzi FH, Strong SA, Fazio VW, Angermeier KW. Management of radiotherapy induced rectourethral fistula. J Urol 2006;175:1382–1387. PMID: 16516003.

16. Garofalo TE, Delaney CP, Jones SM, Remzi FH, Fazio VW. Rectal advancement flap repair of rectourethral fistula: a 20-year experience. Dis Colon Rectum 2003;46:762–769. PMID: 12794578.

17. Sonoda T, Hull T, Piedmonte MR, Fazio VW. Outcomes of primary repair of anorectal and rectovaginal fistulas using the endorectal advancement flap. Dis Colon Rectum 2002;45:1622–1628. PMID: 12473885.

18. Debeche-Adams TH, Bohl JL. Rectovaginal fistulas. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2010;23:99–103. PMID: 21629627.

19. Chun L, Abbas MA. Rectourethral fistula following laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Tech Coloproctol 2011;15:297–300. PMID: 21720888.

20. Wexner SD, Ruiz DE, Genua J, Nogueras JJ, Weiss EG, Zmora O. Gracilis muscle interposition for the treatment of rectourethral, rectovaginal, and pouch-vaginal fistulas: results in 53 patients. Ann Surg 2008;248:39–43. PMID: 18580205.

21. Vanni AJ, Buckley JC, Zinman LN. Management of surgical and radiation induced rectourethral fistulas with an interposition muscle flap and selective buccal mucosal onlay graft. J Urol 2010;184:2400–2404. PMID: 20952036.

22. Gupta G, Kumar S, Kekre NS, Gopalakrishnan G. Surgical management of rectourethral fistula. Urology 2008;71:267–271. PMID: 18308098.

23. Youssef AH, Fath-Alla M, El-Kassaby AW. Perineal subcutaneous dartos pedicled flap as a new technique for repairing urethrorectal fistula. J Urol 1999;161:1498–1500. PMID: 10210381.

24. Krand O, Unal E. Management of enema tip-induced rectourethral fistula with gluteus maximus flap: report of a case. Tech Coloproctol 2008;12:131–133. PMID: 18060353.

25. Moreira SG Jr, Seigne JD, Ordorica RC, Marcet J, Pow-Sang JM, Lockhart JL. Devastating complications after brachytherapy in the treatment of prostate adenocarcinoma. BJU Int 2004;93:31–35. PMID: 14678363.

26. Rouanne M, Vaessen C, Bitker MO, Chartier-Kastler E, Roupret M. Outcome of a modified York Mason technique in men with iatrogenic urethrorectal fistula after radical prostatectomy. Dis Colon Rectum 2011;54:1008–1013. PMID: 21730791.

27. Pera M, Alonso S, Pares D, Lorente JA, Bielsa O, Pascual M, et al. Treatment of a rectourethral fistula after radical prostatectomy by York Mason posterior trans-sphincter exposure. Cir Esp 2008;84:323–327. PMID: 19087778.

28. Castillo OA, Bodden EM, Vitagliano GJ, Gomez R. Anterior transanal, transsphincteric sagittal approach for fistula repair secondary to laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: a simple and effective technique. Urology 2006;68:198–201. PMID: 16806424.

29. Noldus J, Fernandez S, Huland H. Rectourinary fistula repair using the Latzko technique. J Urol 1999;161:1518–1520. PMID: 10210386.

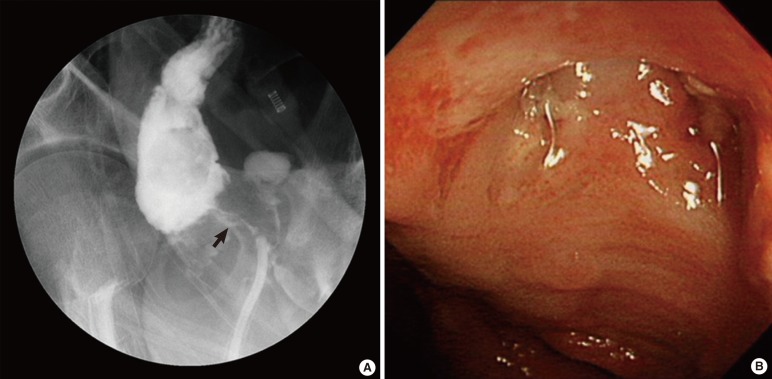

Fig. 1

Diagnostic procedures of rectourethral fistula. (A) Fistulography showing the rectourethral fistula tract. (B) Colonoscopic view of the fistulous opening in the rectum.

Fig. 2

Gracilis muscle flap interposition. A 75-year-old male underwent seed implantation for brachytherapy. About nine months later, a rectourethral fistula (RUF) developed, and a diversion colostomy was performed. However, the RUF persisted for a year after the diversion, so the patient was referred to our hospital to receive a radical retropubic prostatectomy and restoration of a colostomy with a simultaneous gracilis muscle flap interposition. The gracilis muscle harvested from its bed (A) was rotated into the fistula site (B) through a capacious subcutaneous tunnel made between the perineum and the thigh (C).

Fig. 3

Omental flap interposition. A 49-year-old male patient was severely injured in a traffic accident, and a double diversion was performed immediately. Because he had to undergo exploration for other potential intra-abdominal injuries, a transabdominal approach with omental flap interposition and concomitant sigmoidostomy were performed. (A) An omentectomy along the right gastroepiploic arcade was done while the left gastroepiploic pedicle was saved. (B) The omental flap was used to cover the fistula site. (C) The fistula tract was removed, and primary repair was performed.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

- Related articles in ACP

-

Crohn's Anal Fistula and Perianal Abscess: Results of Surgical Treatment.2007 December;23(6)