INTRODUCTION

In patients undergoing screening for prostate cancer, an elevated prostate-specific antigen (PSA) or a rectal exam with concerning findings will typically lead to a prostate biopsy to evaluate for malignancy. The transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)-guided prostate biopsy is the most widely used method to obtain a tissue diagnosis [1,2] and may involve between 6 and 18 core biopsy samples, depending on which protocol is used [3,4,5]. Although the procedure is generally well tolerated, a number of important complications may arise from this procedure that result in 30-day hospital admission rates ranging from 1.0% to 6.9%, with a 2.65-fold increased risk of hospitalization compared to the general population [6]. A retrospective analysis of 1,875 patients undergoing a TRUS-guided prostate biopsy found that the most common reasons for hospitalization were acute prostatitis (3.8%), acute urinary retention (2.1%), and hematuria (1.9%) [7]. Although the overall incidence of rectal bleeding after a TRUS biopsy is reported to range from 0% to 37%, severe rectal bleeding requiring hospitalization is uncommon, 0.2% according to Chiang et al. [7]. A life-threatening rectal hemorrhage requiring transfusions is rare and is limited to case reports. To our knowledge, we report the first case of successful treatment with endoscopic band ligation of a massive hemorrhoidal hemorrhage following a TRUS biopsy.

CASE REPORT

A 77-year-old male with no significant past medical history presented to our medical center's Emergency Department with symptoms of bright red blood per rectum. Two years prior, the patient had undergone a TRUS-guided prostate biopsy at an outside hospital for an elevated PSA of 7 ng/mL (normal <4 ng/mL) and was found to have a Gleason score of 6. The patient elected to pursue surveillance, and in the following year, his PSA was 5 ng/mL. One month prior to presentation at our facility, the PSA was 6 ng/mL. Four days prior to presentation, the patient had undergone a repeat TRUS-guided prostate biopsy in the other hospital's urological procedure room. No immediate complications were encountered, so the patient was sent home. Several hours later, he developed lightheadedness and bright red blood per rectum. Upon returning to the outside hospital, he developed syncope and was taken to their Emergency Department, where he had ongoing bright red blood per rectum. The hemoglobin was found to have decreased from a preprocedural level of 12.9 g/dL (normal, 13.5??7.5 g/dL) to 9.7 g/dL. Computed tomography (CT) angiography of the abdomen and pelvis showed active bleeding in the rectum. The patient was observed, and his bleeding appeared to self-resolve. He was not given blood products and was discharged on the next day, 3 days prior to his presentation at our medical center.

On the evening of the fourth day postprocedure, the patient again developed lightheadedness and bright red blood per rectum. He was brought to our Emergency Department for further evaluation. He had not taken any medications. His temperature was 36.3℃, his heart rate 110 per minute, his blood pressure 109/62 mmHg, and his oxygen saturation was 96% on room air. On physical examination, he appeared diaphoretic and pale; no abdominal tenderness was found. Laboratory studies revealed a hemoglobin level of 7.7 g/dL. The platelets, prothrombin time (PT), and partial thromboplastin time were within their normal ranges. CT angiography of the abdomen and pelvis showed active bleeding in the anterior rectum. Over the next 12 hours, the patient had eight episodes of large-volume bright red blood per rectum and clots. He received seven units of blood and 2 units of fresh frozen plasma. Although the patient was alert and oriented at the time of presentation, he subsequently developed syncope with poor arousability and was intubated in our intensive care unit for airway protection. A 500-mL tap water enema was administered, and he underwent flexible sigmoidoscopy.

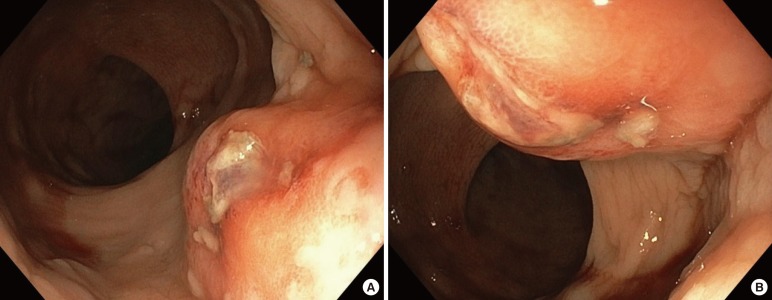

On sigmoidoscopy, bright red blood and clots were noted from the rectum to 15 cm of intubation, where normal mucosa was visualized. On the anterior aspect of the rectum, at 1 to 2 cm from the dentate line, an approximately 3-mm ulcerated lesion was noted overlying a raised lesion that was pulsatile (Fig. 1). Six mililiters of 0.0001% epinephrine solution was injected circumferentially around this lesion, with immediate brisk bleeding noted at the injection sites. Although clipping and/or cautery were initially considered for hemostasis, on retroflexion, the lesion was apparently contiguous with what appeared to be a large internal hemorrhoid (Fig. 2). As such, band ligation (Speedband Superview Super 7, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) was performed using a single band around the site of the ulcerated lesion, with successful hemostasis being achieved (Fig. 3). After the procedure, the patient had no further signs of bleeding and showed stable hemoglobin levels on serial testing. He was successfully extubated within 24 hours and was discharged 5 days later.

DISCUSSION

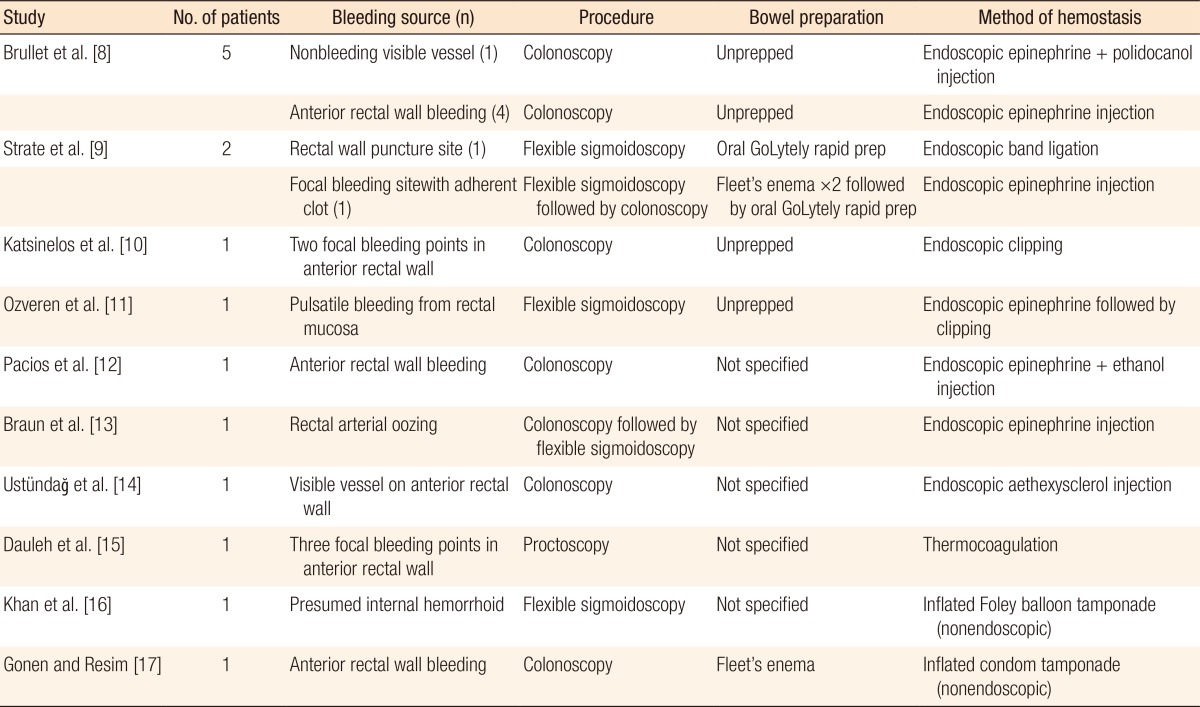

Although rare, life-threatening rectal hemorrhage can occur following a TRUS-guided prostate biopsy. In our review of the literature, we found a total of 15 reported cases of a rectal hemorrhage requiring red cell transfusion (Table 1) [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Two of the cases were ultimately managed using a rectal balloon tamponade. In the remainder, hemostasis was achieved through endoscopic methods, including epinephrine injection alone, sclerosant injection alone, epinephrine plus sclerosant injection, thermocoagulation, endoclipping, and band ligation. The majority of cases noted bleeding from focal puncture sites along the anterior rectal wall. Only 1 previous case posited internal hemorrhoid puncture as the cause of the hemorrhage; that case was managed successfully using a balloon tamponade. To our knowledge, this is the first case of hemorrhoidal bleeding caused by a puncture during a TRUS biopsy procedure being successfully managed by using band ligation.

In patients undergoing an endoscopic evaluation of a rectal hemorrhage after a TRUS biopsy, the practices regarding bowel preparation vary. In our estimation, a complete colonoscopy preparation is probably unnecessary and may delay therapy, as the bleeding is overwhelmingly likely to be immediately proximal to the anal verge, as in our case. Prior to sigmoidoscopy, we elected to perform tap-water enemas primarily to clear blood and clots that might otherwise have been difficult to irrigate and aspirate endoscopically. On flexible sigmoidoscopy, the anterior wall was found to have an apparent hemorrhoid with a focal ulcerated lesion. We presume that a core biopsy had been obtained through this internal hemorrhoid, which resulted in severe, recurrent hemorrhage, despite the lack of anti-platelet or anticoagulant agents or other known coagulopathy.

In evaluating the bleeding risk of a TRUS biopsy, one must consider the anorectal vascular anatomy. Branches of the middle and the inferior rectal arteries supply the distal rectum, and a rich arteriovenous hemorrhoidal plexus lines the anal canal. In patients with hemorrhoids, this plexus may be substantially dilated, increasing the theoretical risk of puncture or shearing during a TRUS biopsy, especially if a higher number of cores are obtained [18]. As such, caution should be taken in performing TRUS-guided prostate biopsies in patients with a known history of hemorrhoids. At minimum, a targeted history and rectal exam should be performed prior to the planned TRUS biopsy. If concern for large hemorrhoids exists, especially in a patient on antiplatelet and/or anticoagulant agents, consideration should be given to a transperineal biopsy approach [19]. We recommended that our patient avoid TRUS biopsy procedures in the future. In summary, although the literature suggests that numerous modalities may achieve hemostasis after massive TRUS biopsy bleeding, our case demonstrates that band ligation can be an extremely effective and well-tolerated treatment.