Hematochezia due to Angiodysplasia of the Appendix

Article information

Abstract

Common causes of lower gastrointestinal bleeding include diverticular disease, vascular disease, inflammatory bowel disease, neoplasms, and hemorrhoids. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding of appendiceal origin is extremely rare. We report a case of lower gastrointestinal bleeding due to angiodysplasia of the appendix. A 72-year-old man presented with hematochezia. Colonoscopy showed active bleeding from the orifice of the appendix. We performed a laparoscopic appendectomy. Microscopically, dilated veins were found at the submucosal layer of the appendix. The patient was discharged uneventfully. Although lower gastrointestinal bleeding of appendiceal origin is very rare, clinicians should consider it during differential diagnosis.

INTRODUCTION

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding of appendiceal origin is very rare and is usually caused by colonic diverticula, angiodysplasia, inflammatory bowel disease, neoplasms, hemorrhoids, and postsurgical complications [1]. Of these causes, angiodysplasia is one of the most common causes of massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding [2]. However, angiodysplasia of the appendix is very rare. Herein, we report a case of lower gastrointestinal bleeding due to angiodysplasia of the appendix.

CASE REPORT

A 72-year-old man visited the Emergency Department with hematochezia. He had mild abdominal pain with a bloating sensation. He denied being nauseous or vomitous and experiencing hematemesis. He had been taking aspirin to treat angina for 10 years. He had a past history of melena due to a duodenal ulcer 2 years earlier. At admission, the patient's vital signs were within normal ranges. Physical examination did not reveal abdominal tenderness. Laboratory investigations revealed the following: white blood cell count, 8,910/mm3 (44.0% neutrophils); hemoglobin, 12.6 g/dL; hematocrit, 38.0%; platelet count, 125 × 103/mm3; prothrombin time, 13.2 seconds (international normalized ratio, 1.08); creatinine, 1.34 mg/dL; serum Na, 139 meq/L; and serum K, 4.8 meq/L.

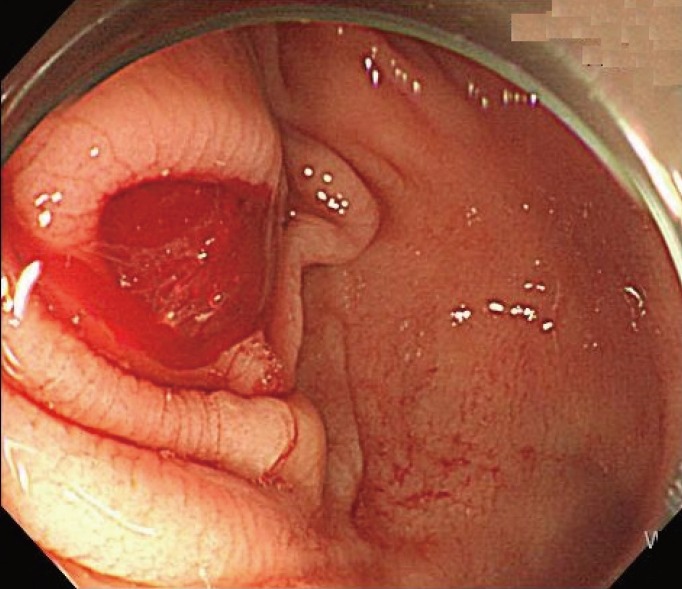

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed gastric and duodenal ulcers, but no evidence of acute bleeding. Colonoscopy showed dark blood fill without definitive evidence of bleeding foci in the entire colon or rectum and revealed that active bleeding originated from the orifice of the appendix (Fig. 1). Otherwise, few diverticula without bleeding were present in the proximal part of the ascending colon and the cecum. No blood clots were found in the proximal part of the ileocecal valve. On the double-phase abdominopelvic computer tomography scan, we noted mild wall thickening in the appendix.

A laparoscopic appendectomy and cecum wedge resection were performed. The appendix appeared grossly to be mildly edematous and hyperemic on the serosal surface and had a maximum diameter of 8 mm and a length of 48 mm. A small ulcer-like lesion was found on the mucosa of the middle part of the appendix (Fig. 2). Microscopically, the submucosa of the appendix was widened with aggregates of dilated vessels, most of which were veins. The submucosal veins pierced the circular and the longitudinal muscle layers of the appendix (Fig. 3A, B). The patient had no hematochezia or melena after surgery. The patient was discharged uneventfully eight days after surgery.

The microscopic findings showed small ulcers or erosions in the mucosa of the appendix (blue arrows). (A) Submucosal veins pierced the circular and the longitudinal muscle layers of the appendix (†). The submucosa was widened with aggregates of dilated vessels (black arrows), most of which were veins (H&E, ×20). (B) Most of the dilated vessels were veins (H&E, ×100).

DISCUSSION

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding is defined as bleeding that starts below the ligament of Treitz and represents approximately 20% of all forms of gastrointestinal tract bleeding [3]. Bleeding from the appendix is very rare. Appendiceal bleeding is more common in males than in females (male : female=2 : 1), and the mean age of previously-surveyed patients was 40.6 years (range, 9–72 years). The histopathologic findings of appendiceal bleeding are ulcer, erosion, diverticulitis, diverticulum, intussusceptions, mucoceles, acute appendicitis, Crohn's disease, gastrointestinal stromal tumor, angiodysplasia and endometriosis [4]. Vascular diseases of the colon are common causes of massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding [2]. Appendiceal bleeding due to vascular disease, such as angiodysplasia, arteriovenous malformation, and Dieulafor lesion, is extremely rare [567]. This case is the fourth case of appendiceal bleeding due to vascular disease ever described.

Angiodysplasia is a common cause of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. The terms "angiodysplasia" or "vascular ectasia" indicate mucosal vascular malformation confined to the gastrointestinal tract [5]. The cause of such bleeding remains obscure. Obscure, intermittent, low-grade obstruction to submucosal veins may lead to dilation and tortuosity. In our case, the submucosa was widened with aggregates of dilated vessels, most of which were veins.

Appendiceal bleeding is very rare and, therefore, hard to detect as a cause of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Various diagnostic tools, such as barium-enema, colonoscopy, mesenteric artery angiography, and abdominal CT scan, are used for the diagnosis of appendiceal bleeding. In our case, colonoscopy directly revealed that the bleeding originated from the appendiceal orifice. Therefore, colonoscopy was critical to the diagnosis not only of lower gastrointestinal bleeding but also appendiceal bleeding. Colonic angiodysplasia can be managed by using colonoscopic procedures. However, lesions of appendiceal angiodysplasia cannot be seen directly and cannot be managed with colonoscopy. Angiography complements colonoscopy because it can detect additional lesions in other parts of the gastrointestinal tract, which may occur in 17% of patients with colonic angiodysplasia [8]. Although diagnosis by mesenteric artery angiography requires bleeding more than 0.5 mL/min, vessel embolization can be performed as soon as diagnosis is complete.

Many options are available for the treatment of patients with appendiceal bleeding. When the condition is diagnosed by using mesenteric artery angiography, vessel embolization is an option. Various types of surgical treatments, such as an appendectomy, partial cecectomy, ileocecectomy, and right hemicolectomy, have been attempted [4], so to select the best surgical options to treat patients with appendiceal bleeding, clinicians must consider the disease's characteristics and locations, as well as concomitant diseases. In summary, although appendiceal bleeding is very rare, clinicians must always consider it as a possible cause of lower gastrointestinal bleeding.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.