Multiple Presacral Teratomas in an 18-year-old Girl: A Case Report

Article information

Abstract

Although the sacrococcygeal area is the most common site for a teratoma in infants, it is a rare site for a teratoma in older patients. Most of the teratomas found in this area in adults are single mass, but in a few cases, multiple masses have been reported. The author reports on the case of an 18-year-old female patient with 3 presacral teratomas. The tumors were surgically removed via a transabdominal approach and were pathologically diagnosed as mature cystic teratomas. This case report indicates that an adult presacral teratoma can appear as multiple tumors, although it is very unusual.

INTRODUCTION

Teratomas are composed of various cell types, which represent more than one germ layer. Sacrococcygeal teratoma is the most common solid neoplasm in neonates, with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 35,000-40,000 births. They can be diagnosed prenatally by fetal ultrasound; 50-70% of cases are found during the first few days of life, with less than 10% being diagnosed beyond the age of 2 years [1]. Case reports on adult teratoma in this anatomic site are very rare. Complete surgical resection is necessary to alleviate symptoms and to rule out malignancy because malignant transformation has sometimes been reported [2]. Almost all reported cases of adult teratomas have been found as a single tumor, so multiple masses are extremely unusual. We report a case of adult teratoma found as multiple tumors in the presacral area.

CASE REPORT

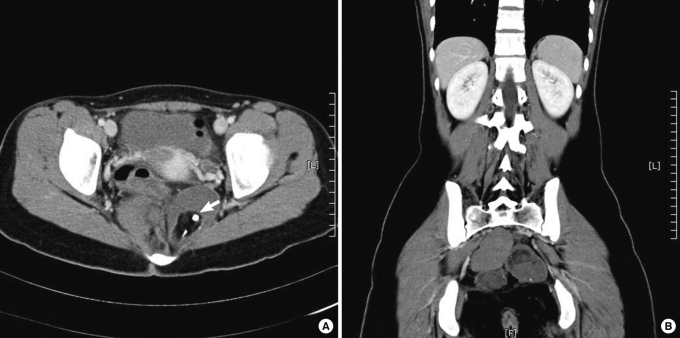

An 18-year-old female was transferred to our outpatient department from a local hospital. The patient had had an appendectomy 3 months earlier due to acute appendicitis. A CT scan was performed for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis, and 3 presacral masses were revealed. A regularly marginated mass measuring 5.5 cm was identified in the left retrorectal space and extended into the ischiorectal fossa (Fig. 1A). It contained heterogenous tissue elements, including inhomogeneous fatty tissue, fluid and calcifications. A high-density mass measuring 6 cm was observed in the right retrorectal area. On coronal view, another nodule measuring 3 cm was found just beneath the mass mentioned above (Fig. 1B). The 3 masses were contiguously located; however, all of them were individually circumscribed and were, thus, regarded as independent masses rather than lobulating daughters budding from one mass. No evidence of bone destruction or invasion of the adjacent structures was found. On digital rectal examination, a non-tender mass was palpated at the posterior rectum. Routine laboratory tests were within normal ranges. Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and serum markers, alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and carbohydrate antigens (CA 19-9, CA 125), were not elevated. No kinds of accompanying congenital abnormalities were found on the clinical and imaging studies.

(A) CT scan of the pelvis demonstrating two masses in the presacral space. Note calcifications (arrow) within fat tissue in the left cyst. (B) Coronal view showing three discrete masses.

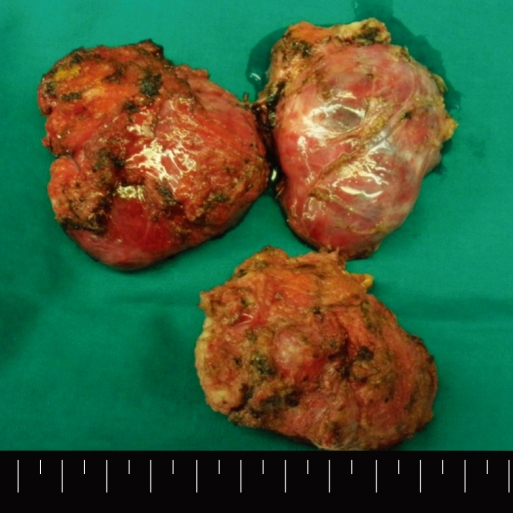

Considering the multiplicity of the masses, a transabdominal approach was selected. All three masses were removed completely (Fig. 2). The right upper mass was filled with hair material and a cloudy fluid. The fluid was partially aspirated to facilitate dissection. The right lower mass showed dense adherence to the sacrum and was filled with sebaceous material and hair. The mass was resected without removal of the coccyx bone although it was adhered to the sacrum. The left lateral mass contained soft solid tissue and fluid-filled cysts. Sebaceous material was also aspirated from the cyst in order to obtain a better operative view. The solid portion contained mainly fatty tissue and calcifications (Fig. 3). Histopathological evaluation revealed a vast spectrum of tissue types characteristic of a teratoma. All three germ layers appeared in all 3 tumors: fragments of squamous epithelium, hair, sebaceous glands, and neural glia (ectodermal derivation); adipose tissue and bone (mesodermal derivation); and respiratory epithelium (endodermal derivation). No malignant or immature cells were found, and a diagnosis of mature cystic teratoma was made. The patient recovered without showing any postoperative complication.

The specimen shows three well-encapsulated masses. Since the cystic contents were partially aspirated during dissection, the size of the mass seen in the specimen is smaller compared to the original one.

DISCUSSION

Teratomas contain tissues that are foreign to their anatomic site and have not resulted from metaplasia. They are derived from embryonic pluripotent cells and may have various degrees of maturation, according to which they are classified as mature, immature, and malignant [3]. They may be inherently malignant or have the potential for malignant degeneration. Among the pediatric population, there is a tendency toward malignant transformation of sacrococcygeal teratomas with increasing age. The incidence of malignancy is 7-10% when diagnosis is made prior to the age of 2 months, compared with 50-67% when the diagnosis is established after that age [4]. However, benign tumors predominate in case reports involving adult populations [5, 6]. The possibility of malignancy should be kept in mind when planning the treatment for adult sacrococcygeal or presacral teratomas because cases of malignant transformation have sometimes been reported [2, 5, 7].

With regard to radiologic evaluation, the presence of irregular calcifications has been reported in 75% of benign tumors [8]. Calcifications are also found in 25% of malignant teratomas, so they cannot be considered to be an indicator of benignity [9]. Malignancy is suspected in large tumors with necrosis, poor definition of adjacent soft tissue planes, and sacral infiltration and is certain when locoregional lymph node and distant metastases are noted [8, 9]. Based on this information, the tumor in the present case was considered to have a benign nature in preoperative evaluation, although imaging features alone do not provide definite differentiation between benign and malignant teratomas. In this case, benignity was confirmed using an intraoperative frozen biopsy.

Most teratomas contain both solid and cystic areas, although completely solid teratomas do occur. Teratomas are usually well-encapsulated single masses, and independently encapsulated cysts can rarely be found within one large tumor [10]. However, the appearance of an adult sacrococcygeal or presacral teratoma as multiple masses is extremely rare, and according to a thorough literature review, only one report has shown a case of presacral teratoma exhibiting three cystic masses [11]. Various theories for the origin of teratomas include parthenogenetic development of germ cells within the gonads or in extragonadal sites; nonparthenogenetic origin from "wandering" germ cells left behind during migration of embryonic germ cells from the yolk sac to the gonad; and an origin from other totipotent embryonic cells [3]. Pluripotent cells are normally present in the gonads and may also be found in abnormal sequestered midline embryonic rests. Accordingly, teratomas are found in the mediastinum, the retroperitoneal space, the sacrococcygeal zone and intracranial locations, as well as the gonads. If the pathogenesis of sacrococcygeal or presacral teratomas that are aberrantly sequestered pluripotent cells is considered, the presence of multiple tumors might be possible, as in the reported case, which is very unusual.

Symptoms of presacral teratomas are often subtle and nonspecific; however, completely asymptomatic patients, like the present case, are rare. Most frequently reported symptoms include lower back and pelvic pain, constipation, urinary retention and lower extremity paresthesias or weakness [7, 11]. Symptoms mainly result from the mass effect and rarely from infiltration in the case of malignancy. In fact, these symptoms can be elicited by any type of presacral mass. Differential diagnoses of presacral masses vary with their natures. In adults, presacral simple cystic lesions may correspond to anterior meningoceles or rectal duplication cysts. In the appropriate clinical context, they may also represent abnormal collections, such as seromas or urinomas. In the presence of a multiloculated cystic lesion, a tail gut cyst must be considered. Denser and more complex lesions may represent chronic retrorectal abscesses, pilonidal or dermoid cysts, soft tissue, bone tumors and metastatic tumors. Whatever the nature of the lesion is, a presacral or sacrococcygeal teratoma should be included in the differential diagnosis [10].

CT and MRI are the most significant methods to characterize the mass and to evaluate the intrapelvic extension and relationship to other structures. Both studies are complementary; however, CT is the most sensitive study for demonstrating calcification and ossification in sacrococcygeal teratomas, as well as for determining the integrity of the adjacent cortical bone. MRI allows a better topographic evaluation of the tumor owing to its direct multiplanar characteristics and provides higher resolution in soft tissues. In this case, MRI was not performed because the boundary of the mass was clear on the CT scan. However, for a thorough preoperative study in complicated cases, MRI could be necessary.

Surgical excision is the treatment of choice for presacral teratomas, provided that the tumor can be completely removed. A posterior approach through a sacral incision, a transabdominal approach and a combined approach have been reported, depending on the tumor's size and location. The transabdominal approach is preferred for high lesions without evidence of sacral involvement. This approach has the advantage of providing excellent exposure of important pelvic structures. Recently, laparoscopic excision has also been attempted by some particular surgeons [12, 13].

In conclusion, a presacral teratoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a pelvic mass in adults. An adult teratoma at this site can appear as a multiple tumor, although it is extremely unusual.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.