Clinical Characteristics and Surgical Safety in Patients with Acute Appendicitis Aged over 80

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to evaluate the clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes, including surgical safety, in patients over 80 years of age who underwent an appendectomy.

Methods

This study involved 160 elderly patients who underwent an appendectomy for acute appendicitis: 28 patients over 80 years old and 132 patients between 65 and 79 years old.

Results

The rate of positive rebound tenderness was significantly higher in the over 80 group (P = 0.002). Comparisons of comorbidity, diagnostic tool and delay in surgical treatment between the two groups were not statistically different. American Society of Anesthesiologists score was significantly higher in the over 80 group than in the 65 to 79 group (2.4 ± 0.5 vs. 1.6 ± 0.5; P < 0.00005). Comparisons of operative times and use of drainage between the two groups were not statistically different. In the pathologic findings, periappendiceal abscess was more frequent in the over 80 group (P = 0.011). No significant differences existed between the two groups when comparing the results of gas out and the time to liquid diet, but the postoperative hospital stay was significantly longer in the over 80 group (P = 0.001). Among the postoperative complications, pulmonary complication was significantly higher in the over 80 group (P = 0.005). However, operative mortality was zero in each group.

Conclusion

In case of suspicious appendicitis in elderly patients, efforts should be made to use aggressive diagnostic intervention, do appropriate surgery and prevent pulmonary complications especially in patients over 80 years of age.

INTRODUCTION

Appendicitis is one of the most common diseases causing acute abdominal pain and requiring surgery. By virtue of socioeconomic developments and medical achievements, the proportion of elderly people in the total population is steadily increasing, and accordingly, the prevalence of senile appendicitis is expected to increase at an accelerating rate.

In general, elderly patients have more underlying diseases than younger patients do, and the sluggish physiological functions of their internal organs result in slow recovery and increased risks from anesthesia and surgery [1]. Intense attention is required for senile appendicitis cases, and features such as non-specificity of symptoms, difficulty of early diagnosis, physiological changes, high number of underlying diseases, high perforation rate, high risk of perforation injury and high complication rate must be considered [2-5]. Moreover, diagnosis is often missed by doctors at the first examination due to low prevalence rate or delayed due to lack or absence of support from guardians, economic reasons, fear of visiting hospitals, and inappropriate self-treatments [3, 6]. Fortunately, surgical treatments for elderly patients and the postoperative morbidity and death rates have improved in accordance with developments in perioperative management, anesthesia and surgical methods. In an attempt to improve clinical understanding of super-aged appendicitis patients and to identify effective treatments and changes in clinicopathologic factors in the aging process, in the present study, we investigated the results of treatments and the stability of an appendectomy.

METHODS

Out of the 1,766 patients who were diagnosed with acute appendicitis and underwent an appendectomy at the Department of Surgery, Sahmyook Medical Center, between January 2004 and December 2010, a total of 160 patients (9.1%) who were 65 years of age or older and who had been histologically confirmed with appendicitis were selected for this study to compare and analyze the clinical features, the methods of treatments and the treatment results of appendicitis. The selected patients were divided either into a super-elderly group (aged 80 or over) or an elderly group (aged below 80).

Through individual medical records, various clinical features such as age, gender, time elapsed from onset of symptoms to hospital visit, time elapsed from hospital visit to surgery, methods of diagnosis, blood tests findings, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, time spent for surgery, types of incision, presence of abscess drainage, pathohistological findings, periods of postoperative hospital stay, periods of postoperative fasting and presence of complications were retrospectively analyzed. Abdominal sonography or computed tomography (CT) was conducted for all patients prior to surgery. Perforated appendicitis was defined when histological findings of gangrenous or perforative changes were observed or in case of appendicitis with a periappendiceal abscess. In terms of the method of surgery, an abdominal appendectomy was used in most cases of the present study, and a laparoscopic appendectomy was performed in 16 cases.

Of the total 160 cases, 153 cases (95.6%) underwent surgery within 24 hours of admission. In 67 cases (42%), surgery was performed by a 3rd year or more experienced surgical resident under the supervision of specialist surgeons, and in the remaining 93 surgery cases (58%), surgery was performed by 4 specialist surgeons. The abdominal appendectomy was performed using typical methods with a transverse incision, a paramedian incision or a low midline incision. The laparoscopic appendectomy was performed using the three-port method.

In the statistical processing, the analysis tool Pack (Microsoft Excel 97, 4.00.950, Korean Microsoft Co., Seoul, Korea) was used for the Student's t-test and the chi-square test. When the P-value was less than 0.05, the result was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Incidence by gender and age

Of the 1,766 patients who underwent an appendectomy and were pathohistologically diagnosed with appendicitis, 160 patients (9.1%) 65 years of age or older were selected. Of the 160 patients, 132 (82.5%) belonged to the elderly group (age below 80), and 28 (17.5%) belonged to the super-elderly group (age 80 or above). The eldest patient was a 95-year-old female. The 160 patients were composed of 61 males and 99 females, for a male-to-female ratio of 1:1.62; the ratio for the elderly group was 1:1.44 while that for the super-elderly group was 1:3 (Table 1).

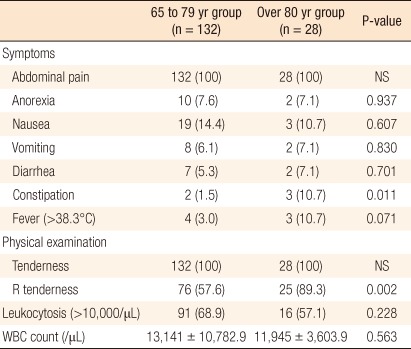

Clinical manifestations and blood test findings

Abdominal pain was found in all cases while low appetite, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and fever developed in both groups without significant difference. By comparison, constipation developed in 1.5% of the elderly group aged and in 10.7% of the super-elderly, with the difference showing statistical significance (P < 0.05). On physical examinations, all cases of the both groups showed findings of tenderness. Rebound tenderness was observed in 89.3% of the elderly group, which was significantly higher than the 59.6% for the super-elderly group (P < 0.005). The ratios of patients having leukocyte counts of 10,000/µL or over were 68.9% and 57.1% in the elderly and the super-elderly groups, respectively, with means of 13,141 ± 10,782.9 and 11,945 ± 3,603.9, but these results showed no statistically significant differences (Table 2).

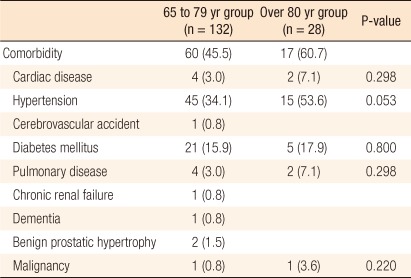

Underlying diseases

Of the elderly and the super-elderly groups, and 45.4% and 60.7% had underlying diseases. The prevalence rates of heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, lung diseases and cancer were 7.1%, 53.6%, 17.9%, 7.1% and 3.6%, respectively, in the super-elderly group, but the differences were not statistically significant (Table 3).

Methods of diagnosis and time elapsed from onset of symptoms to surgery

The numbers of patients who were diagnosed through preoperative history taking and physical examinations, abdominal sonography, and abdominal CT were 24 (15.0%), 59 (36.9%), and 77 (48.1%), respectively. The time elapsed from the onset of symptoms to hospital visit and the time elapsed from hospital visit to surgery were not significantly different between the two groups, and the times elapsed from the onset of symptoms to surgery were 55.27 ± 45.78 minutes and 54.76 ± 51.47 minutes in the elderly and the super-elderly groups, respectively (Table 4).

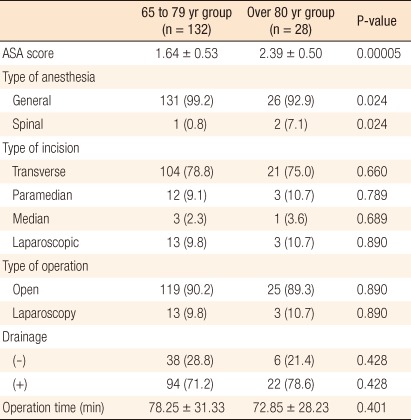

Anesthesia and surgery

ASA scores were 1.64 ± 0.53 in the elderly group and 2.39 ± 0.50 in the super-elderly group, with this difference showing statistical significance (P < 0.00005). In the elderly and the super-elderly groups, 99.2% and 92.9%, respectively, underwent surgery under general anesthesia while the remaining patients underwent surgery under spinal anesthesia. Incisions were made by the decisions of surgeons, and no statistically significant difference existed between the groups in terms of the number of incisions. An abdominal appendectomy was performed in 144 cases while a laparoscopic appendectomy was performed in 16 cases, but the difference between the groups was not significant. Abscess drainage was performed in 94 cases (71.2%) and 22 cases (78.6%) in the elderly and super-elderly groups, respectively, without a significant difference between the groups. The mean operative times of the respective groups were 78.25 ± 31.33 minutes and 72.85 ± 28.23 minutes, with the difference showing no statistical significance (Table 5).

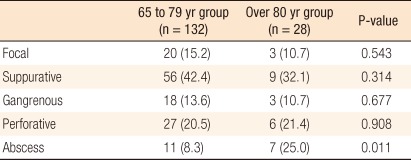

Results of histopathologic examinations

Based on the histopathologic findings, acute appendicitis was classified into 5 types: localized inflammatory, purulent, gangrenous, perforative and apostematous acute appendicitis. When the two groups were compared, no significant differences were found in localized inflammatory, purulent, gangrenous and perforative acute appendicitis, but apostematous acute appendicitis in the super-elderly group was 25.0%, which was significantly higher than the value of 8.3% for the elderly group (P = 0.011) (Table 6).

Postoperative hospital stay, periods of fasting and complications

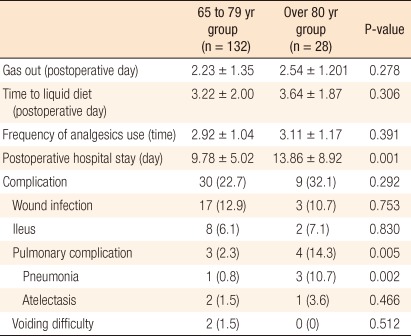

Postoperative gas passing occurred within 2.23 ± 1.35 days and 2.54 ± 1.201 days in the elderly and the super-elderly groups, respectively, and liquid diet intake began after 3.22 ± 2.00 days and 3.64 ± 1.87 days, respectively, showing a slight delay in the superelderly group, but with no statistical significance.

The number of postoperative uses of analgesics in the elderly group was 2.92 ± 1.04 compared with 3.11 ± 1.17 in the super-elderly group, but the difference was not statistically significant. In contrast, the postoperative hospital stay in the elderly group 80 was 9.78 ± 5.02 days compared with 13.86 ± 8.92 days in the super-elderly group, showing a statistically significant difference (P = 0.001).

Postoperative complications developed in 22.7% and 32.1% of the elderly and super-elderly groups, respectively. In terms of pulmonary complications, the super-elderly group showed 14.3% while the elderly group showed 2.3%, a significant difference (P = 0.005). In particular, pneumonia developed in 10.7% and 0.8% of the patients in the super-elderly and the elderly groups, respectively, with the difference showing statistical significance (P = 0.002). In both groups, no cases of death associated with surgery were reported (Table 7).

DISCUSSION

Acute appendicitis is one of the most common diseases requiring emergency surgery. Elderly acute appendicitis patients compose 8.3 to 16.4% of the total acute appendicitis patients in Korea [7-10]. Because of the sharp increase in the elderly population, the prevalence of senile appendicitis has also increased [8], and this trend will continue. Elderly patients usually show anatomically atrophic appendices with reduced lymphatic tissues and diameter stenosis caused by fibrosis. In addition, angiosclerosis often leads to ischemia, and risk of developing early perforation in the appendix due to mesentery dysfunction is high [5]. Further, reduced immune function causes unsatisfactory development of fever and an increase in the number of leukocytes [11, 12]. Abdominal muscular atrophy results in reduced rebound tenderness. Aging may also cause changes in neural responses due to increased pain threshold, abnormal sensation and transfer of pain. In summary, clinical manifestations of elderly patients are non-typical and ambiguous.

As people 65 years of age and older are generally recognized as elderly, patients 65 years of age or older were defined as elderly patients in the present study, and senile appendicitis patients were divided into an elderly group (65 to 79 years of age) and a super-elderly (80 years of age or older). The number of patients who were diagnosed with postoperative appendicitis between January 2004 and December 2010 was 1,766, and the number of senile appendicitis patients 65 years of age or older was 160, comprising 9.1% of the total, which is similar to the ratios, ranging from 8.3 to 16.4%, reported in previous studies in Korea [7-10]. The male-to-female ratio of all senile appendicitis patients was 1:1.06 in favor of females, and the ratio in the super-elderly group was 1:1.62, showing a sharp increase in female proportion. This result is also similar to those of previous reports, which showed increases in the female proportion from 1:1.1 to 1:1.67 [7, 8]. In addition, the ratio in the elderly group was 1:1.44 and sharply increased to 1:3 in the super-elderly group due to female patients living longer than male patients.

Regarding major symptoms, both groups complained of abdominal pain similar to or at a higher level than in previous studies [8-10, 13]. In terms of low appetite, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and fever, no difference was observed in both groups, but constipation was significantly more common in the super-elderly group.

Tenderness was observed through physical examinations in all cases of both groups, and rebound tenderness was significantly higher in the super-elderly group. Consequently, when non-specific gastric symptoms are observed in super-elderly patients, appendicitis should be suspected, and palpation on the right abdomen is necessary to make an early diagnosis.

Leukocytosis is defined as a white blood cell count of 10,000/µL or over, and the values for the elderly and the super-elderly groups were 68.9% and 57.1%, respectively, showing no statistically significant difference between the groups, and these results are similar to those of previous studies [7-10, 13]. The reasons for the slightly lower level (57.1%) shown in the super-elderly group are thought to be the reduced immune responses in elderly patients, weak systemic responses or inflammatory responses, and poor blood circulation [14]. Blood test results are not considered to be good enough for making a diagnosis, but the results should be used in association with clinical manifestations.

In the elderly group, 45.5% of the patients had underlying diseases while 60.7% of the super-elderly group had underlying diseases without statistical difference. Hypertension was most common in both groups, followed by diabetes, heart diseases and pulmonary diseases.

Since symptoms of elderly patients are ambiguous, and differential diagnosis is usually required, diagnostic images are frequently used. In the present study, 24 cases (15.0%) were diagnosed using preoperative history-taking and physical examinations only, 59 cases (36.9%) were done using abdominal sonography, and 77 cases (48.1%) were done using abdomen-pelvic CT. There was no statistical difference between the groups. Use of diagnostic images is increasing because of demands from the medical insurance system and patients/guardians. In addition, diagnostic images are in high demand for cases difficult to make diagnoses based on symptoms or physical examinations only and for cases in which differentiating one disease from other abdominal diseases is necessary.

According to Owens and Hamit [11], when the time that elapsed from onset of symptoms to surgery was prolonged, the perforation rate of the appendix increased. Lau et al. [12] reported that when the time spent before hospital visit exceeded 24 hours, the perforation rate of the appendix increased significantly. However, the total elapsed times (times between the onset of symptoms and surgery) in the present study were 55.27 ± 45.78 minutes and 54.76 ± 51.47 minutes in the elderly and the super-elderly groups, respectively, showing no statistically significant difference. Instead, the onset ratio of apostematous appendicitis in the super-elderly group was significantly higher than that in the elderly group, indicating that age contributes more than the total elapsed time does to the increase in the perforation rate.

In terms of anesthesia, the ASA score in the super-elderly group was significantly higher than that in the elderly group. In terms of the methods of anesthesia, spinal anesthesia was more frequently used, with statistical significance, in the super-elderly group than in the elderly group because the risks involved in anesthesia were seriously taken into consideration for the super-elderly patients. As a result, no deaths were reported in the present study, and surgery was performed safely.

In the present study, acute appendicitis was pathohistologically classified as 5 types: localized inflammatory, purulent, gangrenous, perforative and apostematous acute appendicitis. Regarding the numbers of localized inflammatory, purulent, gangrenous and perforative acute appendicitis, no significant differences were observed between the two groups, but in case of apostematous acute appendicitis, 11 cases (25.0%) were found in the super-elderly group compared with 7 cases (8.35%) found in the elderly group, a significant difference (P = 0.011). Previous studies reported high perforation rates in senile appendicitis cases [14, 15], and the result of the present study not different. The reasons may include reduced periappendiceal lymphatic tissues of elderly patients resulting in a weakened defense mechanism, malnutrition, anemia, vitamin deficiency, reduced elasticity of the appendix, sluggish large intestine functions, and reduced systemic resistance against inflammation [16].

In terms of postoperative gas pass, time of liquid diet intake, and number of uses of analgesics, no significant differences were found between the two groups. With regard to postoperative period of hospitalization, the super-elderly group 13.86 ± 8.92 days in the hospital while the elderly group spent 9.78 ± 5.02 days, a statistically significant difference (P = 0.001). Compared with the results of previous studies [17, 18], the super-elderly group in the present study showed a longer hospital stay. The reason is thought to be related to the desire of elderly patients to remain in the hospital long enough for the surgical wound to heal.

Postoperative complications developed in 39 patients (24.4%). This ratio is similar to the reports of Goldenberg (27%) [19], Hong and Kim (26.9%) [8] and Sim et al. (22%) [9]. The most common complication that developed in the elderly group was wound infection, followed by ileus, pulmonary complications and urological complications. In the super-elderly group, the most common complication was pulmonary complication, followed by wound infection and ileus. Pulmonary complications developed in 14.3% of the super-elderly group, which is significantly higher compared with the 2.3% in the elderly group aged. This implies that for patients 80 years of age or older, more attention should be paid to pulmonary complications.

In conclusion, According to the present study, the elder the patient was, the more apostematous appendicitis was observed even though there was no difference in the time that elapsed from the onset of symptoms to surgery between the elderly (ages 65 to 79) and the super-elderly (age 80 and above 80) groups. In addition, the elder the patient was, the longer the postoperative period of hospitalization was, and the more development of postoperative pulmonary complications was observed. Accordingly, elderly and super-elderly patients who are suspected of having appendicitis based on history or diagnosis and who complain of abdominal pain of unknown cause should be treated with surgery upon completion of active diagnostic examinations; then, attention should be paid to preventing the development of pneumonia.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.