Extended lymphadenectomy in locally advanced rectal cancers: a systematic review

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

The surgical treatment of advanced low rectal cancer remains controversial. Extended lymphadenectomy (EL) is the preferred option in the East, especially in Japan, while neoadjuvant radiotherapy is the treatment of choice in the West. This review was undertaken to review available evidence supporting each of the therapies.

Methods

All studies looking at EL were included in this review. A comprehensive search was conducted as per PRISMA guidelines. Primary outcome was defined as 5-year overall survival, with secondary outcomes including 3-year overall survival, 3- and 5-year disease-free survival, length of operation, and number of complications.

Results

Thirty-one studies met the inclusion criteria. There was no significant publication bias. There was statistically significant difference in 5-year survival for patient who underwent EL (odds ratio, 1.34; 95 confidence interval, 0.09–0.5; P=0.006). There were no differences noted in secondary outcomes except for length of the operations.

Conclusion

There is evidence supporting EL in rectal cancer; however, it is difficult to interpret and not easily transferable to a Western population. Further research is necessary on this important topic.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the commonly diagnosed cancers, being the second leading cancer in women, and the third most common cancer in men [1]. The predicted incidence of CRC might increase to 2.5 million new cases in 2035 [2]. The treatment of advanced cases can be quite complex, especially in the context of rectal cancer. The total mesorectal excision (TME) has been well established in treatment of rectal cancer [3]; however, there is a significant discrepancy in the treatment options offered to patients who have locally extensive disease. This would be defined as clinical stage II or III cancer, located at or below the peritoneal reflection, that has developed metastasis to lateral pelvic lymph nodes, i.e., common iliac, internal iliac, external iliac, and obturator nodes. These nodes can be involved in cases of rectal cancer in 21.9% to 61.1% of cases [4]. The presence of lateral pelvic lymph node involvement confers poorer prognosis to the patient, even when thought to be adequately treated [5]. As such, treating such cases optimally becomes paramount. However, there is currently a difference in consensus regarding the treatment of these cases, largely divided along geographical lines. Western countries, including the United Kingdom and the United States, do not routinely recommend dissection of the lateral pelvic lymph nodes, instead of focusing on neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (CRT) and adequate TME [6, 7]. Eastern countries, particularly Japan, have focused on the lateral pelvic lymph node dissection, extended lymphadenectomy (EL) as a standard treatment for stage II and III low rectal cancer [8]. This review aims to collect all available evidence regarding EL, to assess its feasibility and effectiveness compare its outcomes against standard practice in Western countries.

METHODS

Search strategy

A comprehensive systematic search of the literature was performed in keeping with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. Records on PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, Ovid, Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar were searched for all relevant articles published from January 2008 to January 2019 to give comprehensive current practice review. All articles were published in English language.

The search was performed using the following search terms: “rectal cancer,” “extended lymphadenectomy,” “lateral pelvic lymph node dissection,” “mesorectal excision,” “mesorectum,” and “lateral lymph node.” Abstract and conference proceedings were excluded during preliminary screening due to high risk of incomplete data. Two independent reviewers screened all titles, abstracts, and full-text articles with any disagreement being settled via discussion with the senior author. Publications reporting on the same series of patients were identified and only the most recent data were included.

Types of articles reviewed

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective and retrospective observational studies with controls, and retrospective matched-pair studies were all included.

Studies that did not include a specific section on data for patients, and studies that had fewer than 7 patients (defined as case studies [9]), non-English publications, or studies reported on pelvic exenterations were excluded.

Types of participants

The studies included cases of adults diagnosed with rectal cancer treated by operation with curative intent, which was either standard TME or TME with pelvic sidewall EL.

Types of intervention and comparators

Only studies looking at the operative treatment for locally advanced rectal cancer with or without involved pelvic side lymph nodes, with or without preoperative radiotherapy were included. Comparators were TME vs. EL.

Primary outcome was defined as 5-year overall survival (OS) after TME or EL. Secondary outcomes included 3-year OS, 3- and 5-year disease-free survival (DFS), local and distal recurrence rate, length of operation, number of complications, and volume of blood loss.

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers extracted the data from the papers using a specially designed extraction form. The following data were collected (if reported): 5- and 3-year survival, DFS, OS, number of distant and local recurrence, length of operations, blood loss, and number of postoperative complications.

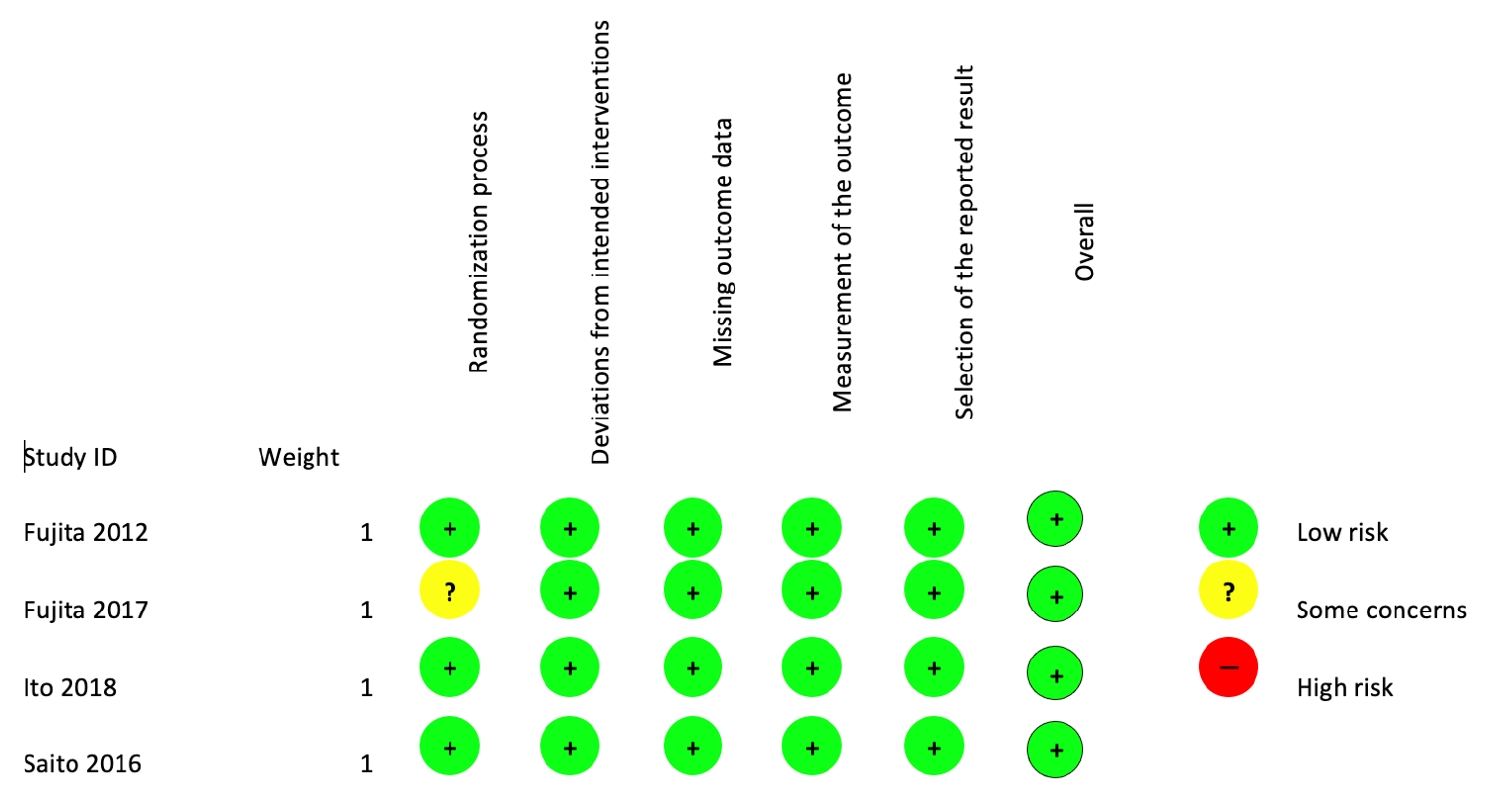

Data analysis

The methodological quality of the study was assessed using the revised Cochrane risk of bias tool to assess in randomized trials [10]. Nonrandomized studies were assessed using the methodological index for nonrandomized studies (MINORS) score [11]. Noncomparative studies scored a maximum of 16 and 24 for comparative papers. Two authors scored all articles included for review independently.

Publication bias was checked by plotting the papers on the Funnel plot and using the Egger test with random effect. The heterogeneity of the study was checked according to Cochrane Collaboration’s Handbook using Q parameter and I2 statistics. I2 less than 40% was considered low heterogeneity. Forrest plot and odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to compare studies and display the results. The P-value for overall effect was calculated using Z-test. All statistical analyses were made with R language with metafor package (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Difference between medians was assessed using quantile estimation according to McGrath et al. [12].

RESULTS

Search results

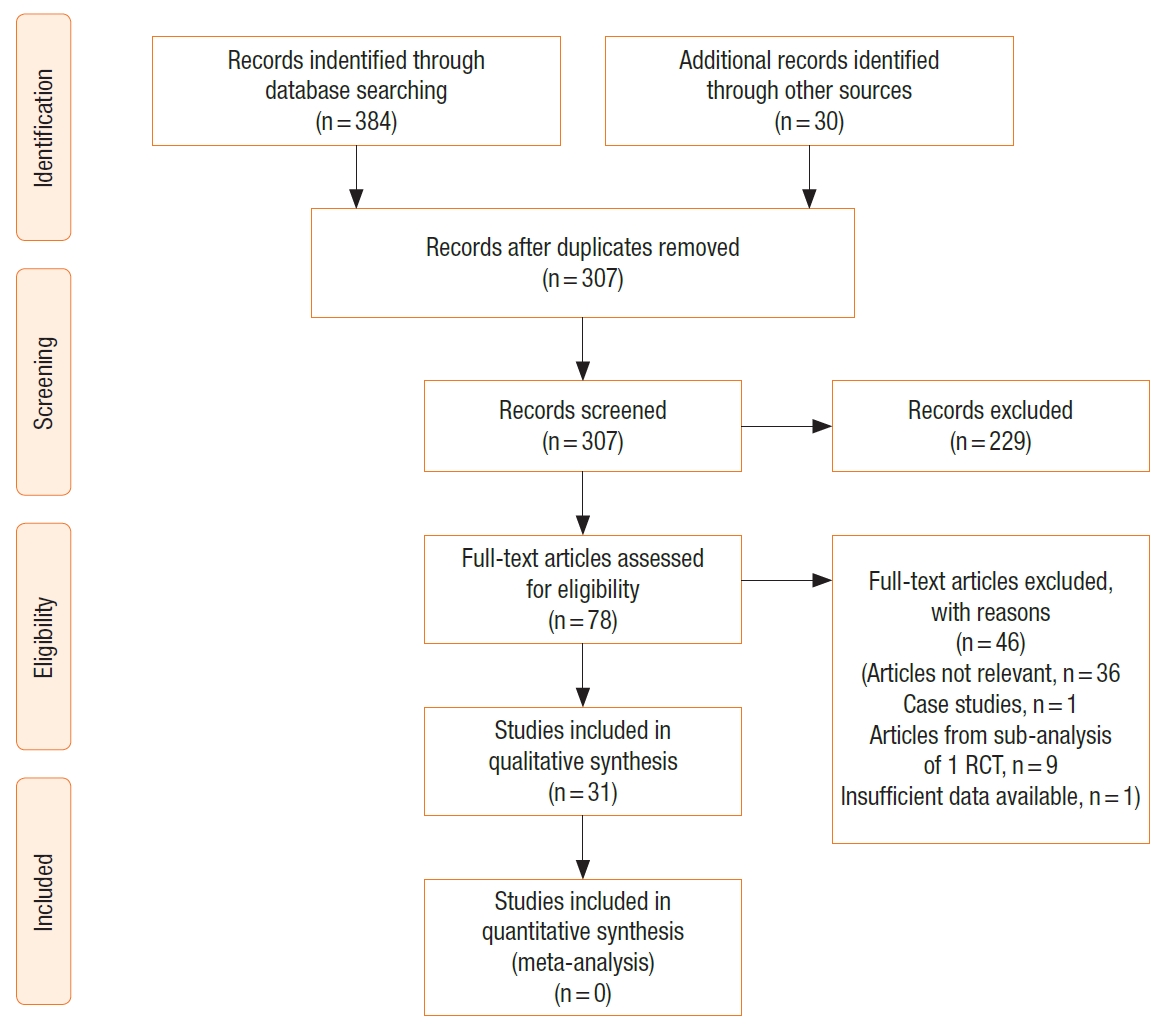

The study selection process is outlined in the PRISMA diagram (Fig. 1). The initial search identified 414 papers. After removing duplications, 307 studies were included in the further text and abstract review. Further 229 studies were excluded after abstract review as they were not relevant, including conference proceedings and abstracts. Seventy-eight papers were reviewed in full text including all references to help identify any other relevant articles not identified through initial search. A further 46 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria (articles not being relevant, 35; case studies, 1, articles with subgroup analysis from 1 RCT, 9; insufficient data available, 1). Finally, 31 articles were included for the systematic review [13-43]. There were no additional studies identified through other sources. The methodological qualities of the studies are represented in Table 1 and Fig. 2. The mean MINORS score was 10.5 with a standard deviation of 3.7 pointing toward low-quality studies (Table 1).

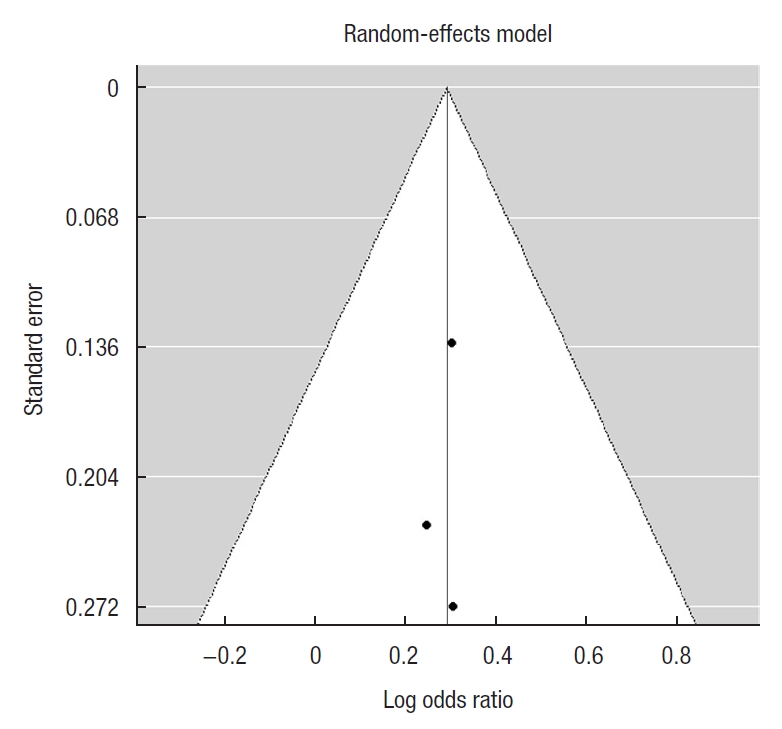

Publication bias and heterogeneity

Calculation of the publication bias was done for primary outcome studies. The Funnel plot was symmetrical and Egger test for mixed-effect meta-regression model was not statistically significant with z=– 0.12, P=0.91 pointing toward the lack of bias (Fig. 3).

Study characteristics

A total of 5,240 patients underwent an EL for the resection of rectal cancer. The major characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 2. Some papers did not publish the mean age for the 2 groups of patients being studied, or published data in a nonstandard way [13, 16, 20, 24, 25, 29, 30, 36, 43], and were not included in the calculation of median age for these patients. The same difficulty arose with the gender breakdown of the patients included in these studies. Furthermore, some papers compared different techniques in performing EL [15, 31] or EL after neoadjuvant chemotherapy [14]. Where possible this data has been included into the overall EL cohort for analysis.

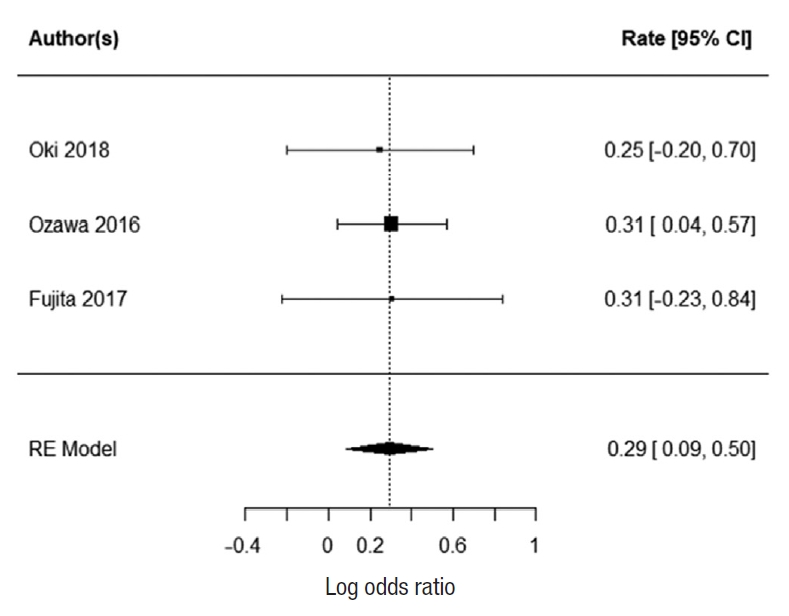

Primary outcome

Three studies report 5-year survival; Oki et al. [23], Ozawa et al. [24], and Fujita et al. [28]. There was no heterogeneity with the data (I2=0%). There was a statistically significant difference in 5-year survival for patients who underwent EL. The summarized random effect is P=0.006 (OR, 1.34; 95 CI, 0.09–0.5) (Fig. 4).

Secondary outcomes

Three-year overall survival

Two studies report 3-year OS; Ogura et al. [21] and Kim et al. [43]. There was no heterogeneity between the study data (I2=0%). There was no statistically significant difference in 3-year survival for patients who underwent EL. The summarized random effect is P=0.55 (OR, 1.27; 95 CI, –0.55–1.03) (Fig. 5).

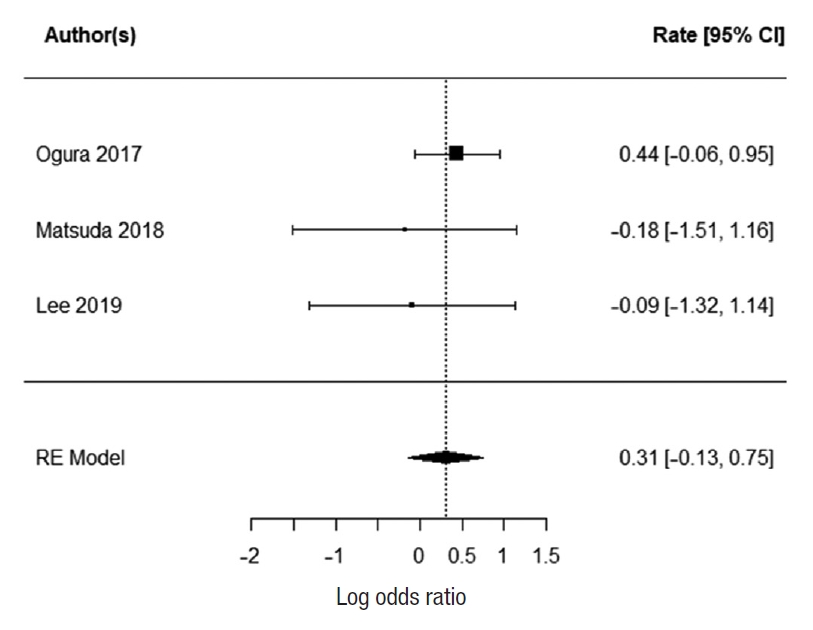

Three-year and 5-year disease-free survival

Two studies reported 3-year DFS; Ogura et al. [21] and Kim et al. [43]. There was no heterogeneity between the study data (I2=0%). There was no statistically significant difference in 3-year DFS for patients who underwent EL. The summarized random effect is P=0.57 (OR, 1.16; 95 CI, –0.37–0.66) (Fig. 6). Five-year DFS was reported in 2 studies; Oki et al. [23] and Fujita et al. [28]. There was weak heterogeneity between the study I2=27.34%. There was no statistically significant difference in 5-year DFS for patients who underwent EL. The summarized random effect is P=0.15 (OR, 1.27; 95 CI, –0.09-0.57) (Fig. 7).

Local recurrence

Six paper reported the number of local and distal recurrence [15, 17, 23, 28, 40, 43]. For local recurrence, there was significant heterogeneity between the studies (I2=79.2%); therefore, it was not possible to summarize it with random effect. The reported mean local recurrence rate was 10.2% (range, 6%–24.3%) for EL and 12% (range, 0%–22.9%) for TME. The 3 papers that reported distal recurrence [15, 17, 23] at 66%, 10%, and 13%, respectively had low heterogeneity between them (I2=0%). The summarized random effect was not statistically significant (P=0.25; OR, 1.25; 95 CI, –0.15–0.59) (Fig. 8).

Other surgical outcomes

Five papers reported the length of operation [17, 18, 21, 26, 33]. There was low heterogeneity between the studies (I2=0%). The EL was significantly longer than TME with summarized random effect (P<0.0001; 95 CI, 94.03–122.10). Three papers reported the numbers of complications [17, 18, 21] with low heterogeneity (I2=0%). The summarized random effect was not statistically significant (P=0.17; OR, 1.36; 95 CI, 0.013–0.75) (Fig. 9).

Five papers report the blood loss after TME and EL [17, 18, 21, 26, 33] (Table 3). There was significant heterogeneity between the papers with I2=87.41% therefore it was not possible to summarize it with random effect. The reported mean blood loss for EL was 560 mL (range, 100–582 mL) and 135 mL (range, 30–337 mL) for TME.

DISCUSSION

There is evidence in support EL in rectal cancer patients, improving their 5-year OS. However, there is some difficulty in interpreting these results, as this benefit is not seen in any of the 3-year OS, 3-year DFS, 5-year DFS, or distal recurrence. Only 3 papers reported their 5-year OS. Their individual rates of 5-year OS are presented in Table 4, reporting rates between 79.9% and 92.6%. It is also important to note that Fujita et al. [28] was a large multicenter RCT (JCOG0212). This high-quality paper concluded that the noninferiority of TME alone was not demonstrated, with regards to the primary outcome of a 5-year DFS. It did however use a 90.9% CI to assess the upper limit of the range of the hazard ratio, rather than the accepted 95%. Indeed there were no significant differences in the 5-year OS and 5-year local recurrence-free survival. There was, however, a significantly lower rate of local recurrence in the EL group when compared to the TME group. This is in keeping with what is currently thought to be the justification for an EL. The other difficulty with assessing the data from JCOG0212 is that EL was performed as a prophylactic measure and none of the patients received radio or CRT to the pelvis which is currently not recommended as a standard practice in stage III cancer in Japan. This is contrary to standard practice in Western countries where radiotherapy to the pelvis is frequently used to downgrade the tumor. Moreover, patients were only included in JCGO212 if they had no extramesorectal lateral lymph node enlargement on preoperative magnetic resonance imaging. This is also contrary to the Western practice where EL is recommended to the cases with enlarged pelvic sidewall nodes, especially persistent after radiotherapy.

Local recurrence is an important factor in considering the merits of EL over a TME. We were not able to summarize the risk of local recurrence in our review; however, there was no difference in the rates of distal recurrence. This brings into question the homogeneity of these patients, and the views of the surgical community with regards to the labeling of the spread of this disease. Western countries consider pelvic lymphadenopathy a sign of systemic disease, whereas the Japanese cohort considers this a local spread of cancer [44]. The effects of local recurrence are also uncertain, with its impact on survival and functional outcomes before and after CRT not well studied.

As expected, EL took longer to perform than TME. This is not in itself a poor prognosticator; however, using the number of all complications as a secondary marker would suggest that it does not affect the patient on average. These procedures were mostly performed by high-volume centers, suggesting a limitation for how short the procedure can be even when performed by experienced surgeons. Additionally, one needs to take into consideration that EL in Western practice is significantly less common; therefore, the operative time and number of postoperative complications may be higher than reported.

It is difficult to have an overall impression regarding the efficacy of EL over TME and radiotherapy. The biology of these tumors is difficult to study, with regards to them being aggressive either locally or distally. Our review suggests there is a partial benefit to performing EL in these patients. However, it is important to note that in performing an EL, many at-risk structures are encountered, including pelvis blood vessels and nerves. These confer a significant effect on the quality of life of such patients. The American National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines suggest an EL is not indicated in the absence of clinically suspected nodes, and some studies have suggested that the effect of neoadjuvant CRT is enough to reduce the number of clinically evident lymph nodes in a rectal resection specimen [45]. There is clearly a need to consider standardization of therapy, as even within the United Kingdom there are varying numbers of therapies used to treat such patients [46]. The JCOG0212 study is a step in the right direction in assessing the efficacy of such treatment, showing promising results. There will be difficulty with regards to the applicability of such a study in the Western population, and this is good point to consider a multicenter RCT or well-designed observational study in the Western population of patients with stage III rectal cancer and positive nodes in the pelvic sidewall.

There is evidence supporting EL in stage III rectal cancer; however, there are difficulties in the applicability of these results straight to clinical practice in the Western population. This is caused by the lack of homogeneity of the populations being studied, especially in relation to the use of preoperative pelvic radiotherapy. Further studies focusing on the Western population would be an important next step in evaluating this treatment modality.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.