Prolapse of intestinal stoma

Article information

Abstract

Stoma prolapse can usually be managed conservatively by stoma care nurses. However, surgical management is considered when complications make traditional care difficult and/or stoma prolapse affects normal bowel function and induces incarceration. If the stoma functions as a fecal diversion, the prolapse is resolved by stoma reversal. Loop stoma prolapse reportedly occurs when increased intraabdominal pressure induces stoma prolapse by pushing the stoma up between the abdominal wall and the intestine, particularly in cases of redundant or mobile colon. Therefore, stoma prolapse repair aims to prevent or eliminate the space between the abdominal wall and the intestine, as well as the redundant or mobile intestine. Accordingly, surgical repair methods for stoma prolapse are classified into 3 types: methods to fix the intestine, methods to shorten the intestine, and methods to eliminate the space between the stoma and the abdominal wall around the stoma orifice. Additionally, the following surgical techniques at the time of stoma creation are reported to be effective in preventing stoma prolapse: an avoidance of excessive fascia incision, fixation of the stoma to the abdominal wall, an appropriate selection of the intestinal site for the stoma orifice to minimize the redundant intestine, and the use of an extraperitoneal route for stoma creation.

INTRODUCTION

Stoma prolapse is classified as a late stoma-related complication [1]. Stoma prolapse is one of the most frequent late complications, and it often induces difficulty in stoma care and affects ostomates’ quality of life. This review presents a concept/definition and information on the incidence of stoma prolapse, causes and risk factors, pathophysiology, treatment selection and indications for surgery, a classification of surgical treatments according to pathophysiology, the present state of surgical treatments, and steps to prevent stoma prolapse.

CONCEPT AND DEFINITION

Stoma prolapse is defined as “an abnormal protrusion of the stoma after creation” according to Terminology of Stoma and Continence Rehabilitation Science, 4th edition [2]. The Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society (WOCN) guideline defines stoma prolapse as an expansion of the intestine from the stoma [3]. One author defines it as “a full-thickness protrusion of the bowel through the stoma site” [4]. Another author explains that stoma prolapse is diagnosed when the stoma increases in size after maturation, requiring a change of appliance or surgical treatment [5]. These definitions have not specified the length of the prolapsed stoma. According to the literature [6], the length of a prolapsed stoma that requires surgical repair is more than 6 to 7 cm. Therefore, Arumugam et al.’s definition [5] as an increase in stoma size after maturation requiring a change of appliance or surgical treatment can be applied to a prolapsed stoma that is more than 6 to 7 cm in length.

The stoma length usually changes to some degree after stoma creation. Stoma prolapse becomes clinically problematic when it involves difficulty of fitting a stoma appliance and stoma care, incarceration, and obstruction of stool outlet. Therefore, these factors might need to be included in the definition of stoma prolapse in the future.

INCIDENCE

The incidence of stoma prolapse ranges widely, from 1.7% to 25% according to the literature [5, 7-14]. This variety in the reported incidence might be dependent on the organ targeted (small intestine or colon), the type of stoma (loop or end stoma), the follow-up period, and the method used to create the stoma, as detailed later. Stoma prolapse is reported to occur in 8.1% to 25.6% of children [15], 2% to 3% of ileostomy patients, 2% to 10% of colostomy patients [16-20], and up to 30% of transverse colostomy patients [21, 22]. Stoma prolapse is reported to occur more often in loop stomas (2%–42%) than in end stomas, and its likelihood of occurring increases with the length of the follow-up period [7, 10, 13]. The odds ratio of stoma prolapse in ileostomy/colostomy is 0.21 (95% confidence interval, 0.3–0.99), and stoma prolapse occurs significantly more often in colostomy than in ileostomy (ileostomy, 6 of 261 < colostomy, 35 of 220) according to a meta-analysis [23]. However, another report showed that the incidence of stoma prolapse was 11.8% in end colostomy [11, 24], whereas the incidence of loop ileostomy prolapse reached 11% during long-term follow-up at the same institution [13]. Stoma prolapse often involves the distal side of a loop stoma [4, 22, 24-28].

CAUSES AND RISK FACTORS

Advanced age, obesity, an increase in abdominal pressure, chronic obstructive lung disease, weakness of the abdominal fascia, and redundant intestine have been listed as physiological causes and/or risk factors [16, 28]. As operation-associated risk factors, an excessive orifice or redundant intestine at the stoma site, excessive space between the abdominal wall and stoma, a stoma site outside the abdominal rectus muscle, stoma construction through intraabdominal route, and the absence of fixation of the mesenterium to the abdominal wall have been documented [28-31]. However, a report stated that stoma prolapse was less frequent in cases using the retroperitoneal route (3 of 40 cases, 7.5%) than in those using the intraperitoneal route (4 of 29 cases, 13.7%), but the difference between these groups was not statistically significant [32]. Concerning the stoma site, frequency of stoma prolapse was 2.4% (1 of 41 cases), 26.5% (13 of 49 cases), and 0% (0 of 5 cases) respectively in cases with the stoma placed through the rectus abdominal muscle, between the rectus abdominal muscle and through the abdominal oblique muscle. The frequency was significantly lower in cases with the stoma placed through the rectus abdominal muscle than in those placed in between the rectus abdominal muscle and abdominal oblique muscle, but the frequency was not necessarily higher in cases where the stoma was placed through the abdominal oblique muscle [32].

Furthermore, another report showed that fixation of the mesentery during stoma construction did not decrease the frequency of stoma prolapse [11, 25]. It has been pointed out that stoma prolapse may be associated with inadequate fixation between the stoma and the abdominal wall, and therefore may be associated with a peristomal hernia [33].

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

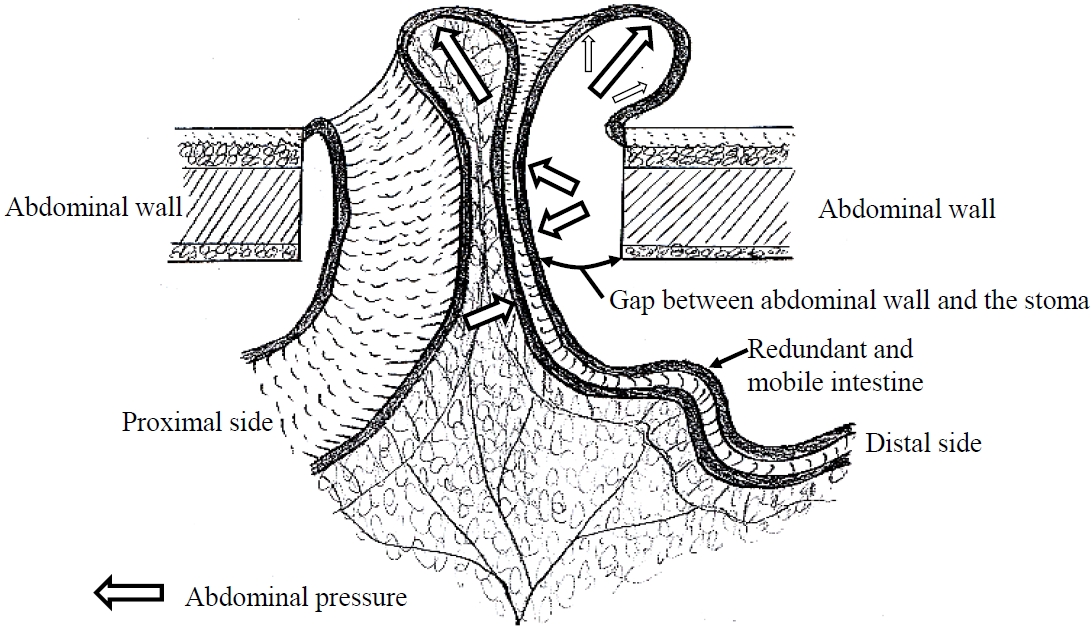

The pathophysiology of stoma prolapse is shown in Fig. 1. Stoma prolapse is induced by the addition of abdominal pressure into the space between the stoma and the abdominal wall by the occurrence of a mobile or redundant intestine. The redundant intestine is then pushed up gradually to prolapse the stoma [29]. Considering the previously described causes and risk factors under the category of redundant intestine, a space between the stoma and the abdominal wall may be caused by the following factors: advanced age, obesity, weakness of the abdominal fascia, an excessive orifice at the stoma site, a stoma site located outside the abdominal rectus muscle, and stoma construction through the intraabdominal route. When a parastomal hernia coexists with stoma prolapse, the space between the stoma and the abdominal wall is further widened. Chronic obstructive lung disease is a common cause of increases in abdominal pressure. Furthermore, a mobile intestine may inverse and gradually prolapse through abdominal pressure. Antiperistaltic movement might be associated with prolapse of the distal limb of a loop stoma, but this has not been proven.

SELECTION OF TREATMENT AND INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY

Stoma prolapse is classified as a fixed type or sliding type involving repeated prolapse and reduction [34], but this classification is not associated with the treatment method. The proposed classification of severity of stoma complications by Takahashi et al. [35] is almost the same as the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Classification, version 4.03 [36] concerning stoma prolapse, and this classification can be used as an indicator for the selection of treatment.

Severity grades 1 and 2

Conservative treatment is principally preferred for grade 1 (“no symptom; reducible prolapse”) and grade 2 (“recurrence after manual reduction; local irritation and stool leakage as stoma appliances are difficult to fit; and instrumental activities of daily living [ADL]”). In other words, in case of manageable stoma prolapse, devices for stoma appliances and the application of stoma appliances, manual reduction, and skin care are implemented [1, 37]. The use of gauze, change of body position [1, 37], and sugar application for stoma prolapse with severe edema [38, 39] have been described as useful methods for reducing stoma prolapse.

Severity grade 3

Grade 3 stoma prolapse exhibits “high-grade symptoms and the need for elective surgical treatment, with the restriction of ADL,” possibly indicating the need for surgery. Specifically, difficulty of stoma care, severe pain, and stoma injury by a stoma appliance are considered to be indications for surgery.

Severity grade 4

Grade 4 stoma prolapse occurs when “life-threatening medical conditions caused by the prolapse require emergent treatment (incarceration, etc.),” and emergent surgery is performed. Specifically, incarceration and ischemia of the stoma and obstruction of the intestine are indications for emergent surgery.

CLASSIFICATION OF SURGICAL TREATMENTS ACCORDING TO PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

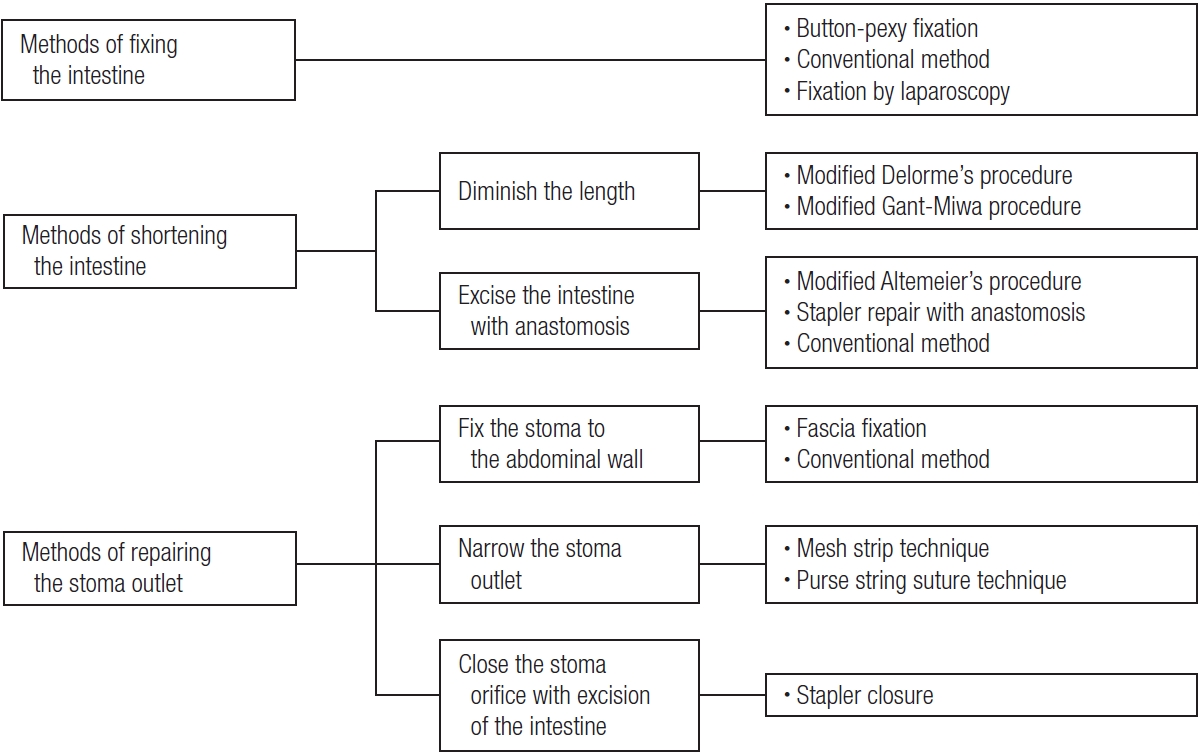

The pathophysiology of stoma prolapse includes mobile and redundant intestines, a gap between the stoma and the abdominal wall, and abdominal pressure, as previously described. Although the study that established those pathophysiological factors analyzed cases of loop colostomy [29], this pathophysiology can be applied to end stoma and ileostomy. Surgical treatment is performed to improve these factors. Maeda et al. [6] reported a classification of local repair for stoma prolapse. I herein propose a classification of all treatments for stoma prolapse by pathophysiology, including a laparoscopic fixation method (Fig. 2). For instance, there are methods of fixing the mobile intestine, methods of shortening the redundant intestine, and methods of repairing the stoma outlet to improve the gap between stoma and the abdominal wall (Fig. 2). Methods of fixing the mobile intestine include button-pexy fixation [40-43], techniques for suturing and fixing a stoma to the abdominal wall (conventional method) locally or by laparotomy [26], and laparoscopic fixation of a stoma to the abdominal wall [44] (Fig. 2). Methods of shortening the intestine include the modified Delorme procedure [45-47] and the modified Gant-Miwa procedure [48-50], performed only to diminish the length of the intestine. Other methods to shorten the intestine include excising the intestine with anastomosis, the modified Altemeier procedure [51, 52], stapler repair with anastomosis (procedure to perform excision and anastomosis by the stapler) [6, 53-61], and conventional methods by laparotomy [26]. As methods to repair the stoma outlet, fixing the stoma to the abdominal wall, fascia fixation [6] and conventional methods [26] have also been reported. Moreover, to narrow the stoma outlet, the mesh strip technique [62] and the purse-string suture technique [63, 64] have been reported. The choice between these 2 methods to narrow the stoma outlet depends on the operation site (the stoma orifice or skin level). Stapler closure, a method of closing the stoma orifice with excision of the prolapsed intestine using a stapler, prevents the inversion of the intestine for stoma prolapse. This procedure includes a method of shortening the intestine, but it was classified as a method of preparing the stoma outlet as it prevents the inversion of the intestine at the stoma outlet.

SELECTION OF SURGICAL TREATMENT

While many surgical methods have been reported, as classified in Fig. 2, most of these methods have been documented as case reports or cases with a limited number of participants. Therefore, there are no concrete criteria for selecting an appropriate treatment method for different cases [6]. Nonetheless, stoma closure may often be chosen at first instance as long as it is deemed surgically possible.

Local repair is a less invasive and safer procedure that can be used for patients with poor general conditions [6]. Laparoscopic repair is also a minimally invasive method but requires general anesthesia.

Invasive procedures such as repair and/or excision by laparotomy and stoma relocation have rarely been performed in recent years.

PRESENT STATE OF SURGICAL TREATMENTS

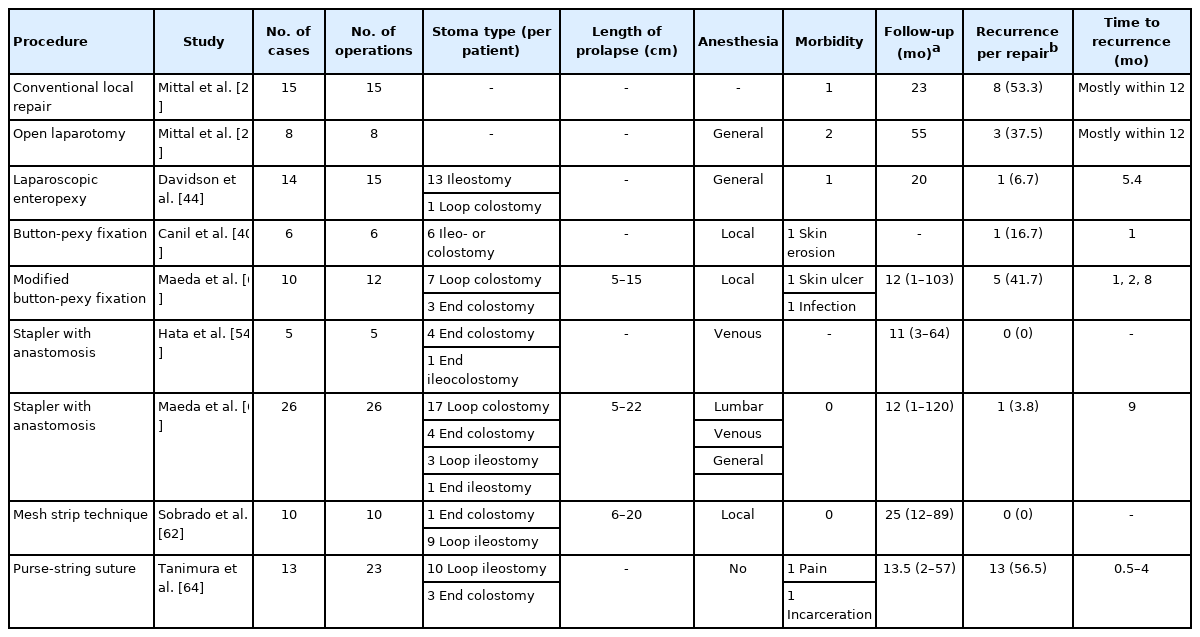

Reports with more than 5 cases are listed in Table 1, as most of the treatments mentioned later are from reports with a limited number of cases. The present state is described according to the classification of surgical treatment.

Methods of fixing the intestine

Button-pexy fixation

This method involves fixing the intestine to the abdominal wall by using 2 buttons located on the skin and within the intestine at the peristomal site [6, 40-43]. This is a simple treatment that is possible in the ward by using local anesthesia. Although Canil et al. [40] reported a recurrence rate of 16.7% (1 of 6 times), button-pexy fixation cannot be considered to be a method with a low recurrence rate, as our records showed a recurrence rate of 41.7% (5 of 12 times) (Table 1) [6]. Patients sometimes feel pain and experience slight bleeding from the intestine due to the movement of the intestine. Furthermore, complications such as skin erosion and ulceration have been observed. We no longer perform this method due to the above-mentioned reasons. This method can be used for terminal-stage cancer patients with stoma prolapse, as it is difficult to manage as a short-term treatment.

Conventional method

Fixation of the stoma to the abdominal wall has often been performed in combination with excision and anastomosis of the intestine after adhesion detachment. The recurrence rate ranged from 37.5% to 53.5% (Table 1) [26], even when performed by laparotomy or locally. The reason for this high recurrence rate remains unclear.

Fixation by laparoscopy

This method involves fixing the prolapsed-side intestine to the abdominal wall laparoscopically. Davidson et al. [44] performed this procedure in 14 cases, and 1 case needed reoperation due to intussusception after the initial surgery. They reported one recurrence of stoma prolapse (1 of 14 cases), corresponding to a 7% recurrence rate (Table 1). Thirteen of 14 cases performed had ileostomy prolapse. This laparoscopic procedure can be a better method for ileostomy prolapse, as stapler repair with anastomosis (discussed below) and methods of shortening the intestine may have limitations for repairing ileostomy prolapse [60]. However, general anesthesia is needed for this laparoscopic procedure; therefore, this method is not indicated for patients with poor general conditions.

Method of diminishing the length of intestine

Modified Delorme procedure

The Delorme procedure, which has been used for rectal prolapse, is a method of diminishing the length of the intestine by excising the mucosa with reefing the muscle layer for stoma prolapse. Limited cases of this method have been reported with some recurrence [45-47]. This procedure has a limitation in the length of intestine shortened; therefore, it is not suitable for long stoma prolapse [37].

Modified Gant-Miwa procedure

The Gant-Miwa procedure was originally developed as a transanal procedure for rectal prolapse [37]. This is a method of diminishing the length of the intestine by making knots after suturing the intestinal wall [48-50]. The recurrence rate is unclear as the number of cases is limited. However, the recurrence rate after rectal prolapse repair by this method has been reported to range from 0% to 31% [65]; thus, the same rate of recurrence can be speculated. This procedure is limited in terms of the length of intestine shortened, like the modified Delorme procedure; therefore, it is also not suitable for long stoma prolapse.

Methods of excising the intestine with anastomosis

Modified Altemeier procedure

This is a modified procedure used for rectal prolapse to excise the prolapsed intestine circumferentially and to perform hand-sewing end-to-end anastomosis. There is little information about recurrence due to limited case reports [51, 52]. The procedure requires attention to bleeding when performing hand sewing and preparation of vessels in the mesentery.

Stapler repair with anastomosis

This method involves excising and anastomosing the inner and outer prolapsed intestine simultaneously [53-61]. This has been a popular procedure with several devices including a stapler and appliances [54-61], after it was initially reported by Maeda et al. [53]. Venous or lumbar anesthesia is usually used. This procedure can be used for cases requiring defunctioning of the distal intestine in a transient loop stoma, as the continuity of the intestine can be maintained after excision of the prolapsed stoma. Excision with anastomosis can also be used for end stoma prolapse. The advantages of this procedure include no risk of bleeding, unlike the modified Altemeier procedure, shortened operative time, and the lowest rate of recurrence (0% to 3.8%) (Table 1) [6, 54]. A disadvantage is the cost of staplers.

Conventional method

The procedure is performed in combination with fixation of the intestine and the stoma around the stoma orifice, as described previously [26].

Method to fix the stoma to the abdominal wall

Fascia fixation is a procedure to diminish the space between the stoma and the abdominal wall by fixing the stoma to the fascia, similar to the conventional method. The recurrence rate is not low at 50.0% (2 of 4 cases), though the number of cases is limited. Therefore, this method is not considered sufficient to repair a stoma prolapse.

Methods to narrow the stoma outlet

1) Mesh strip technique

This procedure, a new day surgery reported in 2020, narrows the stoma outlet by putting polypropylene mesh around the stoma at the abdominal wall level under local anesthesia. Sobrado et al. [62] reported no recurrence in 10 cases undergoing this procedure during a median follow-up period of 25 months (Table 1). Exclusion criteria for this procedure include an American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status grade of II or more, defects in the main abdominal wall impacting this procedure, infections around the stoma, and stoma prolapse over 20 cm.

2) Purse-string suture technique

This procedure is performed to narrow the stoma orifice through a purse-string suture into the mucosa and the muscle layer with a 2-0 polypropylene string with a needle at the top of the stoma, after reduction of stoma prolapse [63, 64]. This procedure can be done without anesthesia. This is a modification of the Thiersch procedure for rectal prolapse. It was developed based on the theory of blocking the prolapse of the intestine, and it is usually performed for stoma prolapse that can be reduced manually [64]. Tanimura et al. [64] reported recurrence in 3 of 13 patients (23.1%) undergoing this procedure. They performed multiple procedures in several cases, and the total recurrence rate over time was 56.5% (13 of 23 times) (Table 1). In 1 case, a purse-string suture was taken out due to stoma incarceration after long-term follow-up [64]. This technique is advantageous in repairing prolapse without anesthesia for reducible stoma prolapse.

Method to close the stoma orifice with excision of the intestine by stapler

Stapler closure is indicated for prolapse of the distal limb of a loop stoma without the need for defunctioning the distal limb of the intestine [66]. This procedure is performed under venous or lumbar anesthesia. This method is especially useful in cases with incarcerated necrosis of stoma prolapse and can be accomplished easily and safely in a short amount of time [37]. This is a simple method, but it cannot be used in cases when loop stoma prolapse requires defunctioning of the distal limb of the intestine. The excision site of the intestine should be 1 to 2 cm above the skin level to avoid ischemia of the intestine at the skin side when performing stapler closure.

Methods to prevent stoma prolapse

Constructing a stoma in the following ways can prevent stoma prolapse: avoiding excessive incision of the fascia, fixing the stoma to the abdominal wall [29], selecting the site of the stoma in a way that prevents redundant intestine, and passing the intestine through the peritoneal route. Fixing the intraabdominal intestine or mesentery to the abdominal wall is an alternative [67], although a disadvantage of this method is the requirement of intestine dissection during stoma closure.

CONCLUSION

Prolapse of intestinal stoma is reviewed herein. Even though opportunities to observe patients with stomas usually decrease after surgery, it is important to stress the need for patients to understand stoma management through periodic outpatient clinic visits and to emphasize a team approach in accordance with the WOCN guideline.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

FUNDING

None.