Transvaginal removal of rectal stromal tumor with Martius flap interposition: a feasible option for a large tumor at the anterior wall of the rectum

Article information

Abstract

Neoadjuvant imatinib treatment, followed by complete transvaginal removal, presents a feasible option for large rectal gastrointestinal tumors located on the anterior wall of the rectum and protruding into the vagina. The use of Martius flap interposition is convenient and can be employed to prevent rectovaginal fistula.

INTRODUCTION

Rectal gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are relatively rare, accounting for approximately 5% of all GISTs [1, 2]. The clinical presentation of these tumors primarily depends on their size, the degree of mucosal invasion, and the presence of ulcers. Cases can range from being asymptomatic to displaying symptoms including rectal bleeding, pain, and rectal obstruction [1, 2].

Neoadjuvant imatinib may be utilized to reduce tumor size prior to surgery [3, 4]. The most effective treatment for resectable rectal GISTs is complete surgical resection. Various surgical options have been reported, such as low anterior resection and abdominoperineal resection (APR), either open or laparoscopic [5–7]. However, some smaller rectal GISTs located in the lower rectum can be feasibly excised either transanally or through transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) [8–11].

The surgical treatment of rectal GISTs that are situated in the anterior wall of the rectum or attached to the rectovaginal septum presents a challenge. This is due to their close proximity to the posterior wall of the vagina, which means that the removal of these tumors poses the risk of postoperative rectovaginal fistula.

We present the case of a 70-year-old woman with a large anterior rectal GIST. The patient was preoperatively treated with imatinib, and the tumor was subsequently removed successfully via a transvaginal approach.

TECHNIQUE

Ethics statement

Case briefing

A 70-year-old woman presented with reports of a sensation of rectal fullness that she had experienced for 3 months. The patient denied any history of rectal bleeding. A rectal examination revealed a submucosal mass on the anterior wall, located approximately 3 cm from the anal verge. Colonoscopy indicated a subepithelial mass in the lower rectum (Fig. 1). Endoscopic ultrasonography and biopsy were performed and revealed spindle cells with strongly positive staining for CD117 and CD34; this confirmed a diagnosis of rectal GIST. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) indicated a mass measuring 7.3 cm in diameter in the rectovaginal septum, situated 3 cm from the anal verge (Fig. 2). An abdominal and chest computed tomography scan revealed no distant metastasis. Given the size of the tumor and its proximity to the anal sphincter complex, a multidisciplinary team recommended neoadjuvant treatment with imatinib. The patient was administered 400 mg of imatinib daily for almost 2 years, as the surgical schedule was delayed due to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. The most recent MRI scan showed that the mass had shrunk to 5.4 cm in diameter (Fig. 2), and it remained stable at this size for 6 months.

Surgical technique

Following discussion within the multidisciplinary team, we concluded that the safest method for tumor removal was APR. This decision was based on the fact that the lower border of the tumor was attached to the upper part of the anal sphincter complex. However, the patient declined to proceed with APR. Consequently, we explored alternative procedures, including transanal operations such as TEM, transanal total mesorectal excision (taTME), laparoscopic or robotic approaches, and, notably, the transvaginal approach. The patient agreed to proceed with the transvaginal removal of the tumor. Accordingly, she was prepared for surgery with bowel preparation and preoperative antibiotics. Under general anesthesia, the patient was placed in the lithotomy position, and both vaginal and rectal examinations were performed to confirm resectability. A Lone Star Retractor was utilized (Fig. 3A). Then, the vaginal submucosa was injected with diluted epinephrine. Using electrocautery, the posterior wall of the vagina over the mass was elliptically incised on both sides to the length of the tumor. The proximal incision was extended to the perineum. Dissection was facilitated by an assistant’s placement of a finger in the rectum, which pushed the mass anteriorly (Fig. 3B). The tumor, which was found to originate from the anterior rectal wall, was removed en bloc with an intact pseudocapsule. The resulting rectal wall defect measured 2 cm in diameter and was closed with interrupted Maxon 3-0 sutures (Covidien), leaving a 2-cm rectal suture line. Subsequently, a 10-cm-long vertical incision was made over the left labia majora (Fig. 3C). Dissection was performed through this incision until the yellow fibrofatty pad of the left bulbocavernosus muscle was identified. This muscle was mobilized by dissection along its length from superior to inferior and both medial and lateral sides, while avoiding dissection on the posterolateral aspect of the inferior part of the muscle to preserve the blood supply from the pudendal artery. Once the desired flap length of 8 to 12 cm was achieved, the flap was divided at its superior margin with a right-angle clamp, followed by division and suture ligation with absorbable 3-0 sutures. This left a 1.5- to 2-cm-wide, inferior-based vascular flap. A subcutaneous tunnel was created from the left labia majora wound to the surgical site using blunt dissection with fingers and a clamp, with the tunnel wide enough to admit at least 2 fingers to avoid compressing the blood supply of the flap (Fig. 3D). The left bulbocavernosus muscle flap was passed through the subcutaneous tunnel and fixed 1.5 cm beyond the superior margin of the rectal suture lines with 3 interrupted Maxon 3-0 sutures. Both lateral sides of the flap were again sutured using 4 to 6 interrupted Maxon 3-0 sutures to secure the flap along the length of the rectal suture line and prevent migration (Fig. 3E). The posterior vaginal defect was repaired with interrupted Vicryl 3-0 sutures (Ethicon Inc) over the Martius flap. The left labia majora wound was closed with a small suction drainage catheter using subcuticular stitches (Fig. 3F). The total operative time was 2 hours and 48 minutes, with minimal blood loss.

The surgical procedure of transvaginal removal. (A) An elliptical incision was made on both sides of the posterior vaginal wall. (B) The lesion was made to protrude anteriorly via an assistant’s placement of a finger in the rectum. (C) The left bulbocavernosus muscle was dissected. (D) A tunnel was established for the flap. (E) A Martius flap was sutured over the rectal wound. (F) The immediate postoperative results are shown.

Results

The immediate postoperative period proceeded without complications. The patient was instructed to abstain from oral intake for 5 days before resuming her diet. She was discharged from the hospital on the 7th day following the operation.

The final pathology report revealed a rectal GIST measuring 5.5×5.0×4.0 cm, along with an attached vaginal mucosal surface measuring 5×1 cm (Fig. 4). The cut surface exhibited an inhomogeneous tan-brown appearance, with some areas showing signs of hemorrhage. Histopathological analysis did not reveal any residual tumor cells, indicating a complete response to the preoperative treatment. At the patient’s most recent follow-up visit, 1 year postsurgery, she had recovered well and exhibited no tumor recurrence.

DISCUSSION

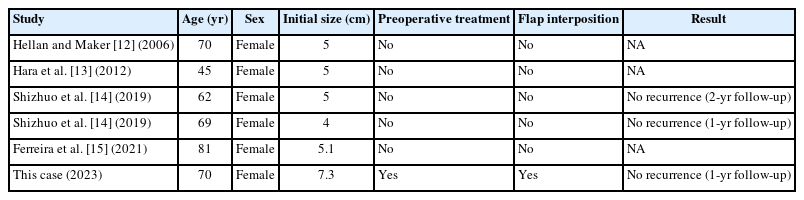

Complete resection with a free margin is key to preventing recurrence [1–4]. The selection of surgical procedures for rectal GIST is variable, depending on the size, location, and extent of invasion into adjacent organs [5, 9]. For large GISTs in the lower rectum with involvement of the sphincter complex, the preferred operation may be APR. However, this procedure may negatively impact the patient’s quality of life due to the lifelong requirement for a colostomy. An alternative surgical procedure for small GISTs located in the lower rectum is transanal removal, with or without TEM, taTME, laparoscopic surgery, or robotic surgery. However, the limited space within the rectum often prevents the safe removal of large rectal tumors without breaching the pseudocapsule, particularly when the tumor’s size exceeds the normal diameter of the rectum (3 cm). Preoperative imatinib may be considered for large rectal GISTs located in the lower rectum to induce tumor shrinkage and facilitate local resection [3, 6, 8, 10]. TEM is a viable alternative for rectal stromal tumors smaller than 3 cm and located in the mid to upper rectum. A feasible option for rectal stromal tumors located on the posterior wall and extending into the perirectal fat may be taTME. Laparoscopic or robotic removal of rectal stromal tumors in the lower rectum is challenging due to the difficulty of deep pelvic dissection without tactile sensation; thus, the risk of breaking the tumor pseudocapsule is often substantial, depending on the surgeon’s expertise. Transvaginal removal of rectal stromal tumors on the anterior wall is an intriguing option for anteriorly located rectal stromal tumors, especially when their growth causes the tumor to protrude into the posterior vaginal wall. Very few publications have reported transvaginal removal of rectal GISTs (Table 1) [12–15]. Hellan and Maker [12] reported in 2006 that transvaginal excision of a 5-cm rectal stromal tumor was a safe alternative, eliminating the need for an unnecessary APR. In 2009, Shizhuo et al. [14] also reported 2 cases of rectal GISTs (4 cm and 5 cm) that were safely resected transvaginally. More recently, in 2021, Ferreira et al. [15] used transvaginal resection for a 5-cm rectal GIST and considered it an acceptable procedure for lesions located in the rectovaginal septum. None of the previous case reports involved preoperative treatment like that in the present report. This can be attributed to the larger initial size of the tumor in our patient (7.3 cm).

In the present case, we employed a transvaginal approach to remove an anterior rectal GIST, with 3 notable aspects of the procedure. First, we made 2 elliptical vaginal incisions along the sides of the mass to reduce the dissection time. Second, the assistant’s finger was used to apply anterior pressure in the rectum, which facilitated the establishment of tension and a surgical plane during the dissection. Third, we performed a Martius flap interposition between the vaginal and rectal suture lines to promote the healing of both wounds without complications. This type of flap is advantageous due to its ease of creation and its convenient location in relation to the operative field.

In conclusion, rectal GIST is a rare but curable disease. Neoadjuvant treatment for rectal GIST in the lower rectum can shrink the tumor, facilitating safe surgical removal. For suitable patients, the transvaginal removal of anterior rectal GIST constitutes a viable alternative method. The use of Martius flap reinforcement can help prevent the occurrence of rectovaginal fistula after surgery.

Notes

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

None.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: WS, PK; Methodology: all authors; Investigation: all authors; Writing-original draft: WS, PK; Writing-review & editing: all authors. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.