Clinical Etiology of Hypermetabolic Pelvic Lesions in Postoperative Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography for Patients With Rectal and Sigmoid Cancer

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to present various clinical etiologies of hypermetabolic pelvic lesions on postoperative positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) images for patients with rectal and sigmoid cancer.

Methods

Postoperative PET/CT images for patients with rectal and sigmoid cancer were retrospectively reviewed to identify hypermetabolic pelvic lesions. Positive findings were detected in 70 PET/CT images from 45 patients; 2 patients who were lost to follow-up were excluded. All PET findings were analyzed in comparison with contrast-enhanced CT.

Results

A total of 43 patients were classified into 2 groups: patients with a malignancy including local recurrence (n = 30) and patients with other benign lesions (n = 13). Malignant lesions such as a local recurrent tumor, peritoneal carcinomatosis, and incidental uterine malignancy, as well as various benign lesions such as an anastomotic sinus, fistula, abscess, reactive lymph node, and normal ovary, were observed.

Conclusion

PET/CT performed during postoperative surveillance of rectal and sigmoid colon cancer showed increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake not only in local recurrence, but also in benign pelvic etiologies. Therefore, physicians need to be cautious about the broad clinical spectrum of hypermetabolic pelvic lesions when interpreting images.

INTRODUCTION

Despite the progress in surgical and adjuvant therapeutic modalities in the treatment of patients with colorectal cancer, metastasis or local recurrence occurs in 30%–50% of all patients within 2 years of surgery. Pelvic recurrence occurs in as many as 30% of all cases [1]. Radiologic tools, such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are used to detect recurrence, and more recently, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography/CT (PET/CT) has shown excellent diagnostic performance in the detection of local recurrence and metastasis in patients with colorectal cancer. However, PET images show increased FDG uptake not only in locally recurrent malignancies and metastases but also for other conditions, such as inflammation [2, 3]. In this study, we present the clinical etiology of hypermetabolic pelvic lesions in postoperative PET/CT images of patients with rectal and sigmoid colon cancer.

METHODS

Postoperative PET/CT and contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) images for patients with rectal and sigmoid cancer who had undergone an anterior resection or a lower anterior resection between January 2011 and April 2015 were reviewed retrospectively to identify hypermetabolic pelvic lesions. A total of 894 PET/CT procedures were performed for restaging, therapeutic response monitoring, or postoperative surveillance in 410 patients. The median time interval between PET/CT and surgery was 36 months (range, 1.5–184 months). Positive findings were detected in 70 PET/CT images from 45 patients, and all PET findings were analyzed in comparison with CECT findings.

All 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging was performed on a Discovery 690 PET/CT scanner (GE Medical System, Waukesha, WI, USA). Blood glucose levels before scanning were checked and were <180 mg/dL. PET/CT images were acquired 1 hour after injection of 5.55 MBq of FDG per kg body weight. A helical nonenhanced CT scan was performed from the top of the skull base to the midthigh with normal breathing. Immediately after CT, PET was performed covering the same axial-field views of the body. PET emission data were acquired at 2 minutes per bed position. PET images were generated using standard 3-dimensional VUE point FX (VPFX, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) time-of-flight reconstruction algorithms with CT-based attenuation correction. CECT scans were performed using two multidetector CT scanners (SOMATOM Definition and SOMATOM Definition AS+, Siemens Medical Solution, Forchheim, Germany) with contrast enhancement (Optiray, Guerbet).

Two nuclear medicine physicians and a radiologist independently reviewed the PET/CT and CECT images, respectively. We opted to use visual inspection rather than an absolute standardized uptake value to define a hypermetabolic focus. Pelvic recurrence was classified according to the location of the lesion [4].

As it is a retrospective study that does not collect personally identifiable information, it is subject to an exemption from IRB review.

RESULTS

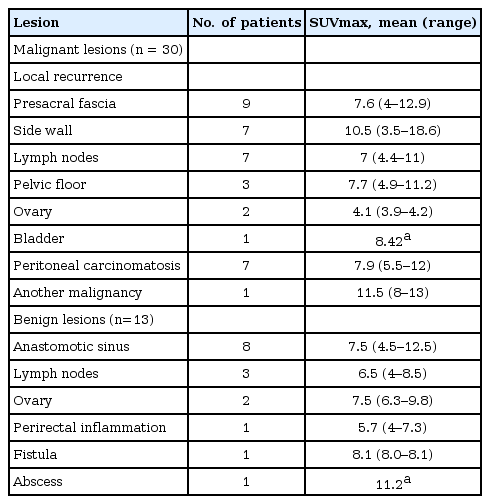

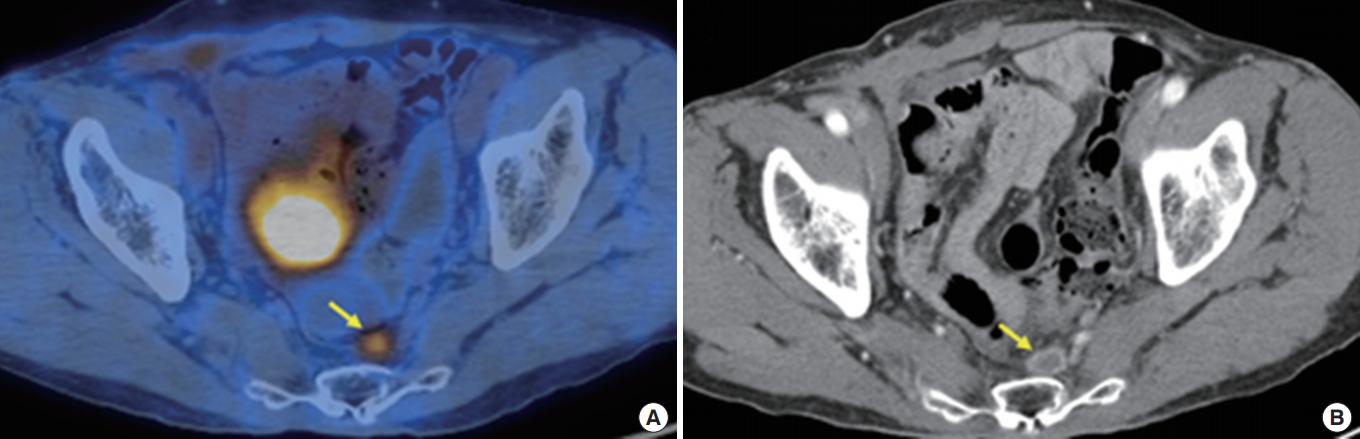

Forty-five of the 410 patients (11%) had hypermetabolic pelvic lesions on PET/CT imaging. Four recurrent lesions and 6 benign lesions were confirmed by surgery or biopsy. Other lesions were confirmed by further imaging studies (CECT, MRI) and at least 12 months of clinical follow-up. Two patients who were lost to follow-up were excluded. Thus, data from 43 patients were included in this study. The histologic subtype was an adenocarcinoma in all 43 patients: rectal cancer (n = 34), rectosigmoid colon cancer (n = 5), and sigmoid colon cancer (n = 4). These patients (27 male, 16 female patients; age range, 35–95 years; mean age, 63.1 ± 12.9 years) were classified into 2 groups: patients with malignant lesions (n = 30) including local recurrence (Figs. 1–3), and patients with other benign lesions (n = 13). Recurrence (n = 23, 5.6%) was classified according to Sinaei et al. [4] by using lesion location. These results are detailed in Table 1. Demographic and clinicopathologic features are described in Table 2.

A 63-year-old male had undergone a laparoscopic low anterior resection due to rectal cancer 1 year earlier. (A) A recurrent tumor in the left pelvic side wall was detected in the positron emission tomography/computed tomography (CT) fusion image as increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the tumor (arrow) and (B) presented as an enhancing tumor (arrow) in the contrast-enhanced CT image.

A 71-year-old male had undergone a laparoscopic low anterior resection due to rectal cancer 3 years earlier. (A) A recurrent tumor (arrow) with increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the presacral fascia was detected in the positron emission tomography/computed tomography (CT) fusion image. (B) The lesion was seen as a peripheral enhancing tumor (arrow) in the contrast-enhanced CT image.

A 41-year-old female had undergone a laparoscopic anterior resection due to sigmoid colon cancer 1 year earlier. (A) A multilocular cystic mass in the right ovary with increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake at the solid portion of the tumor (arrow) was identified in the positron emission tomography/computed tomography (CT) fusion image and (B) presented as a solid, cystic tumor with multiple enhancing septa (arrow) in the contrast-enhanced CT image. Following surgical resection, pathology confirmed ovarian metastasis.

DISCUSSION

Local recurrence of colorectal cancer after resection is associated with serious morbidity and mortality, and early detection at an operable stage is crucial [1]. According to a study by Tagliacozzo and Accordino [5], pelvic recurrence after surgical treatment of patients with rectal and sigmoid cancer occurred in 16% of those patients, and 80% of those recurrences occurred within 2 years of the surgery. For the detection of such recurrences, several diagnostic tools, such as hemoglobin and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) testing, CT, MRI, endoscopic ultrasound, endoscopy, PET, etc., are used [2, 6].

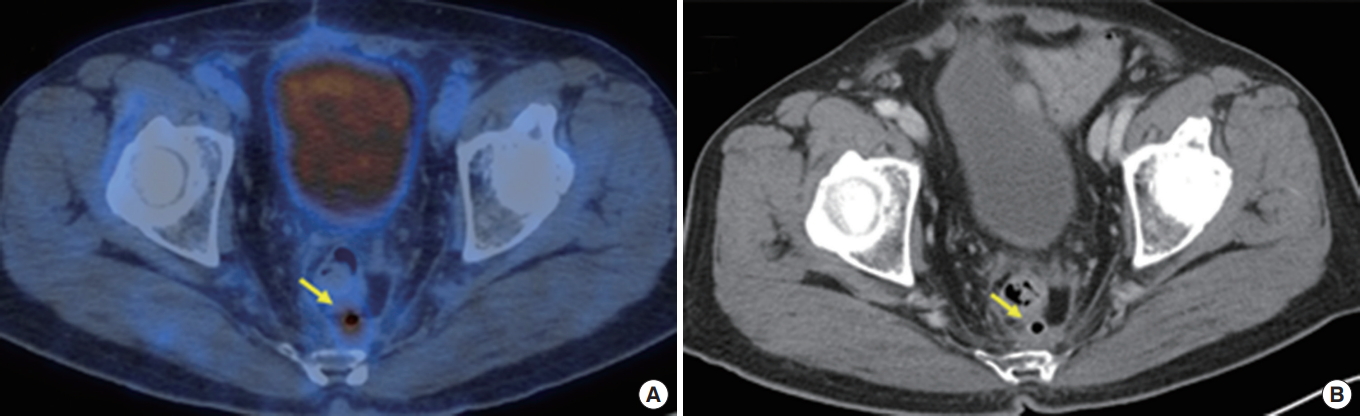

The reported accuracy of FDG PET for detecting pelvic recurrences of colorectal cancer ranges from 74% to 96% [7]. Makis et al. [8] reported that PET/CT was superior to serum CEA for the detection of recurrences. Fiocchi et al. [2] reported that PET/CT showed a high sensitivity of 94.4% for the evaluation of patients with suspected local recurrence of colorectal cancer. In our study, in addition to local recurrences, other malignant lesions, such as peritoneal carcinomatosis (n = 7) and an incidental uterine carcinoma (n = 1), showed increased FDG uptake. Although PET is regarded as being highly sensitive, it shows increased FDG uptake in other benign conditions, such as inflammation; it can also show physiologic uptake in muscle, fat, and bowel tissue [2, 9]. In our study, 13 patients showed a variety of hypermetabolic, benign etiologies. An anastomotic sinus was detected in 8 patients, and benign reactive lymph nodes, normal ovaries, perirectal inflammations, perianal fistulae, and abscesses were detected in others (Figs. 4, 5).

A 72-year-old male had undergone a laparoscopic anterior resection due to rectal cancer 1 year earlier. (A) Hypermetabolism at the presacral anastomotic sinus (arrow) was shown in the positron emission tomography/computed tomography (CT) fusion image, and (B) an air-containing sinus (arrow) with adjacent fibrosis was shown in the contrast-enhanced CT image.

A 58-year-old male had undergone a laparoscopic low anterior resection due to rectal cancer 4 years earlier. (A) A fistula tract (arrow) in the posterolateral aspect of the anus was observed in the positron emission tomography/computed tomography (CT) fusion image, and (B) an enhancing fistula tract (arrow) was shown in the contrast-enhanced CT image.

Anastomotic leakage as a postsurgical complication after bowel resection surgery can eventually evolve into a presacral sinus, fistula, and/or abscess [10]. To our knowledge, no study has addressed the PET/CT findings for an anastomotic sinus or fistula. The mechanism of FDG uptake is uncertain in patients with an anastomotic leakage, but it may be due to the inflammatory processes associated with this complication [11]. In prospective studies, Lerman et al. [12] and Nishizawa et al. [13] reported physiological ovarian FDG uptake in premenopausal women during the ovulation phase of the menstrual cycle. Thus, a differential diagnosis of normal ovaries and malignant ovarian lesions based only on hypermetabolism is problematic [12, 13]. Therefore, other imaging studies or a clinical interview about the menstrual cycle will be needed when diagnosing hypermetabolic ovarian lesions [13].

In our study, we obtained CECT images as a way to obtain further anatomical and morphological information, which provided the pattern of contrast enhancement and lesion characterization and allowed differentiation of benign hypermetabolic lesions from malignancy and accurate diagnosis of pathology. Detailed comparisons to the anatomical and the morphological structures on the CECT images, in addition to those on the nonenhanced PET/CT images, should assist in the accurate identification of hypermetabolic pelvic lesions on PET images.

Our study has several limitations. First, the selected population included only patients with rectal and sigmoid cancer who underwent PET/CT for postoperative surveillance imaging. Second, the presence of recurrence with no FDG uptake should be considered. Negative PET/CT findings have been reported in patients with histologically mucinous adenocarcinomas [8, 14].

In conclusion, PET/CT for postoperative surveillance of patients with rectal and sigmoid colon cancer shows increased FDG uptake not only in areas of local recurrence but also in various categories of benign pelvic lesions. Physicians should be cautious and consider the broad clinical spectrum of possibilities when interpreting such images.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.