Clinical trial of combining botulinum toxin injection and fissurectomy for chronic anal fissure: a dose-dependent study

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

Our aim was to evaluate the effectiveness of combining fissurectomy with botulinum toxin A injection in treating chronic anal fissures.

Methods

A single surgeon in Saudi Arabia conducted a nonrandomized prospective cohort study between October 2015 and July 2020. The cohort included 116 female patients with chronic anal fissures, with a mean age of 36.57±11.52 years, who presented to the surgical outpatient clinic and received a botulinum toxin injection combined with fissurectomy. They were followed up with at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 8 weeks to evaluate the effects of the treatment, then again at 1 year. The primary outcome measures were symptomatic relief, complications, recurrence, and the need for further surgical intervention.

Results

Treatment with botulinum toxin A combined with fissurectomy was effective in 99.1% of patients with chronic anal fissures at 1 year. Five patients experienced recurrence at 8 weeks, which resolved completely with a pharmacological sphincterotomy. Twelve patients experienced minor incontinence, which later disappeared. Pain completely disappeared in more than half of the patients (55.2%) within 7 to 14 days. Pain started to improve in less than 8 days among patients treated with a dose of 50±10 IU (P=0.002).

Conclusion

Seventy units of botulinum toxin A injection combined with a fissurectomy is a suitable second-line treatment of choice for chronic anal fissures, with a high degree of success and low rate of major morbidity.

INTRODUCTION

Anal fissures, in which spasms of the internal anal sphincter play a major role, constitute a common surgical disease. It is usually treated conservatively. The gold-standard surgical treatment is a lateral internal sphincterotomy, but this procedure carries the potential risk of developing postoperative complications in the form of gas or stool incontinence [1, 2]. Therefore, another treatment was recently introduced: botulinum toxin A (BTA) injection in conjunction with fissurectomy [3, 4]. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the efficacy of combined treatment involving BTA injection and fissurectomy for treating chronic anal fissures. We subdivided patients into 3 different groups depending on the BTA dose received (50, 70, or 100 units), which was chosen according to the subjective feeling of sphincter tightness.

METHODS

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of King Saud University Medical City (No. IRB-kl983750) and by the Public Institutional Review Board of the Ministry of Health of Saudi Arabia (No. 493875097). Participation was voluntary, and all participants provided informed consent after receiving a full description of the research.

Study design

This case series is a prospective study (involving a nonrandomized simple sample). A total of 116 patients who presented to the surgical outpatient clinic of King Saud University Medical City (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia) with anal fissures between October 2015 and July 2020 were enrolled. The inclusion criteria consisted of all patients with evidence of a posterior or anterior fissure with clinical evidence of an increase in anal resting tone according to a physical exam. We excluded pediatric patients and all female patients who were at high risk of problems, particularly after obstetric operations and deliveries; also, these female patients’ sphincters and muscle tone were very weak, and they were therefore unable to tolerate surgery. This could also affect their healing and muscle tone later. Persistent symptoms included pain and bleeding after defecation for more than 8 weeks despite conservative treatment. Other exclusion criteria included patients with anal abscesses or fistulas; those with fissures associated with different pathologies such as inflammatory bowel disease, concomitant medication that could interfere with BTA such as aminoglycosides, baclofen, or diazepam; and pregnancy.

The study’s endpoint was complete healing after BTA injection combined with fissurectomy, and the study compared dose-dependent efficacy and complications among doses of 50, 70, and 100 units. The treatment was considered successful if the patient experienced an absence of symptoms. A secondary variable was the latency of the effect, which was defined by considering the time interval between the day of treatment and the start of symptomatic relief during follow-up, and the rate of incontinence and time of resolution (days), linked to different doses of BTA (50 units vs. 70 units vs. 100 units).

Baseline assessment and operative technique

All patients underwent a pre-treatment evaluation, including a clinical examination. Each patient received conservative treatment (sitz bath, stool softener, and pharmacological treatment [diltiazem]), and underwent the same evaluation as performed at baseline. One surgeon (NA) operated on all of the patients.

The procedure was performed as a day-case, under laryngeal mask anesthesia, with the patient lying in the lithotomy position. One hundred units of botulinum neurotoxin A (BoNT/A; Botox, Allergan) were diluted with 1 mL of normal saline. The solution was injected into the internal anal sphincter using a small 27-gauge needle. The injection was divided in half, as is standard; half of the amount was administered between 3 and 9 o’clock, and the other half was administered either at or around the fissure. However, the amount of BoNT varied, as patients received 50, 70, or 100 units. Fissurectomy was performed in each patient using a surgical blade, which involved the precise removal of fibrotic fissure edges and unhealthy granulation tissue at the base.

Clinical care, follow‐up, and outcome measures

All patients were sent home on laxatives and oral analgesia within 24 hours of the procedure. Patients were advised to take regular warm sitz baths, maintain a high-fiber diet, and increase their fluid intake.

All patients were evaluated in the outpatient clinic at approximately 7, 14, 21, and 28 days, and at 8 weeks postoperatively. Symptoms were reviewed in terms of pain (degree of improvement and onset of improvement), per rectal bleeding, and the presence of incontinence (gas, liquid, or stool). The patients were followed up for 1 year, during which time they underwent historical and physical examinations.

Statistical analysis

A statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS ver. 26.0 (IBM Corp), where descriptive and frequency analyses were carried out first. Some of the continuous variables, such as age, were recorded as categorical variables for a chi-square analysis, in which several groups’ relationships are tested under a 95% confidence interval. The null hypothesis was rejected if the P-value obtained from the chi-square analysis was greater than the cutoff α level of 0.05.

RESULTS

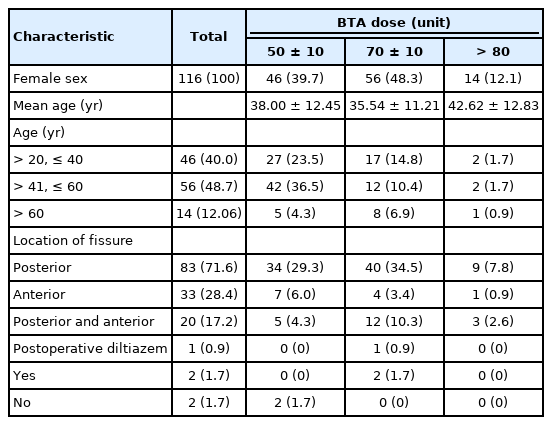

The BoNT/A dose units were divided into 3 categories: 50±10, 70±10, and 100 units. As shown in Table 1, the participants whose dose was greater than 80 units were older. An analysis of the categorical data further reveals that those in the group between 41 and 60 years of age who also received 40 to 60 units of BoNT/A (n=42, 36.5%), while the group above 60 years who also received BTA doses greater than 80 units had the lowest frequency (n=1, 0.9%). Cross-tabulation between the location of the fissure and the BoNT/A units indicated that the largest group comprised patients with a posterior fissure who also received between 61 and 80 units of BoNT/A (n=40, 34.5%), while the smallest group consistent of patients with an anterior fissure who also received more than 80 units of BTA (n=1, 0.9%).

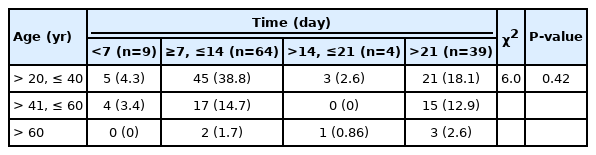

Table 2 shows a summary of the chi-square analysis conducted between the age categories and the time of symptom resolution. The P-value obtained from the analysis, 0.42, is greater than the critical α level of 0.05. Hence, the null hypothesis that there was no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups was accepted. There was no relationship between the time of symptom resolution and the patient’s age.

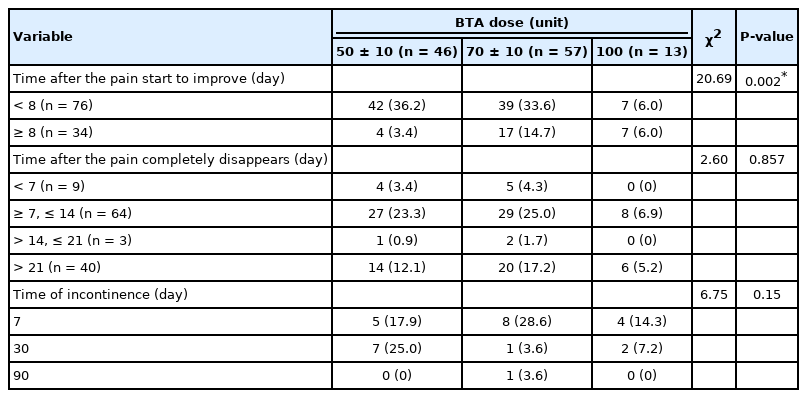

Table 3 shows a summary of the relationship between the BoNT/A dose and the time the pain started to improve—that is, the time it took for the symptoms to disappear entirely, along with the duration of incontinence. Based on the results, the number of days until the pain started to improve was separated into 2 categories: less than 8 days and more than or equal to 8 days. The obtained P-value from the chi-square analysis, 0.002, was less than the critical α of 0.05. In essence, the number of days until the pain started to improve was dependent on the number of BoNT/A units administered. The number of days after the pain completely disappeared was divided into 4 categories: <7 days (n=9), 7 to 14 days (n=68), >14 to 21 days (n=10), and >21 days (n=28). The obtained P-value, 0.857, was greater than the critical α level of 0.05. Hence, there was no relationship between the number of days after the pain completely disappeared and the number of BoNT/A units administered. For the duration of incontinence, the obtained P-value of 0.15 revealed no significant relationship with the amount of BoNT/A units administered.

The number of days after which the pain completely disappeared was also divided into 4 categories. The results indicate that the largest group (n=60, 55.2%) took between 8 and 14 days for the pain to completely disappear, while the second group (n=40, 34.5%) took more than 21 days. The remaining results were as follows: <7 days, 7.8%; 7 to 14 days, 55.2%; >14 to 21 days, 2.6%; and >21 days, 34.5%.

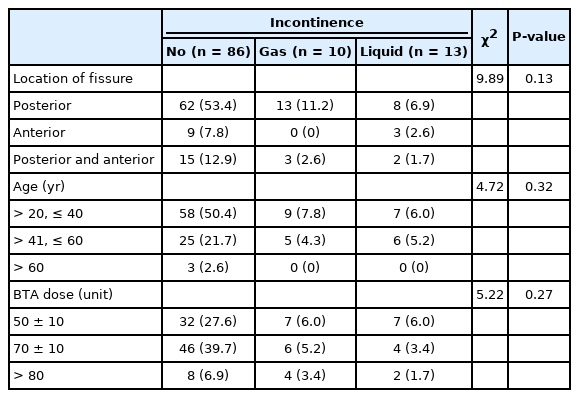

Table 4 summarizes the results of chi-square analysis between incontinence and location of the fissure, age, and BoNT/A dose. All of the obtained P-values were greater than the critical α level of 0.05. Hence, there was a statistically significant relationship between incontinence and location of the fissure, age, and BoNT/A dose.

DISCUSSION

The treatment of anal fissures was inconsistent until 1951 when Eisenhammer proposed using a partial lateral internal sphincterotomy. It is considered the standard treatment for anal fissures [5]. However, owing to the noticeable risk of permanent fecal incontinence (1% of patients), which may occur many years after if the sphincter is exposed to further damage, such as a complicated delivery or anal surgery, alternative treatments have been sought [6].

Since BTA injection was introduced as a potential treatment for anal fissures in 1993, there have been several studies that proved its efficacy, with a varying healing rate and recurrent rate [6–8]. BTA works by inhibiting acetylcholine release into the internal sphincter close to an anal fissure [7]; however, a fissurectomy alone is advocated for in children and adults in some areas [9]. This procedure enhances healing by removing the fibrotic fissure edges; nevertheless, it does not address the anal sphincter hypertonicity. A study reported that combining fissurectomy and BTA injection achieved an excellent healing rate of 79% after 1 year [10].

We decided to conduct a study of all female patients, since they have a higher rate of incontinence [11] resulting from risk factors during pregnancy and childbirth. Eighty-four of our patients (72.4%) displayed posterior fissures and 15 patients (12.9%) had anterior fissures. This is consistent with what has been reported in the literature, in which 90% of all fissures occurred posteriorly, 10% anteriorly, and fewer than 1% of patients had both anterior and posterior fissures [12–14]. However, we had a higher number of patients (n=17) who had both anterior and posterior fissures than reported in the literature.

In comparison with Barnes et al. [15], who used a similar technique of combining fissurectomy and BoNT/A, our study has a larger number of patients. We were able to achieve an overall healing rate of 99.1% at 1 year without resorting to surgical sphincterotomy. There was only one recurrence during 1 year of follow-up, a figure slightly more favorable compared to Barnes et al. [15]. It is noteworthy to recognize that they administered 100 units to all patients, using a technique where they injected BoNT/A into the base of the fissure, whereas we injected half of the amount at the fissure and the other half at 3 and 9 o’clock. We believe this relaxes the whole sphincter, which could contribute to a higher success rate.

There is considerable variation in the literature regarding the most effective site of BTA injection. Our technique is similar to what was reported in a previous study that used only 25 units and reported a healing rate of 81.8% after BoNT/A injection [16]. In comparison to our data, injecting patients with a higher dose of BoNT/A (i.e., 100 units) failed to exhibit superior results in terms of shortening the time for symptoms’ resolution or the onset when compared to 50 or 70 units, where all cases took place at >7 days (87.0% vs. 83.9% vs. 85.7% for the 50-, 70-, and 100-units BoNT/A groups, respectively). It is also noteworthy that there was a higher incidence of liquid incontinence in the group that received 100 units. Our study reported a 10.3% rate of incontinence in the immediate postoperative period. This appears to be above the upper limit of the range reported (4%–7%) in previous studies [5, 14, 17], which can likely be attributed to the technique of injecting at 3 areas. However, the incontinence was transient, and all patients reported normal continence by the 8-week follow-up.

In our data, when we compared the 3 groups (50, 70, and 100 units), superior results were found when 70 units were used, with complete resolution of symptoms in 76.7% of patients in 7 to 14 days and no incontinence in 82.1,% even though the meta-analysis conducted by Bobkiewicz et al. [18] claimed no dose-dependent pattern of efficiency.

In our experience, we likely had more success because all our patients were women. Soltany et al. [16] reported superior results in female patients. Our results compare favorably with published data. Most of the enrolled patients (94.8%) experienced symptom resolution and complete healing of the fissure(s). Only one recurrence occurred after achieving complete healing, and this particular patient revealed later that she did not comply with conservative therapy or good eating habits.

There were 5 recurrences in a mean follow-up period of 8 weeks. These were completely resolved by using diltiazem.

In conclusion, 70 units of BTA injection combined with fissurectomy is a suitable second-line treatment for chronic idiopathic anal fissures that are not associated with other anal conditions. Due to the high degree of success and low rate of major morbidity, the procedure may be considered as a straightforward, safe, and effective treatment for anal fissures.

Notes

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

None.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: NA; Data curation: NA; Formal analysis: AIA, GAA; Investigation: AIA, GAA; Methodology: NA; Project administration: AIA, GAA; Resources: all authors; Software: NA; Supervision: NA; Validation: all authors; Visualization: NA; Writing–original draft: all authors; Writing–review & editing: all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.