INTRODUCTION

Pruritus ani is an unpleasant cutaneous sensation, and its symptoms are characterized by varying degrees of itching around the anal orifice [1]. Pruritus ani is a common proctological problem, and many physicians believe that it reflects hemorrhoidal disease. The exact incidence worldwide is unknown, but men are affected more often than women by a ratio of 4:1. Most patients are distributed in the 30-70 age group and it is particularly prevalent in the 40-60 age group [2, 3]. This article addresses the etiology of pruritus ani, its underlying disease, and current medical treatments for pruritus ani.

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Pruritus ani may have various causes, and it has been divided into two subtypes: idiopathic and secondary. Idiopathic pruritus ani accounts for 25-75% of pruritus ani cases depending on investigators, and it is diagnosed in cases in which no etiology can be found. Secondary pruritus ani is diagnosed when an underlying cause can be identified and treatment leads to an improvement in the pruritus ani [4].

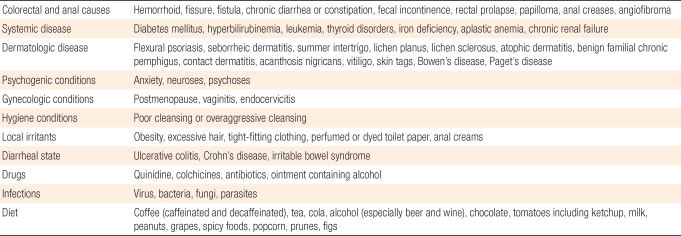

There exists a long list of specific disease entities that may cause pruritus ani, and these are usually categorized into infectious and non-infectious causes. The most prevalent anorectal diseases related with pruritus ani are hemorrhoids and anal fissures; others are anal fistulas, abscesses, proctitis, rectal cancer, adenomatous polyps, etc. Skin disorders as etiologic factor are contact dermatitis, lichen planus, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, vitiligo, squamous cell carcinomas, Paget's disease, etc. Infectious disease, such as infections due to bacteria and fungus, should not be overlooked [5]. Fungal infections have been reported to account for up to 15% of the underlying causes of pruritus ani, and other infections, such as those due to viruses, parasites (pinworms), etc., are also causes of pruritus ani. Medications, such as tetracycline, colchcine, quinidine, local anesthetics, neomycin, etc., and systemic diseases, such as diabetes, lymphoma, obstructive jaundice, thyroid dysfunction, leukemia, chronic renal failure, and aplastic anemia, are considered as causative factors. Some studies have reported that pruritus ani was reduced within 2 weeks after avoiding specific foods, such as tomatoes, chocolate, citric fruits, spices, coffee (including both caffeinated and decaffeinated), tea, cola, beer, milk and other dairy products [4, 6, 7]. Psychological factors, such as anxiety, agitation, and stress, may also cause pruritus ani [8]. Others are fecal incontinence, excessive humidity, the use of soap, excess scrubbing of the anus, chronic diarrhea, and menopause (Table 1).

The pathophysiology of pruritus ani has not been elucidated yet. It has been hypothesized that when sensory nerves in the perianal area are stimulated, skin irritation and subsequent pruritis is induced; consequently, the skin is excessively scratched, which causes skin injury. Fecal contamination due to abnormal transient internal sphincter relaxation has also been reported to result in a subsequent perianal itching problem. Feces contain endopeptidases of bacterial origin, in addition to potential allergens and bacteria. These enzymes are capable of causing both itching and inflammation.

SYMPTOMS AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The main symptom of pruritus ani is the untolerable impulse to scratch the perianal area. Although that symptom can occur at any time, it is most common following a bowel movement, especially after liquid stools, and at bedtime, just before falling asleep. Some patients also experience intense itching during the night. As the area of involvement spreads and the intensity of itching increases, the patients reflexively begin scratching and clawing at the skin. This leads to further skin damage, excoriation, and potentially a secondary skin infection.

Gordon classified pruritus ani into three clinical stages according to the skin condition. In stage 0, the skin appears normal. In stage 1, the skin is red and inflamed. In stage 2, the patient presents with white lichenified skin. In stage 3, the patient presents with lichenified skin, as well as coarse ridges of skin and often ulcerations secondary to scratching. The skin lesions of pruritus ani caused by food often have symmetric shapes.

A carefully taken history can often aid in identifying the cause of pruritus. This history should include any change in bowel habit and details of any other previous or current dermatological or gastrointestinal problems. Clinicians should ask patients about the onset of symptoms and the relationship of the onset to diet, medication and anal hygiene practices. Pruritus ani can be caused by infestation with enterobius vermicularis, or pinworms, especially in children. The worms emerge from the anal canal at night and early morning; thus, pruritus is worst at those times. Sticky-tape tests should be performed for identifying the eggs or adult worms microscopically. Pruritus ani may develop due to gynecological causes in female patients; thus, pruritus on the perineal region caused by vaginal discharge or urinary incontinence should be considered. Infectious diseases, such as cervicitis, trichomoniasis and candidiasis, should be considered. Although rare, for postmenopausal women showing atrophic vaginitis findings, together with hot flushes due to hormonal changes, symptoms may be ameliorated by hormone replacement therapy.

At the visual inspection, maceration, erythema, desquamation or lichenification of the skin may be observed, and to assess the secondary causes of pruritus, which can be inferred from abnormalities of the sphincter and from the history of disease, digital rectal examination and anoscopic examination should be performed. Gayle et al. reported that the risk of harboring a neoplastic lesion was significantly related to the duration of symptoms and to an age greater than 50 years. They concluded that pruritus ani was frequently a symptom attributable to other colonic and anorectal pathologies. Thus, the presence of prutitus ani of long duration, which is refractory to medical treatment, should alert the physician to the possibility of underlying colonic or anorectal neoplastic pathologies. Colonoscopy and other aggressive modalities involving the lower gastrointestinal tract are required [6]. If pruritus ani that does not respond to two to three weeks of conservative treatment, efforts should be made to find underlying diseases that may have been easily overlooked. This can be done by aggressively performing a biopsy on the area that is thought to be most appropriate for rendering a clinical diagnosis.

TREATMENT

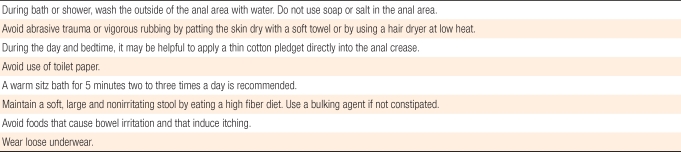

Treatment should be directed toward finding the underlying diseases. Most patients with secondary pruritus ani are improved after correction of the causative agent. For patients who are thought be suffering from idiopathic pruritus ani whose causative cannot be found, life style modification should be suggested (Table 2). Generally, the perianal skin should be maintained dry and clean and have weak acidity. Particularly, patients should be educated to clean the perianal area with water after defecation and to avoid severe rubbing. The anus should be dried with a hair dryer or carefully tapped with cottons swabs [9]. When a bidet is used, it is better to use warm water and relatively low water pressure to avoid irritation of the anus [10]. In regard to clothes, it is recommended to avoid underwear that cannot absorb sweat well and to wear loose cotton underwear [7, 9]. The use of topical steroids, anti-histamine agents, and sedatives may be of help. However, topical corticosteroids, especially if used for a long period, can cause atrophy, bacterial and fungal infections, allergic contact dermatitis, telangiectasia, purpura, and/or scar formation. Thus, their long-term use should be avoided. In addition, if constipation or defecation disorder is present, appropriate laxatives, as well as a high-fiber diet, may be of help.

Psyllium agents are of help in reducing the injury to the anal canal and in maintaining better hygiene of the perianal area. In addition, it is important to educate patients to avoid foods and drinks that exacerbate itching. As mentioned above, coffee, tea, cola, chocolate, and beer are considered to be causes of pruritus. In regard to coffee, Friend [7] have stated that coffee is associated with the induction of pruritus ani and that one hour after coffee consumption, the resting anal pressure is decreased [4, 11]. However, generally, the direct association of coffee with the induction of pruritus is not clear, and more accurate studies are required. Generally, many cases of pruritus ani can be treated readily by improving dietary habits, correcting bowel habits, and avoiding certain mechanical or chemical irritations.

For patients with persistent and severe pruritus that cannot be treated by general conservative methods, aggressive therapies have been attempted. For mild and moderate levels of pruritus ani in which skin discoloration in the perianal area is not severe, topical ointments, such as 1% hydrocortisone, can be applied [2, 3]. However, once the symptoms have improved, steroid use should be discontinued, if possible, and replaced with other barrier creams, such as zinc oxide, and the side effects caused by the indiscriminate use of steroid cream should be explained sufficiently to the patient by the primary doctor. For severe pruritus ani cases with severe skin discoloration of the perianal area, a strong steroid must be used for a short time, but topical treatments that are longer than several weeks are not generally recommended. Until now, a clear criterion for the duration of steroid use has not been established. Al-Ghnaniem et al. [12] reported that 1% hydrocortisone application for the treatment of pruritus ani resulted in a 68% improvement in symptoms compared to the placebo group. Although some investigators have stated that the local immune suppressor tacrolimus might be of help in preventing skin atrophy and anti-fungal effects, such data have not yet been reported [13].

Lysy et al. [14] reported that 0.006% topical capsaicin ointment was applied to 44 patients with incurable pruritus ani that was unresponsive to menthol treatments three times a day and that 31 patients showed an improvement of symptoms. Capsaicin is a natural alkaloid extracted from red chili peppers. Its pharmacological action is mainly depletion of substance P (neuropeptide) from sensory neurons. Generally, it has been used as a treatment for rheumatoid arthritis and neuralgia. Capsaicin causes a mild perianal burning sensation, but a concentration of 0.006% capsaicin rather than 1% or 0.5% is effective in alleviating pruritus ani without the significant burning sensation associated with more concentrated preparations. In the future, the topical application of capsaicin may be of help in treating pruritus ani, if the side effects of the long-term use of steroids or cases unresponsive to other topical therapies are considered.

Since the intradermal injection of methylene blue for the treatment of refractory pruritus ani was introduced by Rygick in 1968, diverse treatments have been attempted [15]. The mechanism of methylene blue's exerting therapeutic effects on pruritus ani has not been elucidated yet. Methylene blue may be directly toxic to the nerves supplying the perianal skin, thus suppressing the desire to scratch and disrupting the vicious itch-scratch-itch cycle [16]. According to studies that have been reported until now, good outcomes have been reported in 64% to 100% of the patients treated with methylene blue. Recently, some investigators stated that intradermal injection of 0.5-1.0% methylene blue mixed with lidocaine and a steroid had good outcomes for the treatment of intractable pruritus ani [17, 18]. Although there have been some reports on complications after tattooing, such as decreased perianal sensation, transient fecal incontinence and local inflammatory reactions in the injection area, it was well tolerated by the patients and resulted in no severe complications [19]. Therefore, it can be used to treat incurable pruritus ani [20].

CONCLUSION

Pruritus ani may manifest in response to various causes, particularly, dermal lesions, or diverse conditions of the anorectum. Hence, in outpatient clinics, attempts should aggressively be made to find its causes. Ultimately, it should be adjusted to the improvement of the symptoms and the consequent secondary skin discoloration. If the cause cannot be determined despite such efforts, the pruritus ani should be considered as idiopathic and management of the condition should focus on reducing the source of irritation, changing of lifestyle, and improving perianal hygiene [20]. In conclusion, for obtaining successful results from the treatment of pruritus ani, first of all, it is better to inform patients of the precise proceeding of the disease, the treatment strategies, and the possibility of recurrence, and the disease should be managed continuously.