- Search

Abstract

Colonic diverticulosis has continuously increased, noticeably left-sided diseases, in Korea. A colovesical fistula is an uncommon complication of diverticulitis, and its most common cause is diverticular disease. Confirmation of its presence generally depends on clinical findings, such as pneumaturia and fecaluria. The primary aim of a diagnostic workup is not to observe the fistular tract itself but to find the etiology of the disease so that an appropriate therapy can be initiated. We present here the case of a 79-year-old man complaining of pneumaturia and fecaluria. On abdomen and pelvis CT, the patient was diagnosed as having a colovesical fistula due to sigmoid diverticulitis. After division of the adhesion between the sigmoid colon and the bladder, the defect of the bladder wall was repaired by simple closure. The colonic defect was treated with a segmental resection, including the rectosigmoid junction. The patient is doing well at 6 months after the operation and shows no evidence of recurrence of the fistula.

Colonic diverticulosis refers to a small outpouching of the intestinal wall. It is classified histologically as true diverticula in which all layers of the bowel wall protrude or as false diverticula in which only the mucosal and submucosal layers protrude through the muscular layer. True diverticula are hereditary and develop more commonly in the right colon. In contrast, false diverticula are acquired diverticula due to degenerative changes of the bowel wall with aging and the lack of a high fiber diet, and they occur frequently in the left colon. The incidence of colonic diverticulosis is high in the West where diet fibers are consumed less. Nevertheless, it is not common in Korea, and it occurs more frequently in the right colon than the left colon.

Therefore, reports on the complication of a sigmoid colonic diverticulosis sigmoid colovesical fistula are very rare. When we searched the Korean medical database, we found only two papers [1, 2]. Nevertheless, in Korea, similarly, the elderly population is on the rise, and diets have become westernized; thus, the incidence of sigmoid diverticulitis and its complication of a sigmoid colovesical fistula is increasing. Recently, at our hospital, one case of sigmoid colovesical fistula caused by diverticulitis was experienced, and here we present a review of that case, along with a review of the literature.

A 79-year-old male patient was admitted to the Department of Urology at our hospital for the chief complaint of fecaluria and pneumaturia that had started two days earlier. His medical history showed that two years earlier, he visited a private clinic for the chief complaint of frequent urination and was diagnosed as having cystitis, which had improved after medication for 2 weeks; he was currently using antihypertensive drugs and aspirin for hypertension. During the past 5 years, he had been taking arthritic therapeutics for arthritis of the hip joint, and normal movements were not feasible; thus, he used a wheelchair. At the time of admission, on physical examination, fever or chill was not detected, and other than symptoms of bladder irritation symptoms, no other special findings were detected. Vital signs were normal. On physical examination, mild tenderness in the left lower quadrant was detected. Nevertheless, rebound tenderness or masses were not palpated.

Urine was opaque macroscopically, and in the urinalysis, the nitrite reaction was positive. On microscopic examination, leucocytes and bacteria were observed. In culture tests, E. coli were cultured. In complete blood tcount (CBC), the white blood cell count was 15,500/mm3, and the fraction of neutrophils was 69.9%. In abdominal computed tomography, gas within the bladder was detected, and a finding that the sigmoid colon and the dome of the bladder were severely adhering to each other was found. A thickening of the sigmoid colon and the bladder wall, as well as infiltration to adjacent adipose tissues, was shown. Nevertheless, no abscess or fistular tract was observed (Fig. 1). Based on the findings, a sigmoid colovesical fistula was suspected, and for collaborative surgery, the patient was transferred to the Department of Surgery. To assess the fistular tract, we performed cystography, but the fistula was not seen. A barium enema showed that along the fistula, dyes entered from the sigmoid colon to the bladder, and in the sigmoid colon, multiple diverticula were present (Fig. 2). On colonoscopic examination, hyperemic mucosal lesions, which were suspected to be diverticula, were detected in the area about 40 cm above the anal verge, and no special finding, which could be suspected of being a fistula or malignancy was observed.

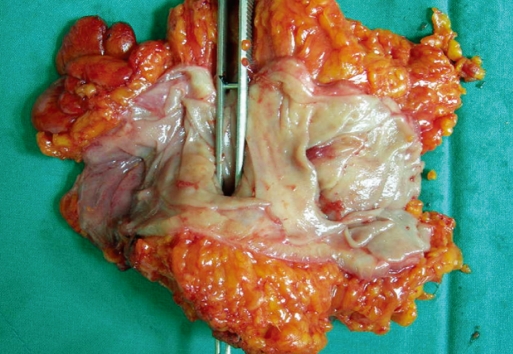

Based on the above examinations, a diagnosed of a sigmoid colovesical fistula caused by diverticulitis was formed, and open abdominal surgery was performed. In operative findings, the distal sigmoid colon was severely adhered to the dome of the bladder and overall to the base (Fig. 3); thus, the location of the fistula could not be assessed. Unavoidably, the bladder was incised, and a fistula located between the two ureteral openings was found. Because of the concern of possible ureteral injury, a double J catheter was inserted, and the surgery proceeded. First, the bladder and the sigmoid colon were separated, and after curettage, primary repair was performed on the fistular area of the bladder, and a segmental resection was performed on the colon, including the recto-sigmoid colon junction. In the resected sigmoid colon tissues, an abscess and a fistula caused by diverticulitis were observed (Fig. 4).

Diet was initiated from seven days after surgery, and no special problems developed. On day 14, to confirm the absence of bladder leakage, we performed cystography in order to remove the catheter. Nonetheless, after cystography, fever developed, and in the next early morning, together with a 39.3℃ high fever, symptoms of urinary sepsis, systolic blood pressure of 60 mm Hg, were observed. The patient responded to conservative treatments, such as rapid fluid injection and inotrophics, and the double J catheter was removed. On day 17, the patient was discharged after removal of the catheter, and during the follow-up observation 6 months after surgery, no complications or evidence of recurrence evidences was observed.

Colonic diverticulosis occurs with high frequency in the West where food containing low fiber content is consumed, but it is not common in Korea. However, recently, the incidence is on the rise even in Korea. This may be due to not only diverticulosis actually occurring more frequently due to the increased elderly population and the westernization of diet but also the detection rate increasing on account of the development of colonoscopy, abdominal computed tomography and other diagnostic methods, as well as active examination [3].

In the West, with aging, the incidence has increased. In the group younger than 40 years of age, the incidence of diverticulosis has been reported to be lower than 5%. On the other hand, in the group older than 80 years of age, it is 65% [4]. In Korea, the incidence in the general population has not been investigated. Nonetheless, among approximately 9,000 patients who received a colonoscopic examination, diverticulosis was reported to have been detected in 7.3% of the patients [5]. Approximately 10-20% of people with diverticula have been reported to progress to diverticulitis, and 10-20% of those have been reported to require hospitalization It has been reported that 20-50% of the hospitalized diverticulitis patients required surgery; thus, ultimately, surgery was required in less than 1% of all patients with diverticula [6, 7]. Surgery should typically be advised if an episode of complicated diverticulitis is treated nonoperatively and does not respond to nonoperavtive management [8].

The complication of colonic diverticulitis colovesical fistula is a relatively rare disease even in the West. The incidence of colovesical fistula in diverticular disease has been estimated to be approximately 2-4%, but has been reported to have a wide range between 2% and 23%. The most common cause of colovesical fistula is diverticulosis; however, it may be caused by malignant diseases, Crohn's disease, radiation, etc. The underlying mechanism is the direct extension of a ruptured diverticulum or secondary erosion of a diverticular abscess into the bladder [9, 10]. Pneumaturia or fecaluria are pathognomic for the diagnosis of colovesicular fistula, and it was detected in 71.4% and 51% cases, respectively, in which those complaints were found. On the other hand, a substantial number of patients present with frequent urination, dysuria, hematuria and other non-specific symptoms due to recurrent or persistent urinary tract infection; thus, the diagnosis of colovesical fistula may be delayed [9]. The aim of the diagnostic procedure for colovescular fistula is to seek appropriate therapeutic strategy by assessing the existence of the fistula and the underlying etiology. For patients who present with the non-specific symptoms of colovescular fistula, the presence of a fistula has to be assessed first. According to Kwon et al. [11], the average detection rate of fistulae is low: cystoscopy, 42.4%; cystography, 41.3%; barium enema, 35.3%; colonoscopy or sigmoid colonoscopy, 6.4%; and abdominal computed tomography, 30.8%. Nevertheless, recently, during an observation over a period of 48 hours immediately following the consumption of poppy seeds, the rate of the diagnosis of fistula was found to be higher than 90% [9, 12]. For cases in which the presence of a fistula is not clear, confirmation of the presence of fistula by using the inexpensive and simple poppy seed test, followed by tests to find the causatives, should be considered.

The rate of diagnosis of colovesicular fistula by using colonoscopy is as low as 6-8.5% [9, 11]. Nonetheless, it has advantages in that diverticulitis, cancer or inflammatory bowel diseases, which may be the cause, can be ruled out, and distal stenosis can be assessed. Concerning surgeries for colovesicular fistula caused by locally progressed cancer, a wide bowl resection and a resection of the bladder wall together with adjacent lymph nodes is required. For colovesicular fistula caused by benign diseases, it is sufficient to resect the inflamed bowel and perform primary repair of the bladder wall. Therefore, preoperative colonoscopy is a prerequisite [10]. By cystoscopy, only non-specific findings, such as bullous edema, which suggests a fistular tract, are shown, and the presence of a fistula is difficult to assess [9]. However, the relationship of the fistula to ureteral openings can be assessed. For cases with severe inflammation, in which injury to the ureter is, thus, a concern, a double J catheter may be inserted prior to surgery. Although rare, a colovesicuar fistula caused by advanced bladder cancer may be detected. If air within the bladder is detected by abdominal computed tomography, and the adhesion of the colon to the bladder, as well as wall thickening, are shown, a colovesicular fistula can be diagnosed. Nonetheless, the diagnosis rate averages 30.8% and varies from 11 to 100%, depending on investigator. The wide variation in the detection rates is likely due to small sample size in each reported study. However, it could be of great help in planning surgery because it could assess the presence of an abscess and the anatomical relationship with adjacent structures, as well as the cause of fistula [11].

According to the treatment guidelines of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, the recurrence of diverticulitis could be reduced if distally, the margin of resection were to be where the taenia coli splay out onto the upper rectum [8]. In our case, similarly, the resection was performed including that area. In cases of colovesicular fistula, the consensus on the treatment of a fistula on the side of the bladder has not been reached yet. According to Ferguson et al. [12], of 74 patients who developed a colovesicular fistula due to benign diseases, for 50 patients (67.6%) whose fistula was too small to detect, suture was not performed, and for the remaining patients, primary suture was performed; after placing the omentum between the bladder and the colon, followed by use of a Foley catheter for 1 week, a colocutaneous fistula and a vesicocutaneous fistula developed in only one case. Therefore, for cases in which the fistula cannot be seen distinctly, a partial resection of the bladder in the vicinity of the fistula and suture are not required. Conventionally, catheters are installed for 2 weeks and are removed after assessing the leakage by cystography. Nevertheless, in recent studies, installation of a catheter for longer than 1 week has been reported to increase complications, such as urinary tract infection, urine retention, bladder atony, etc., and a cystographic test is not required [13]. In our case, inflammation was severe, and the bladder was severely adhered to the colon over a wide area; thus, the fistula could not be found. The fistula was finally detected by performing a cystotomy. Inflammation was severe, a catheter was installed for 2 weeks and on day 14, cystography was performed. However, after cystography, sepsis developed temporarily. Considering retrospectively, if surgery had been performed after waiting for the inflammation to subside and the fistula to mature, the cystotomy could have been avoided, and the period of Foley catheterizatrion could have been shortened.

In summary, as in our case, for patients presenting with fecaluria, pneumaturia and other specific symptoms of a colovesicular fistula, Barium enema or cystography to confirm the presence of the fistula is not required; rather, finding the cause of the fistula and assessing the presence or absence of distal obstruction by performing abdominal computed tomography, colonoscopy, cystoscopy, etc. are important. During surgery, to prevent the recurrence of diverculitis, the colon, including the upper rectum, should be resected distally. For the area of the bladder fistula, if inflammation is not severe, as in our case, primary suture and bladder rest by an indwelling urinary catheter is thought to be sufficient.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the research grant of the Chungbuk National University in 2009.

References

1. Kim SW, Park JS, Nam SB, Kim JJ, Kim SC. Vesicosigmoidal fistula caused by diverticulitis. Korean J Urol 2005;46:1221–1223.

2. Kim HC, Yang DM, Lee SH, Joo SH. Ultrasonographic features of a colovesical fistula arising secondary to sigmoid colon diverticulitis: a case report. J Korean Soc Ultrasound Med 2008;27:153–156.

3. Choi CS, Cho EY, Kweon JH, Lim PS, No HJ, Kim KH, et al. The prevalence and clinical features of colonic diverticulosis diagnosed with colonscopy. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc 2007;35:146–151.

4. Heise CP. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of diverticular disease. J Gastrointest Surg 2008;12:1309–1311. PMID: 18278535.

5. Song JH, Huh JG, Kim YS, Lee JH, Jang WC, Ok KS, et al. Clinical characteristics of colonic diverticular disease diagnosed with colonoscopy. Intest Res 2008;6:110–115.

6. Roberts PL, Veidenheimer MC. Current management of diverticulitis. Adv Surg 1994;27:189–208. PMID: 8140972.

7. Somasekar K, Foster ME, Haray PN. The natural history diverticular disease: is there a role for elective colectomy. J R Coll Surg Edinb 2002;47:481–482. 484PMID: 12018691.

8. Rafferty J, Shellito P, Hyman NH, Buie WD. Standards Committee of American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Practice parameters for sigmoid diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum 2006;49:939–944. PMID: 16741596.

9. Melchior S, Cudovic D, Jones J, Thomas C, Gillitzer R, Thuroff J. Diagnosis and surgical management of colovesical fistulas due to sigmoid diverticulitis. J Urol 2009;182:978–982. PMID: 19616793.

10. Najjar SF, Jamal MK, Savas JF, Miller TA. The spectrum of colovesical fistula and diagnostic paradigm. Am J Surg 2004;188:617–621. PMID: 15546583.

11. Kwon EO, Armenakas NA, Scharf SC, Panagopoulos G, Fracchia JA. The poppy seed test for colovesical fistula: big bang, little bucks! J Urol 2008;179:1425–1427. PMID: 18289575.

12. Ferguson GG, Lee EW, Hunt SR, Ridley CH, Brandes SB. Management of the bladder during surgical treatment of enterovesical fistulas from benign bowel disease. J Am Coll Surg 2008;207:569–572. PMID: 18926461.

13. de Moya MA, Zacharias N, Osbourne A, Butt MU, Alam HB, King DR, et al. Colovesical fistula repair: is early Foley catheter removal safe? J Surg Res 2009;156:274–277. PMID: 19665732.

Fig. 1

Abdomen and pelvis computed tomography scan shows the presence of gas in the bladder (arrow) and wall thickening of the colon immediately adjacent to an area of locally thickened bladder: (A) sagittal view and (B) axial view.

Fig. 2

Barium enema examination shows the presence of barium within the bladder and fistular tract (arrow).

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

- Related articles in ACP

-

Enterovesical Fistula From Meckel Diverticulum2021 July;37(Suppl 1)

Toothpick Colon Injury Mimicking Colonic Diverticulitis2018 June;34(3)

Colouterine Fistula Caused by Diverticulitis of the Sigmoid Colon2012 December;28(6)

Colovesical Fistula: Should It Be Considered a Single Disease?2015 April;31(2)

The Wind of Change: Uncomplicated Diverticulitis2015 April;31(2)