- Search

|

|

See commentary "Complete Mesocolic Excision With Central Vascular Ligation for the Treatment of Patients With Colon Cancer" in Volume 34 on page 165.

Abstract

Purpose

Revolutions have occurred over the last 3 decades in the management of patients with colorectal cancer. Most advances were in rectal cancer surgery, especially after the introduction of the total mesorectal excision (TME) by Heald. However, no parallel advances regarding colon cancer surgeries have occurred. In 2009, Hohenberger introduced a new concept trying to translate the survival advantages of TME to patients with colon cancer. This relatively new concept of a complete mesocolic excision (CME) with central vascular ligation (CVL) in the management of patients with colon cancer represents an evolution in operative technique. We performed a comparative study between CME with CVL and conventional surgery for patients with colon cancer at Italian and Egyptian cancer centers, considering surgical quality and clinical outcome.

Methods

Seventy-nine Egyptian patients underwent conventional surgery (non-CME group) while 52 Italian patients underwent CME with sharp dissection between the embryological planes and CVL of the supplying vessels (CME group).

Results

Significantly better results were observed in terms of lymph node yield (CME group: 22.5 vs. non-CME group: 12; P < 0.0001) and lymph node ratio (CME group: 0.03 vs. non-CME group: 0.22; P < 0.0001). Regarding surgical morbidity, no significant difference was noted (CME group: 2 vs. non-CME group: 5; P < 0.702).

Conclusion

CME appears to be a safe procedure when performed by experienced hands through proper embryological planes. It also provides a superior specimen, with a higher lymph node yield, which consequently affects the lymph node ratio. Eventually, CME with CVL should be increasingly adopted and studied more deeply.

Colon cancer is a major public health problem worldwide, being the fourth most common epithelial tumor and the second highest cause of cancer death in the United States [1]. In Italy, it is the second most common tumor and the leading cause of death [2]. In Egypt, a non-EU Mediterranean country, the incidence of colon cancer is relatively low, but its mortality rate is high [3]. Revolutions have occurred over the last three decades in the management of patients with colorectal cancer. The best example of this is the anatomic description of the mesorectum and the introduction of the total mesorectal excision (TME) by Heald et al. [4] in the early 1980s. In analogy to the TME as a rectal cancer surgical procedure, a complete mesocolic excision (CME) was recently introduced by Hohenberger et al. [5] in 2009 as a curative treatment for patients with colon cancer. Similar to the TME, the CME aims at complete en bloc clearance of the tumor’s lymphatic drainage enveloped in the intact fascia of embryologic origin.

The concept of a CME depends on 2 components, sharp dissection of the anatomical layers and the dissection of the visceral plane from the parietal one. The resulting specimen shows the tumor and its lymphatic drainage with no tears in the fascial layers on each side of the mesocolon. In addition, a central division of the feeding arteries at their origins is performed at the level of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) for tumors of the right colon and at the level of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) or the aorta for tumors of the left colon. This allows for removal of the maximum number of lymph nodes possible [6]. Two series were used to analyze CME with central vascular ligation (CVL); one was done at University Hospital of Erlangen, Erlangen, Germany (CME specimens), and the other at St. James’s University Hospital, University of Leeds, Leeds, United Kingdom (non-CME specimens). The results showed that a CME led to an almost doubling of both the number of lymph nodes retrieved and the area of the mesentery resected [7].

Another prospective study concentrating on right-side tumors, as a left hemicolectomy is better codified and more widely used, was done at the University of Campania, Naples, Italy. It showed a significant increase in the number of lymph nodes harvested and in the number of mesocolic tumor deposits, which allowed the upstaging of 6 patients to subsequent adjuvant chemotherapy [8]. In Denmark, a comparative study between a CME group, Hiller√∏d Hospital, and a non-CME control group from another three hospitals was done regarding short-term outcomes. It showed that CME might be associated with a higher morbidity, but that association was not statistically significant [9].

On the other hand, many oncologists argue against the true benefits gained by using a more challenging technique with potentially major added morbidity [10]: particularly, the uselessness of extended resections, the absence of randomized controlled trials and comparative studies, and the fact that most experience is from a single center [11]. Therefore, cohort studies comparing CME with conventional surgery might be the only way to explain any differences between the 2 techniques.

From January 2016 to December 2016, 52 patients with colon cancer underwent a potentially curative CME with CVL colectomy (CME group) at the Division of Surgical Oncology, Department of Abdominal Oncology, Istituto Nazionale Tumori Fondazione G. Pascale-IRCCS, Naples, Italy, and their cases were prospectively analyzed. The results for this group were compared with the results for another group, including 79 patients who underwent a potentially curative classic or conventional colectomy (non-CME group) from June 2012 to November 2015 at the Surgical Oncology Unit, Oncology Center, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt. Approvals were obtained from the local ethical committees at both the University of Mansoura and the National Cancer Institute at Naples in accordance with Egyptian and Italian bioethics laws in concordance with the Helsinki Declaration Principals. The study was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov with the identifier NCT02526836.

This comparison aimed to evaluate the possible oncological advantages of a CME with regards to qualitative markers (number of harvested lymph nodes, lymph node ratio [LNR]), as well as the morbidity and the mortality rates. Patients who met the following criteria were selected: age between 20 and 80 years; adequate organ function, including liver and cardiovascular functions; pathologically proven adenocarcinoma or adenosquamous carcinoma on endoscopic biopsy; tumor located in the caecum, ascending, transverse, descending, sigmoid or rectosigmoid colon on preoperative endoscopy and radiographic imaging; and provision of written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: contraindications to major surgery and American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification grade of IV, extreme systemic disorders which have already become an eminent threat to life; history of familial adenomatous polyposis, ulcerative colitis, or Crohn disease; infectious disease that requires treatment; pregnancy; history of psychiatric disease; use of systemic steroids; and history of unstable angina pectoris or myocardial infarction within 6 months. Tumor histopathological classification was applied according to the World Health Organization’s rules [12]. Staging was according to the 7th edition of the TNM classification [13]. Patients with stage III–IV disease received systemic chemotherapy postoperatively.

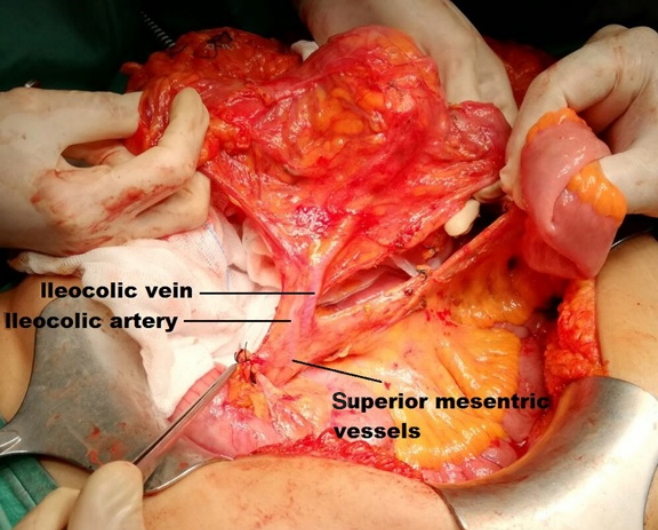

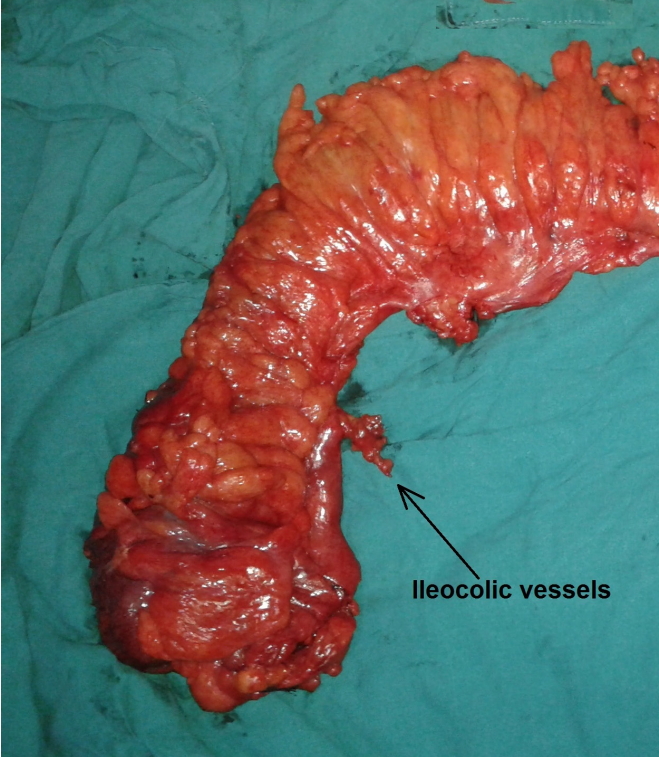

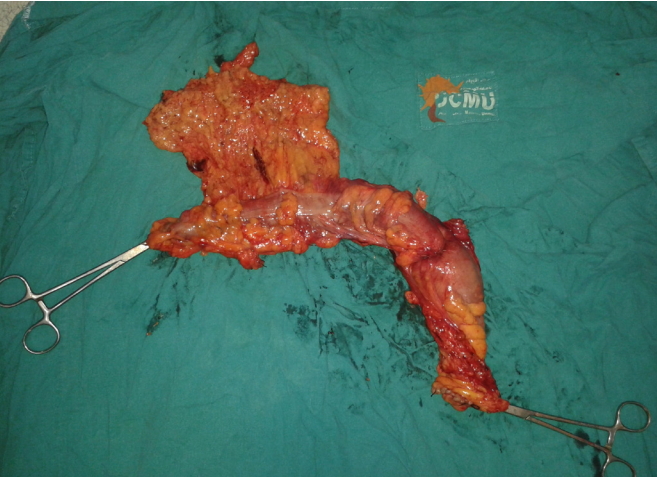

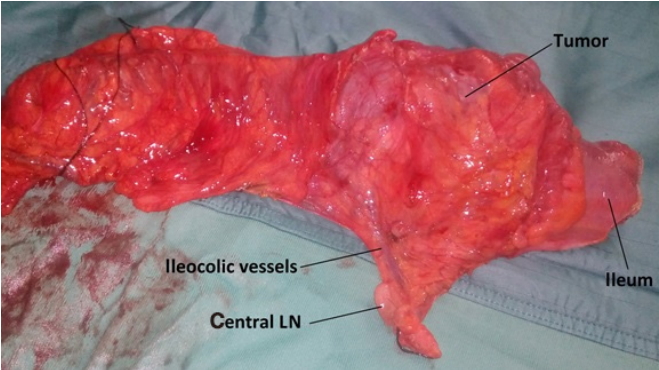

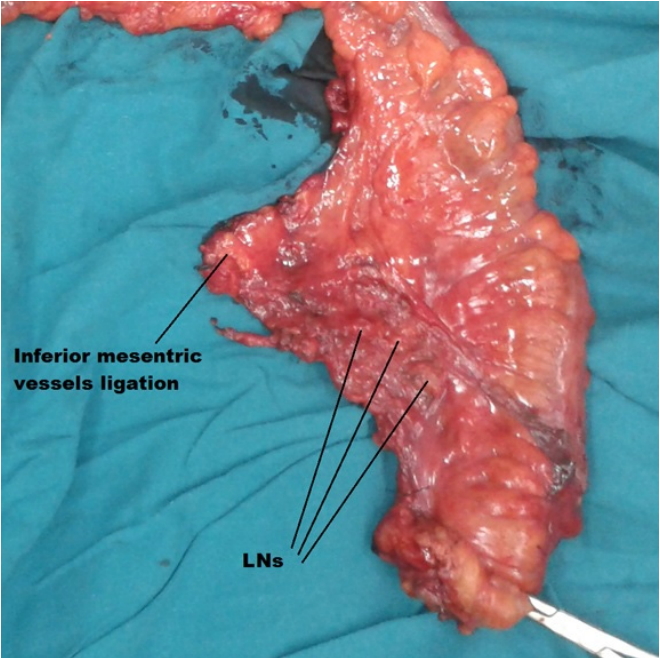

All colectomies were performed through an open midline laparotomy by the same experienced surgical team in each unit. In the Egyptian experience (non-CME group), the terminal ileum and colon, according to tumor location, were initially severed, and the mesocolon was divided in a V-shape manner at a location that was anatomically convenient. Therefore, ileo-colic vessels, right colic vessels (if present) in the case of right-sided tumors, the trunk of the middle colic vessels in the case of a transverse, extended right or left colectomy, or left colic or inferior mesenteric vessels in the case of left-sided and sigmoid tumors were severed in the mesocolon without identification of their origins. In the Italian experience (CME group), the surgical technique was obviously different [5, 14]. It had 2 components: In the first, a sharp meticulous dissection of the anatomical layers in which the visceral plane was dissected from the parietal one along the Toldt fascia with complete mobilization of the entire mesocolon up to the mesenteric root was performed. The resulting specimen shows the tumor and its lymphatic drainage with no tears in the fascial layers on each side of the mesocolon. In the second component, a central division of the feeding arteries at their origins is performed. For right-side tumors, the division is done at the level of the SMA (Figs. 1, 2) while for left-side tumors, the division is done at the level of the IMA or the aorta (Fig. 3). This allows for removal of the maximum number of lymph nodes possible [6, 15]. Kocher maneuver, as described by S√∏ndenaa et al. [16], though potentially beneficial, was not used. Finally, in both groups, a hand-sewn, side-to-side ileocolic or colocolic anastomosis or a circular stapler anastomosis in the case of sigmoid or rectosigmoid tumors was done.

All patients were discharged from the hospital and received adjuvant chemotherapy in the form of 5-fluorouracil plus oxaliplatin, if needed (pT4, node positive, or metastatic cancers) [17]. The patients’ TNM classifications are presented in Table 1. Additionally, analyses of the lymph node yield, the number of positive lymph nodes, and the LNR, which is the number of positive lymph nodes divided by the total number of removed nodes [18], were done. In addition, tumor location, type of surgical procedure, morbidity, mortality, clinical outcome, and postoperative outcome were recorded.

The extracted data were recorded using Excel spreadsheets under Microsoft Windows (Bristol, UK), and all the statistical analyses were performed using Stata 12 (StataCorp LP., College Station, TX, USA). Categorical variables were reported as numbers and percentages. Continuous variables were described as means ± standard deviations or median and interquartile range according to the distribution. The chi-square test or Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables, and the Student t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test was used when appropriate to detect differences between continuous variables. P-values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Between June 2010 and November 2015, 79 patients (38 females and 41 males) were admitted to the Surgical Oncology Unit of Mansoura University’s Oncology Center for surgery. As to the locations of the tumors, 20 patients were diagnosed with cecal cancer; in 11 patients, the tumor was located in the ascending colon, in 8, it was located in the hepatic flexure, in 7, it was located in the transverse colon, in 4, it was located in the splenic flexure, in 14, it was located in the descending colon, and in 15, it was located in the sigmoid colon (Table 1). All patients underwent a R0 resection, with 2 patients underwent a nonanatomical liver resection for peripheral hepatic metastasis. The median lymph node yield was 12 (range, 9–16), a significant decrease in comparison to the CME group (median, 22.5; range, 15–30; P < 0.0001), which was reflected in the LNR which had a mean = 0.22, significantly higher than the CME group (0.03; P < 0.0001) (Table 2). After histopathological examination, a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma was found in 50 patients and a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma was found in 2 patients.

All patients had elective surgeries: 21 right hemicolectomies, 9 extended right hemicolectomies, 6 left hemicolectomies and 16 sigmoidectomies. No intraoperative adverse events occurred. The average duration of surgery was 135 minutes, and the average intraoperative blood loss was 105 mL. Postoperative complications occurred in two patients. One of them had an anastomotic leakage that was managed conservatively; the other had an incisional hernia and underwent surgery 6 months later. No in-hospital mortality occurred.

Between June 2010 and November 2015, 79 patients (38 females and 41 males) were admitted to the Surgical Oncology Unit of Mansoura University’s Oncology Center for surgery. As to the locations of the tumors, 20 patients were diagnosed with cecal cancer; in 11 patients, the tumor was located in the ascending colon, in 8, it was located in the hepatic flexure, in 7, it was located in the transverse colon, in 4, it was located in the splenic flexure, in 14, it was located in the descending colon, and in 15, it was located in the sigmoid colon (Table 1). All patients underwent a R0 resection, with 2 patients underwent a nonanatomical liver resection for peripheral hepatic metastasis. The median lymph node yield was 12 (range, 9–16), a significant decrease in comparison to the CME group (median, 22.5; range, 15–30; P < 0.0001), which was reflected in the LNR which had a mean = 0.22, significantly higher than the CME group (0.03; P < 0.0001) (Table 2).

All patients underwent elective surgeries: 31 right hemicolectomies, 15 extended right hemicolectomies, 21 left hemicolectomies, 4 extended left hemicolectomies and 8 sigmoidectomies (Figs. 4, 5). On histopathological examination, a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma was found in 3 patients, a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma in 66, and a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma in 10. No major intraoperative complications were encountered. The average duration of surgery was higher in comparison with the CME group (180 minutes vs. 135 minutes, P < 0.0001). Also, the intraoperative blood loss was higher (200 mL vs. 105 mL, P < 0.0001). The number of postoperative complications (n = 5) was higher compared to the CME group, but the difference did not reach a statistical significance (P = 0.702). Two patients experienced anastomotic leakage; one of them needed reoperation and the other was managed conservatively. Two patients with postoperative collection were managed conservatively, and one patient who developed an incisional hernia not to undergo surgery to correct it. No in-hospital mortality occurred (Table 2).

The outcomes of patients who undergo a curative resection for rectal cancer have improved in many countries after the adoption of the TME, which is the standard procedure for the treatment of patients with rectal cancer [4, 19]. However, internationally, no standard surgical procedure for the treatment of patients with colon exists. The CME, a relatively new concept in the management of patients with colon cancer, represents an evolution in surgical technique. It attempts to generalize the progress of rectal cancer managed by using the TME, as well as its survival advantages, to patients with colon cancer. While many guidelines rule the colon-cancer diagnosis [20], far fewer attempts have been made to legislate specifics for the operative technique. Several surrogate markers for the quality of cancer management have been adopted, and the number of resected lymph nodes has been endorsed as the standard of operative quality for certain stages of the disease [21, 22].

Although the CME is still relatively new, early results are promising. The CME has been confirmed to produce superior specimen quality in comparison to conventional colon surgery [7]. The CME also maximizes the number of lymph nodes harvested, which represents an important surrogate quality marker for optimized oncological results [23, 24]. Likewise, adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with positive lymph nodes plays a significant role in improving outcome [25]. However, adjuvant chemotherapy cannot substitute for deficiencies in surgical quality. Therefore, combining the advantages of the CME with the significant benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy represents a multidisciplinary approach to improving outcomes in patients with colon cancer.

An important study published in 2014 by Lancet Oncology, showed a significant increase in the disease-free survival (DFS) in the CME group in comparison to the non-CME one (85.8% vs. 75.9%), which reveals that implementation of CME surgery might improve outcomes for patients with colon cancer [26]. In our study, although the data showed that a combination of CME and CVL in comparison to the conventional technique did not increase or decrease intra- and postoperative complications, the data did show that the number of lymph node harvested was significantly increased, consequently reducing the LNR, which has a strong correlation to DFS [27]. As previously mentioned, following the principles of a combined CME and CVL will affect the number of lymph nodes harvested, cover a wide drainage area, including the CVL area, and include central or apical lymph nodes that are missed in a classic dissection, leading to possible understaging from stage III to stage II; such missed micrometastases could lead to future local recurrence.

The authors of many studies oppose using the CME technique because of possible morbidities resulting from the extended lymphadenectomy. In our study, no significant difference between the morbidity rates of the 2 groups was found. This may be attributed to the surgeons’ experience in following the embryological planes and careful dissection of the central supplying blood vessels. The results of this study should encourage surgeons to consider the CME plus CVL technique for the treatment of patients with colon cancer because it produces superior specimens following the embryological planes, increases the lymph node yield with a lower LNR, and has acceptable morbidity rates.

A limitation to this study is the inclusion of patients from two different centers. However, having more centers involved was advocated by those who are still not convinced of the advantages of using the CME technique [9]. Moreover, this study does not the reach the evidence level of a randomized clinical trial. Due to the difficulties in designing and carrying out such trials, cohort or population studies may provide a alternative reasonable way to compare the TME with the CME plus CVL technique.

In summary, regarding the number of harvested lymph nodes, the LNR, and intact planes, the CME plus CVL technique provides superior specimens over the conventional technique. Because the CME plus CVL technique is technically challenging, a thorough understanding of the applicable anatomy is crucial in order to dissect through the proper plane. Eventually, the CME with CVL technique will be increasingly adopted for the treatment of patients with colon cancer, and until that time, the technique should be studied more thoroughly. Moreover, more comparative studies are needed for deeper evaluation of this technique and its outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors express their sincere appreciation to Dr. Hossam Elfeki for his valuable help with the statistics.

Fig.¬Ý2.

Right hemicolectomy specimen (CME + CVL). CME, complete mesocolic excision; CVL, central vascular ligation; LN, lymph node.

Fig.¬Ý3.

Left hemicolectomy specimen (CME + CVL). CME, complete mesocolic excision; CVL, central vascular ligation; LN, lymph node.

Table¬Ý1.

Clinico-pathological characteristics

Table¬Ý2.

Analysis of end-points

REFERENCES

2. AIRTUM Working Group, Busco S, Buzzoni C, Mallone S, Trama A, Castaing M, et al. Italian cancer figures--Report 2015: The burden of rare cancers in Italy. Epidemiol Prev 2016;40(1 Suppl 2):1–120.

3. Ibrahim AS, Khaled HM, Mikhail NN, Baraka H, Kamel H. Cancer incidence in egypt: results of the national population-based cancer registry program. J Cancer Epidemiol 2014;2014:437971.

4. Heald RJ, Husband EM, Ryall RD. The mesorectum in rectal cancer surgery--the clue to pelvic recurrence? Br J Surg 1982;69:613–6.

5. Hohenberger W, Weber K, Matzel K, Papadopoulos T, Merkel S. Standardized surgery for colonic cancer: complete mesocolic excision and central ligation--technical notes and outcome. Colorectal Dis 2009;11:354–64.

7. West NP, Hohenberger W, Weber K, Perrakis A, Finan PJ, Quirke P. Complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation produces an oncologically superior specimen compared with standard surgery for carcinoma of the colon. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:272–8.

8. Galizia G, Lieto E, De Vita F, Ferraraccio F, Zamboli A, Mabilia A, et al. Is complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation safe and effective in the surgical treatment of right-sided colon cancers? A prospective study. Int J Colorectal Dis 2014;29:89–97.

9. Bertelsen CA, Neuenschwander AU, Jansen JE, Kirkegaard-Klitbo A, Tenma JR, Wilhelmsen M, et al. Short-term outcomes after complete mesocolic excision compared with ‘conventional’ colonic cancer surgery. Br J Surg 2016;103:581–9.

10. Chow CF, Kim SH. Laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision: West meets East. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:14301–7.

11. Willaert W, Ceelen W. Extent of surgery in cancer of the colon: is more better? World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:132–8.

12. Toyota S, Ohta H, Anazawa S. Rationale for extent of lymph node dissection for right colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 1995;38:705–11.

13. Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:1471–4.

14. West NP, Kobayashi H, Takahashi K, Perrakis A, Weber K, Hohenberger W, et al. Understanding optimal colonic cancer surgery: comparison of Japanese D3 resection and European complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1763–9.

15. Manceau G, Panis Y. What is really meant by “complete mesocolic excision?”. J Visc Surg 2016;153:401–2.

16. Søndenaa K, Quirke P, Hohenberger W, Sugihara K, Kobayashi H, Kessler H, et al. The rationale behind complete mesocolic excision (CME) and a central vascular ligation for colon cancer in open and laparoscopic surgery: proceedings of a consensus conference. Int J Colorectal Dis 2014;29:419–28.

17. Alberts SR, Sargent DJ, Nair S, Mahoney MR, Mooney M, Thibodeau SN, et al. Effect of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin with or without cetuximab on survival among patients with resected stage III colon cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA 2012;307:1383–93.

18. Wang J, Hassett JM, Dayton MT, Kulaylat MN. Lymph node ratio: role in the staging of node-positive colon cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:1600–8.

19. Martling A, Holm T, Rutqvist LE, Johansson H, Moran BJ, Heald RJ, et al. Impact of a surgical training programme on rectal cancer outcomes in Stockholm. Br J Surg 2005;92:225–9.

20. Rim SH, Seeff L, Ahmed F, King JB, Coughlin SS. Colorectal cancer incidence in the United States, 1999-2004 : an updated analysis of data from the National Program of Cancer Registries and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer 2009;115:1967–76.

21. Baxter NN. Is lymph node count an ideal quality indicator for cancer care? J Surg Oncol 2009;99:265–8.

22. Wright FC, Law CH, Berry S, Smith AJ. Clinically important aspects of lymph node assessment in colon cancer. J Surg Oncol 2009;99:248–55.

23. Chen SL, Bilchik AJ. More extensive nodal dissection improves survival for stages I to III of colon cancer: a population-based study. Ann Surg 2006;244:602–10.

24. Link KH, Kornmann M, Staib L, Redenbacher M, Kron M, Beger HG, et al. Increase of survival benefit in advanced resectable colon cancer by extent of adjuvant treatment: results of a randomized trial comparing modulation of 5-FU + levamisole with folinic acid or with interferon-alpha. Ann Surg 2005;242:178–87.

25. André T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, Navarro M, Tabernero J, Hickish T, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2343–51.