- Search

| Ann Coloproctol > Epub ahead of print |

|

Abstract

Purpose

Complex anal fistulas can recur after clinical healing, even after a long interval which leads to significant anxiety. Also, ascertaining the efficacy of any new treatment procedure becomes difficult and takes several years. We prospectively analyzed the validity of Garg scoring system (GSS) to predict long-term fistula healing.

Methods

In patients operated for cryptoglandular anal fistulas, preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and postoperative MRI was done at 3 months to assess fistula healing. Scores as per the GSS were calculated for each patient at 3 months postoperatively and correlated with long-term healing to check the accuracy of the scoring system.

Results

Fifty-seven patients were enrolled, but 50 were finally included (7 were excluded). These 50 patients (age, 41.2±12.4 years; 46 males) were followed up for 12 to 20 months (median, 17 months). Forty-seven patients (94.0%) had complex fistulas, 28 (56.0%) had recurrent fistulas, 48 (96.0%) had multiple tracts, 20 (40.0%) had horseshoe tracts, 15 (30.0%) had associated abscesses, 5 (10.0%) were suprasphincteric, and 8 (16.0%) were supralevator fistulas. The GSS could accurately predict long-term healing (specificity and high positive predictive value, 31 of 31 [100%]) but was not very accurate in predicting non-healing (negative predictive value, 15 of 19 [78.9%]). The sensitivity in predicting healing was 31 of 35 (88.6%).

Anal fistulas, especially the complex variants, are challenging to treat [1]. One of the main issues is the high recurrence rate associated with complex fistulas [2, 3]. Apart from the high rate, the other problem with recurrence is a high level of unpredictability associated with recurrence [4]. A fistula that may appear clinically well healed (cessation of all pus discharge and absence of any swelling or pain in the perianal region) can still recur months and even years after surgery [4]. This causes a lot of anxiety and frustration in patients’ minds as even a clinical cure provides little reassurance, and the fear of recurrence looms large for several years [5]. Another problem with unpredictability is that it becomes quite difficult to ascertain the efficacy of any procedure utilized for anal fistulas [4]. It is not uncommon that a new procedure innovated for anal fistulas seems effective initially, but with the passage of time (when long-term follow-up becomes available), the success rate drops dramatically [6-8]. Therefore, a scoring system that could accurately predict long-term fistula healing would greatly help surgeons and patients.

Garg et al. [5] proposed a new scoring system (Garg scoring system [GSS]) which was shown to be effective in predicting long-term healing in cryptoglandular anal fistulas with a positive predictive value (PPV) of 98.2%. This was the first scoring system described for cryptoglandular anal fistulas. However, that was a retrospective study [5]. The validity of the new scoring system (GSS) is evaluated prospectively in this study.

The study was conducted at a referral center in India, which deals exclusively with anal fistulas. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent was obtained from all the patients. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Indus International Hospital (No. EC/IIH-IEC/SP6).

In a prospective study, all consecutive patients operated for anal fistula over 8 months from July 2020 to February 2021 and in whom preoperative and postoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess fistula healing was done at 3 months postoperatively were included. Only patients with cryptoglandular fistulas were included, and patients with Crohn disease were excluded. Long-term clinical healing was defined as complete healing of all the fistula tracts (complete cessation of pus discharge from the anus as well as all the external openings) with a minimum follow-up of at least 1 year. If there was pus discharge from even a single tract, then the fistula was considered non-healed. All the MRI scans were interpreted independently by 2 experts who had extensive experience in analyzing fistula MRI scans, including the MRI done in the postoperative period [9]. The MRI of every patient was then discussed to reach a consensus. Cases in which no consensus could be reached were excluded from the analysis.

The fistulas were classified under the Parks classification and St James’s University Hospital (SJUH) classification. The fistulas in early grades (Parks I or SJUH I–II) were classified as simple fistulas and higher grades (Parks II or SJUH III–V) were categorized as complex fistulas. Fistulotomy was performed for simple fistulas, and transanal opening of intersphincteric space (TROPIS) was performed for complex fistulas [10-12]. The TROPIS procedure is a modification of ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) in which the fistula tract in the intersphincteric space is not ligated but laid open into the anal canal through the transanal route. The intention is that the fistula tract in the intersphincteric space heals by secondary intention because, in the presence of sepsis, healing by secondary intention is better than by primary intention [10].

Six parameters were assessed as per the GSS postoperatively 3 months after surgery. Out of 6, 4 parameters were MRI-based (to be assessed on postoperative MRI), and 2 were clinical (Table 1). Each parameter was allotted a score of 0 or 1. Then, as per the importance of each parameter in the healing process, a definite weight was assigned to each parameter which was then utilized to get a minimum and a maximum possible score for each parameter.

The MRI-based parameters were healing of the internal (primary) opening (healed, 0 and not healed, 4), healing of the fistula tract in the intersphincteric space (healed, 0 and not healed, 4), healing of the external tracts in the ischiorectal fossa (healed, 0 and not healed, 1), and development of a new abscess in intersphincteric space in the postoperative period (on MRI) (absent, 0 and present, 4). The 2 clinical parameters were passage of flatus from any of the external openings (clinical) (absent, 0 and present, 4) and persistent discharge (pus or serous) from any external opening or anus (clinical) (no discharge, 0; serous discharge, 1; purulent but < 50% of preoperative level, 2; and purulent but > 50% of preoperative level, 3) (Table 1). Thus, the maximum possible score was 20, and the minimum possible score was 0. The cutoff score was 8. A GSS score of < 8 indicated that the fistula had healed at 3 months and would remain healed on a long-term basis. On the other hand, a weighted score of ≥ 8 implied that the fistula had not healed at 3 months and would not heal after that.

The StatsDirect software for statistics was used (StatsDirect Ltd., Merseyside, UK). The categorical variables were compared using Fisher exact test or chi-square analysis. When the data were normally distributed, the continuous variables were analyzed by t-test when there were 2-sampled or analysis of variance test when there were more than 2 samples. If the data were not distributed normally, Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied for paired samples, and the Mann-Whitney U-test was performed for unpaired samples. The significant cutoff point was set at P<0.05.

A total of 57 patients were included in the study. Out of these, 50 patients were included in the final analysis, and 7 patients were excluded (4 patients were lost to follow up and postoperative MRI could not be done at 3 months postoperatively in 3 patients). The patients (age, 41.2±12.4 years; 46 males) were operated on with a follow-up of 12–20 months (median, 17 months). In the cohort, most of the fistulas were complex fistulas (Park’s grade II–IV or SJUH grade III–V); 47 of 50 (94.0%). In the study, 28 (56.0%) had recurrent fistulas, 48 (96.0%) had multiple tracts, 20 (40.0%) had horseshoe tracts, 15 (30.0%) had associated abscesses, 5 (10.0%) were suprasphincteric, and 8 (16.0%) were supralevator fistulas (Table 2).

The new scoring system could accurately predict long-term healing (specificity and high PPV, 31 of 31 [100%]) but was not very accurate in predicting non-healing (negative predictive value [NPV], 15 of 19 [78.9%]). The sensitivity in predicting healing was 88.6% (31 of 35) (Table 3).

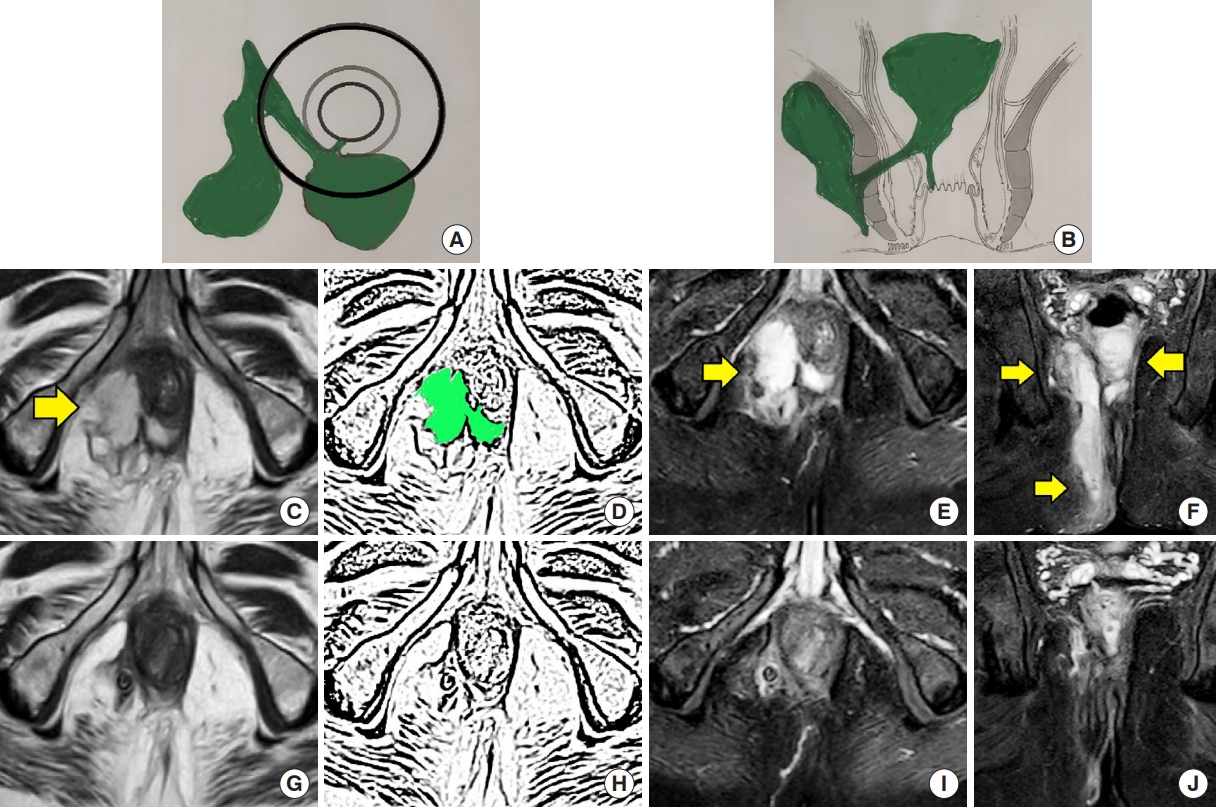

In the subset in whom GSS predicted healing and the fistula remained healed on long-term (true positive, n=31) (Fig. 1), the mean weighted scores were 2.2±2.5 (median, 2) (Table 4). While, in the subset in whom GSS predicted non-healing and the fistula remained non-healed on long-term (true negative, n=15) (Fig. 2), the mean weighted scores were 10.9±0.5 (median,10) whereas the patients in whom the scoring system predicted non-healing but the fistula healed on long-term (false negative, n=4) (Fig. 3), the mean weighted scores were 9.6±0.9 (median, 10) (Table 4, Fig. 3). The details of 4 patients with false-negative result have been tabulated in Table 5.

The study corroborates and validates the efficacy of the GSS. The study’s main strength is that it evaluated the scoring system prospectively. It demonstrated that GSS had a high (100%) PPV (PPV), though the NPV was not that high (78.9%). This indicates that once the fistula is healed as per GSS (score < 8) done 3 months after surgery, then the chances of fistula recurrence are quite low. This is creditable because it would provide significant reassurance to the patients and the operating surgeon. Also, as discussed above, it happens not uncommonly that a new procedure innovated for anal fistulas looks effective initially, but as the long-term follow-up becomes available, the success rate drops down significantly. This leads to significant wastage of time and precious resources and adds to patient morbidity. The availability of an effective scoring system would facilitate the rapid evaluation of newer surgical procedures.

The reasons for the lower NPV are not difficult to understand. The complexity of fistulas (number of tracts, width of tracts, magnitude of infection, etc.) can vary greatly. So, it is probable that all fistulas would not heal 3 months after surgery. Therefore, in 4 patients, the GSS score was ≥ 8 (predicting that the fistula would not heal) but the fistula still healed. Therefore, in more complex fistulas, it is prudent to get a postoperative MRI and evaluate GSS at a later interval (4–6 months after surgery) rather than at 3 months. This would reduce the chances of false negatives. The point of time to calculate GSS was chosen at 3 months postoperatively because most fistulas heal clinically and radiologically by 3 months. Before 3 months, it is difficult to differentiate between postoperative tissue inflammation, healing granulation tissue, and active fistula tract [9, 13]. Expectedly, delaying the point of time (4–6 months) would decrease the NPV, but it was practically difficult to make all patients wait for that long.

The main utility of GSS in clinical practice would be in high complex cryptoglandular fistulas, which have already recurred a few times. Preoperative MRI is usually done anyway in such cases, and along with that, if a postoperative MRI is also done, then GSS evaluation and long-term healing can be predicted.

Due to logistic reasons, it was easier to conduct a validation study of GSS at our center. Apart from the high incidence of fistulas in India, the main reason was the availability of very economical MRI scan facilities. Unlike North America and Europe, where MRI scan is costly, in India, the MRI scan costs the patient only 60–80 US dollars. Therefore, most patients with complex fistulas do not mind getting repeat postoperative MRI scans. Since the initial study was retrospective, we were keen to check the validity of GSS in a prospective study.

GSS was the first scoring system published to predict long-term healing in cryptoglandular anal fistulas. However, a few scoring systems had earlier been proposed for Crohn perianal fistulas like Van Assche scores, MAGNIFI-CD scores, and modified Van Assche scores [14-16]. The first scoring system was published by Van Assche et al. [14] to check the effects of infliximab on perianal Crohn disease in 18 patients. This scoring system was modified by Samaan et al. [15] in 2017 who analyzed it in a cohort of 50 patients with Crohn disease. In 2019, Hindryckx et al. [16] proposed MAGNIFI-CD scores to assess the response of Crohn fistulas to stem cell treatment. All these scoring systems evaluated the response of Crohn anal fistulas to medical treatment only, and none of these assessed healing after surgery [14-16]. Also, these scoring systems did not correlate accurately with postoperative healing [16, 17]. There were a few possible reasons for this. These scoring systems did not utilize any clinical parameters and were based on MRI-evaluated parameters only [14-16]. This was perhaps a mistake as anal fistula healing is a clinical phenomenon, and for the prediction of a scoring system to be accurate, clinical assessment parameters should be included in the scoring system. This could possibly explain that GSS was more accurate because, unlike previous scoring systems, GSS includes both clinical and MRI parameters. Another reason could be that the earlier scoring systems described for Crohn disease included preoperative features of fistula complexity like an associated abscess, multiple tracts, supralevator extension, etc., as their scoring parameters [14-16]. No doubt, these features that make a fistula complex preoperatively may decrease the chances of postoperative healing, but these parameters are not necessarily the markers of fistula non-healing in the postoperative period [18-20]. They are therefore confounding parameters and may not accurately correlate with post-treatment healing. Hence, these preoperative features were not included in GSS. The higher accuracy of GSS as compared to previous scoring systems further corroborates this point.

This study had some limitations. The sample size was small. Including Crohn fistulas would have added more value to the study. Though GSS was described for cryptoglandular anal fistulas, it would be interesting to evaluate its accuracy for Crohn fistulas.

To conclude, the newly described GSS accurately predicts fistula healing with a high PPV indicating that a fistula deemed healed by GSS would have an extremely low chance of recurrence. However, the NPV is not that high, indicating that a fistula predicted not to heal still has more than a 20% chance of healing. Further studies are needed to corroborate the findings of this study.

Fig. 1.

A 52-year-old male patient was operated for right-sided high transsphincteric abscess with supralevator extension. The fistula healed completely on clinical examination at postoperative 3 months with no symptoms or signs. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) done at that time showed healed tracts with weighted score of 0 (as per Garg scoring system). The patient is asymptomatic 22 months after surgery. (A) Axial section (schematic diagram). (B) Coronal section (schematic diagram). (C) Preoperative axial T2-weighted MRI. (D) Sketch of Fig. 1C highlighting transsphincteric abscess in green color. (E) Preoperative axial-STIR MRI. (F) Preoperative coronal STIR MRI. (G) Postoperative 3-month axial T2-weighted MRI. (H) Sketch of Fig. 1G. (I) Postoperative 3-month axial STIR MRI. (J) Postoperative 3-month coronal STIR MRI. Yellow arrows indicate fistula location. STIR, short tau inversion recovery.

Fig. 2.

A 45-year-old male patient was operated for right-sided high transsphincteric horseshoe fistula. The fistula healed completely on clinical examination at postoperative 3 months with no symptoms or signs. However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) done at that time showed a residual intersphincteric tract with weighted score of 9 (as per Garg scoring system). The patient was informed about the possibility of recurrence. The patient presented again 20 months after the operation with a large posterior horseshoe abscess. (A) Axial section (schematic diagram). (B) Coronal section (schematic diagram). (C) Preoperative axial T2-weighted MRI showing posterior horseshoe fistula tract. (D) Sketch of Fig. 2C highlighting posterior horseshoe fistula tract in green color. (E) Preoperative axial STIR MRI showing posterior horseshoe fistula tract. (F) Postoperative 3-month axial T2-weighted MRI showing residual intersphincteric fistula tract. (G) Sketch of Fig. 3F showing residual intersphincteric fistula tract in green color. (H) Postoperative 3-month axial STIR MRI showing residual intersphincteric fistula tract. (I) Postoperative 20-month axial T2-weighted MRI showing large posterior horseshoe abscess. (J) Sketch of Fig. 2I showing large posterior horseshoe abscess in green color. (K) Postoperative 20-month axial STIR MRI showing large posterior horseshoe abscess. Yellow arrows indicate fistula location. STIR, short tau inversion recovery.

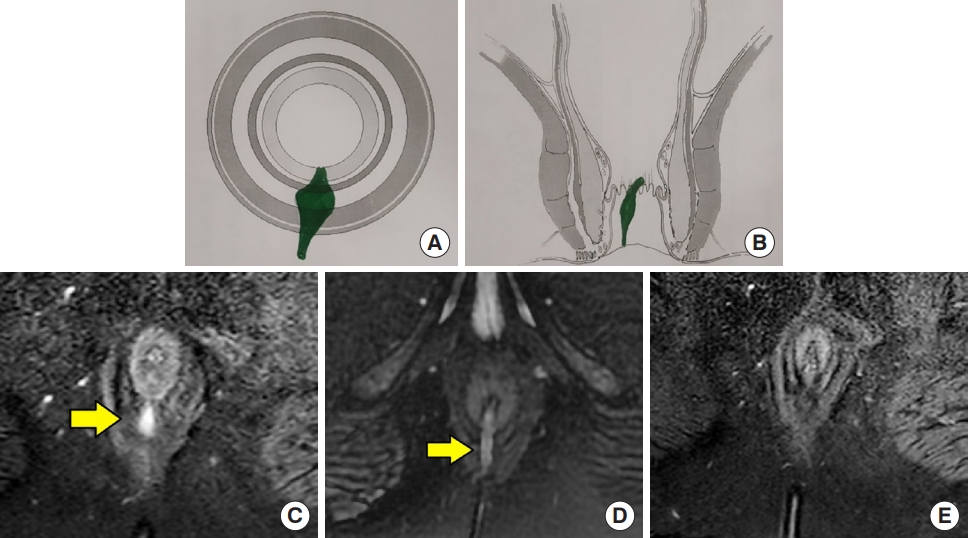

Fig. 3.

A 33-year-old male patient was operated for a right posterior small intersphincteric abscess and fistula. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) done at 3 months after surgery showed a residual intersphincteric tract with weighted score of 10 (as per Garg scoring system). The patient was followed up. At postoperative 12 months, the fistula healed completely clinically as well as on MRI. (A) Axial section (schematic diagram). (B) Coronal section (schematic diagram). (C) Preoperative axial STIR MRI showing right posterior intersphincteric fistula. (D) Postoperative 3-month axial STIR MRI showing residual intersphincteric fistula tract. (E) Postoperative 12-month axial STIR MRI showing complete fistula healing. Yellow arrows indicate fistula location. STIR, short tau inversion recovery.

Table 1.

Garg scoring system to predict long-term anal fistula healing

Total weighted score of <8 indicates healing; total weighted score of ≥8 indicates non-healing.

Reused from Garg et al. [5] according to the Creative Commons License of Dovepress’ open access publishing.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics

| Parameter | Data |

|---|---|

| No. of patients | 50 |

| Follow-up (mo) | 17 (12–20) |

| Age (yr) | 41.2 ± 12.4 |

| Sex, male:female | 46:4 |

| Recurrent | 28 (56.0) |

| Abscess | 15 (30.0) |

| Multiple tracts | 48 (96.0) |

| Horseshoe | 20 (40.0) |

| Supralevator | 8 (16.0) |

| Suprasphincteric | 5 (10.0) |

| Simple fistulas (lower gradesa) | 3 (6.0) |

| Complex fistulas (higher gradesb) | 47 (94.0) |

Table 3.

Accuracy of scoring system in predicting long-term healing

Table 4.

Weighted scores in each group

| Score | True positivea (n=31) | False positiveb (n=0) | False negativec (n=4) | True negatived (n=15) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | 2.2 ± 2.5 | 0 | 9.6 ± 0.9 | 10.9 ± 0.5 |

| Range | 0–7 | 0 | 8–10 | 10–12 |

| Median | 2 | 0 | 10 | 10 |

Table 5.

Patients with false-negative results [scoring system at 3 months predicted non-healing of fistulas (Garg score of ≥8) but the fistulas healed nonetheless]

| Variable | Patient 1a | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr)/sex | 33/male | 52/male | 35/male | 53/male |

| Body mass index (kg//m2) | 35.8 | 31.25 | 19.53 | 25.22 |

| Fistula classification | Parks I | Parks II | Parks II | Parks III |

| SJUH II | SJUH IV | SJUH IV | SJUH V | |

| No. of tracts | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| Horseshoe | No | No | No | No |

| Suprasphincteric | No | No | No | Yes |

| Tractb | Low | High | High | High |

| Procedure | Fistulotomy | TROPIS | TROPIS | TROPIS |

| Garg scores at postoperative 3 months | 10 | 10 | 10 | 11 |

| Fistula status at postoperative 3 months | Not healed | Not healed | Not healed | Not healed |

| Final status of fistula, long-term follow-up | Healed | Healed | Healed | Healed |

| Time taken for complete fistula healing (mo) | 5 | 7 | 6 | 7 |

| Total follow-up available (mo) | 13 | 15 | 15 | 18 |

REFERENCES

1. Varsamis N, Kosmidis C, Chatzimavroudis G, Sapalidis K, Efthymiadis C, Kiouti FA, et al. Perianal fistulas: a review with emphasis on preoperative imaging. Adv Med Sci 2022;67:114–22.

2. Loder PB, Zahid A. Immediate treatment of anal fistula presenting with acute abscess: is it time to revisit? Dis Colon Rectum 2021;64:371–2.

4. Garg P, Yagnik VD, Kaur B, Menon GR, Dawka S. Role of MRI to confirm healing in complex high cryptoglandular anal fistulas: long-term follow-up of 151 cases. Colorectal Dis 2021;23:2447–55.

5. Garg P, Yagnik VD, Dawka S, Kaur B, Menon GR. A novel MRI and clinical-based scoring system to assess post-surgery healing and to predict long-term healing in cryptoglandular anal fistulas. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 2022;15:27–40.

7. Jayne DG, Scholefield J, Tolan D, Gray R, Senapati A, Hulme CT, et al. A multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of the surgisis anal fistula plug versus surgeon’s preference for transsphincteric fistula-in-ano: the FIAT Trial. Ann Surg 2021;273:433–41.

8. Williams G, Williams A, Tozer P, Phillips R, Ahmad A, Jayne D, et al. The treatment of anal fistula: second ACPGBI Position Statement - 2018. Colorectal Dis 2018;20 Suppl 3:5–31.

9. Garg P, Kaur B, Yagnik VD, Dawka S, Menon GR. Guidelines on postoperative magnetic resonance imaging in patients operated for cryptoglandular anal fistula: experience from 2404 scans. World J Gastroenterol 2021;27:5460–73.

10. Garg P, Kaur B, Menon GR. Transanal opening of the intersphincteric space: a novel sphincter-sparing procedure to treat 325 high complex anal fistulas with long-term follow-up. Colorectal Dis 2021;23:1213–24.

11. Li YB, Chen JH, Wang MD, Fu J, Zhou BC, Li DG, et al. Transanal opening of intersphincteric space for fistula-in-ano. Am Surg 2022;88:1131–6.

12. Huang B, Wang X, Zhou D, Chen S, Li B, Wang Y, et al. Treating highly complex anal fistula with a new method of combined intraoperative endoanal ultrasonography (IOEAUS) and transanal opening of intersphincteric space (TROPIS). Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne 2021;16:697–703.

13. Meima-van Praag EM, van Rijn KL, Monraats MA, Buskens CJ, Stoker J. Magnetic resonance imaging after ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract for high perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: a retrospective cohort study. Colorectal Dis 2021;23:169–77.

14. Van Assche G, Vanbeckevoort D, Bielen D, Coremans G, Aerden I, Noman M, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the effects of infliximab on perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:332–9.

15. Samaan MA, Puylaert CA, Levesque BG, Zou GY, Stitt L, Taylor SA, et al. The development of a magnetic resonance imaging index for fistulising Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;46:516–28.

16. Hindryckx P, Jairath V, Zou G, Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Stoker J, et al. Development and validation of a magnetic resonance index for assessing fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2019;157:1233–44.

17. van Rijn KL, Lansdorp CA, Tielbeek JA, Nio CY, Buskens CJ, D’Haens GR, et al. Evaluation of the modified Van Assche index for assessing response to anti-TNF therapy with MRI in perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Clin Imaging 2020;59:179–87.

18. García-Granero A, Sancho-Muriel J, Sánchez-Guillén L, Alvarez Sarrado E, Fletcher-Sanfeliu D, Frasson M, et al. Simulation of supralevator abscesses and complex fistulas in cadavers: pelvic dissemination and drainage routes. Dis Colon Rectum 2018;61:1102–7.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 4 Crossref

- Scopus

- 1,709 View

- 55 Download

- Related articles in ACP